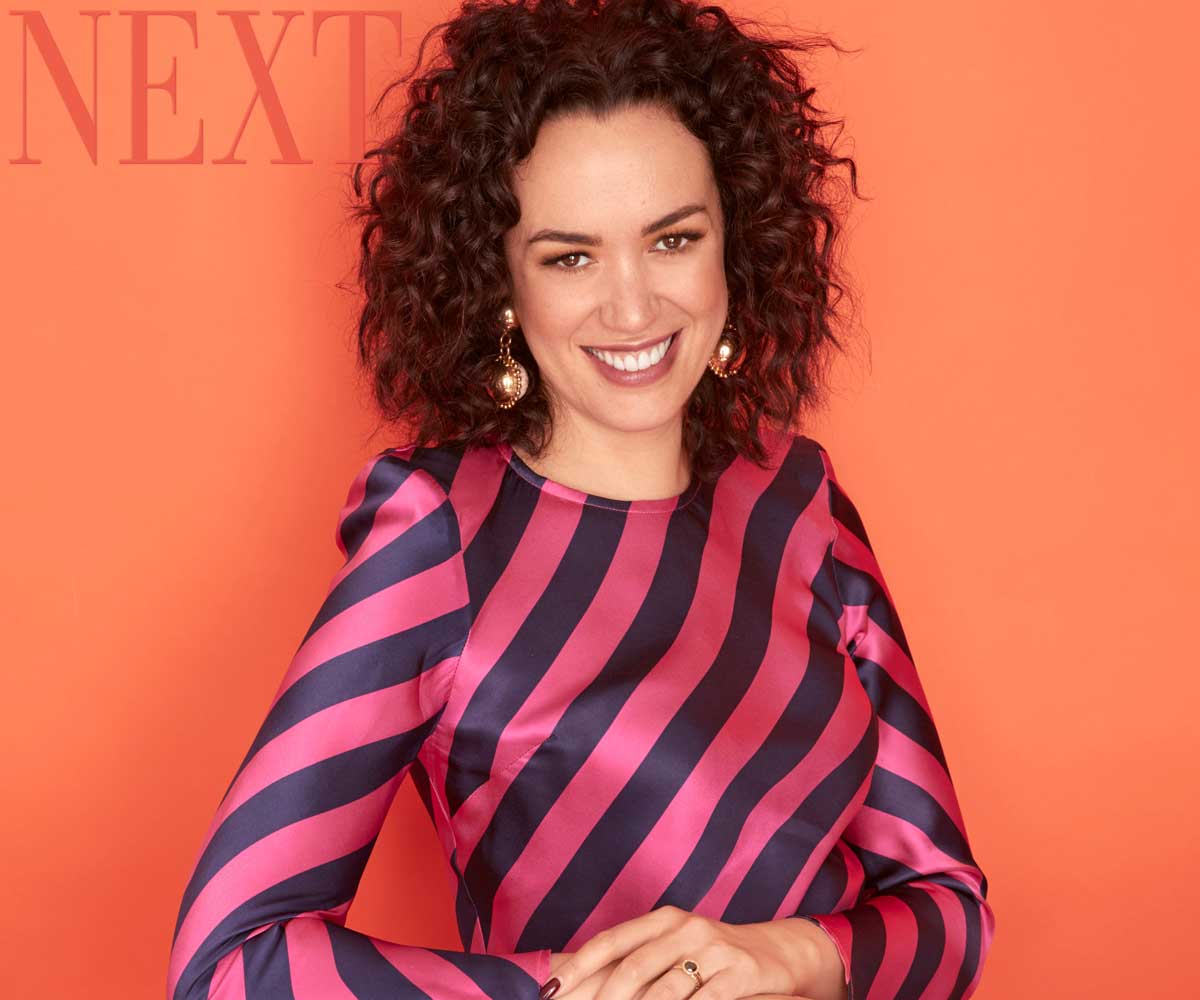

Kanoa Lloyd looked fierce in every frame. Our May cover star-in-waiting, the 31-year-old co-host of Three’s 7pm current affairs show The Project was splashed across several mock-ups on our creative director’s computer screen, channelling her unique brand of personality and professionalism in pink and purple Maggie Marilyn stripes.

This cover story – focused around her personal struggles with anxiety and her advocacy for Māori representation in the media – was well underway, filled with insights about mental health, and how inclusivity and diversity on our television screens is something all Kiwis stand to gain from.

And then on March 15 the Christchurch mosque attacks happened, and the quotes from our interview back in December took on a new resonance.

I spoke to Kanoa the following week. No stranger to adapting to breaking news, she explained that she’d been in the makeup chair at the time, preparing for that evening’s episode of The Project. A crew member ran into the room and said there’d been a shooting.

“Then he mentioned that it was at a mosque,” she says, “and my heart just sank, because you can’t hear those words without knowing that it’s a hate crime.”

Immediately reaching for her phone to read the updates that were starting to filter through online, she apologetically informed the makeup artist that she had five minutes left to finish a job that usually takes 45 minutes, and then she was out of the chair and into the newsroom, where she and her colleagues began making calls, watching coverage, and building from scratch a completely revised show that would be broadcast live on air just a few hours later.

At 7pm that night, Kanoa and her co-hosts Jesse Mulligan and Jeremy Corbett were behind the desk as planned, but there was none of the usual laughter. No studio audience, no smiles, and none of the sparkly clothing and bright lipstick that Kanoa had previously described to me as necessary elements of her “game face”.

Barely made-up and dressed in black, she began by repeating the words fresh from the lips of Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern – that they, the victims, are us. And then over the course of the next hour, the team and their guest panellists – who included a specialist in Islamic Studies, former presidents of both the Islamic and Pakistan Associations of New Zealand, and a former consultant to the US Secretary of Defense – attempted to make sense of the atrocities that had just occurred, and of the information being drip-fed from live crosses to the scene, and to the Beehive.

“I am really proud of that show,” says Kanoa, explaining that the team’s ability to implement such quick changes came down to three things – dedication, the pure adrenaline on which they were operating, and above all else, a shared motivation to do justice to the victims.

“These are real people we’re talking about,” she says. “Fifty dead, 48 still recovering from injuries. Your focus is on them and their families, and that’s what pushes you to keep going, to keep figuring it out, to keep telling their stories.”

The next day, Kanoa was in Christchurch where she and a satellite crew would spend the week doing exactly that. And as the immediate shock and horror of the event gave way to a grief that was felt around the world, she shared in the collective soul-searching of an entire nation, questioning how this could have happened in our own backyard.

“For some people, that would have meant meeting up with their friends and neighbours at their church or their pub to support one another and try to work through those things together,” she said. “We were having the same conversations; they were just playing out on TV.”

Kanoa’s focus became keeping those important conversations in the spotlight.

Sparking controversy

Kanoa has a history of using her voice for others. Getting her start on children’s television show Squirt when she was still a Dunedin high school student, the East Coast-born, qualified massage therapist of Ngati Porou descent continued down the kids’ TV route in her twenties, co-hosting after-school favourite, Sticky TV alongside Sam Wallace and Walter Neilands.

A stint at music channel C4 followed, but it was her next role as weather presenter for Newshub (previously 3 News) that really put her on the map.

In a move that foretold the courage of conviction she’s since become well-known for, Kanoa sparked controversy in 2015 when she began substituting English phrases and place names with te reo Māori alternatives.

It drew the ire of a number of viewers for whom “odd Māori words” (‘Aotearoa’ included) were an unwelcome addition to the nightly weather report.

Owning her identity

At the time, she did what any hot-headed, 20-something would do and took her anger and frustration to Twitter, where she called out the racist attitudes bubbling just beneath the surface of New Zealand’s viewing public. Messages of support came through immediately – albeit straight from the Twitter echo chamber – but then the story was picked up by national and international media, and a wider New Zealand audience was forced to do a bit of self-reflection.

Looking back, she says this wasn’t her intention – she was just trying to make her segment more interesting.

“And I honestly didn’t think what I was doing was that outrageous!” she laughs.

As for going in to bat for herself on social media, “It was terrifying, but the fear lost out to this searing hot anger I had over being told by strangers to shut up.”

For the way they handled the whole situation, she acknowledges her MediaWorks bosses, who had her back from day one. “I remember being called into this nerve-wracking meeting and thinking I was about to get in a lot of trouble, but instead they were like, ‘Are you okay? What do you need? How can we support you?’ I imagine there are plenty of companies where I’d have been left to flounder and figure it out myself, so to have been so well looked after just made me think, ‘I’m home.'”

While she says she “doesn’t blow so hot on social media any more”, she continues to advocate for te reo usage both on screen and as an ambassador for Māori Language Week.

She’s adamant that she’s not doing it out of obligation. “I think people are only going to connect with you if you’re being authentically yourself, so if you shoulder it as this job you’ve got to do, then what you’re saying will never land.”

If anything, she says she’s figuring out her own identity and her relationship to her culture at the same time as everyone else, “I just have an epic platform on which to do it, with really clever graphic designers who make everything look cool.”

Digging deeper

Pre-March 15, Kanoa spoke with pride about The Project‘s diverse selection of stories and guest panellists, and the effort that went into ensuring all New Zealanders felt represented on and by the show.

“We do feel this collective responsibility to produce something that looks like what New Zealand looks like,” she’d told me. “We’re definitely not perfect,but we try to include a mixture of faces and perspectives each night, including ones that look and sound like mine.”

Post-March 15, the team, according to Kanoa, realised how much more work had to be done.

“I think there will be a lot of people – myself included – who’ve been shaken out of their bubble by this, and who are now looking around and going, ‘Okay, what other groups of people are missing from this equation?’ What do we know about our Sikh community, or, do we spend enough time telling stories about our elderly?’

All these marginalised groups that you know exist, and that you feel like you’re around all the time, when it comes down to it, are they visible enough?”

Kanoa says all of those questions are currently being asked at The Project. “We’ll be answering them honestly, and working to make improvements,” she says. “And then it’s up to the viewers to vote with their remote.”

Explaining that there’s an onus on Kiwi audiences to pick up what shows like The Project are putting down, Kanoa says that the team can’t control what people respond to. “We can’t force anyone’s hand. But we can keep making content that we think is good, and trust that they will engage with it.”

A content piece that audiences engaged with in 2018 related to something very close to home for Kanoa. “We were doing a themed week specifically around anxiety, just because the numbers are so high here. Something like one in four New Zealanders will be affected by it at some stage, so we wanted to connect with people over that.”

She hadn’t planned to share her own experiences with the mental disorder, but says she ended up writing a little piece and showing it to her boss, who encouraged her to read it on air. “Basically I said, ‘I have anxiety’, and then I talked about the ways it manifests for me, including that my hands and feet go numb, which I’ve since realised is because I’m hyperventilating.”

Describing this symptom as “a physical reaction to internal stress”, Kanoa says parties and other social events used to be especially triggering for her due to the prospect of being judged.

“Even going to the supermarket sent me into a spin because I thought, ‘What if I run into someone I know and I’ve got a horrible outfit on?'”

She says admitting to such thoughts on live TV felt like a big deal at the time, but by that point she knew they were incredibly common, and she wanted to make others feel less alone.

Well and good

As far as managing her anxiety, therapy has been a game-changer for Kanoa.

It took her a few appointments to find someone she clicked with (crucial to making it work, she says), but now that she’s met ‘the one’, there’s no going back.

“We do a lot of goal-setting and debriefing about the things that stress me out,” says Kanoa, who explains that far from lying on the sofa and talking about her childhood, her therapy sessions are incredibly practical.

“If there’s something in my life that I don’t know how to approach, she’ll help me figure out whether I’m putting it off because I don’t want to do it, or because I’m a little bit fearful, and if that’s the case we just acknowledge that I’m having a little anxiety flutter and after that I can tell myself, ‘Actually, I’m fine. I can do this.'”

Kanoa’s friends – many of whom she’s converted to therapy – are now willing participants in day-to-day mental health chat, and she thinks this is indicative of a nationwide shift that’s seen it become an increasingly acceptable topic of conversation.

“I sometimes joke with my girlfriends that all we talk about nowadays is boys, babies and our brains. And if you’re doing that over a bottle of rosé on a Friday night, it’s definitely part of the national psyche, right?”

Although encouraged by the direction things are going in, and “cautiously optimistic” about the moves the government is making to put an ambulance at the top of the anxiety and depression cliff, Kanoa says that our discussions need to extend to “decidedly less chic” disorders, such as schizophrenia and psychosis, if we are to have any hope of addressing New Zealand’s woeful suicide statistics.

“The conversations that we’re having now are just the tip of the iceberg,” she says. “But it’s the start of something, and hopefully of more people seeking help.”

In addition to therapy, a number of recent lifestyle changes have made it easier for Kanoa to keep her anxiety in check. A loosely-keto, lower-carb diet that she adopted in September opened her eyes to the things she was consuming that her body did and didn’t agree with. While she’s not as strict on herself now, she says the experiment set her up for better habits, and she’s convinced these have made her sharper and more energised.

“If someone offered me a cracker I wouldn’t smash it out of their hand,” she laughs when asked if the slice of cheese on a cucumber she once vouched for as a favourite snack would really satisfy her. “But I have noticed that I feel really bad if I do fall off the wagon.”

After hosting last year’s Vodafone New Zealand Music Awards, the temptation to treat herself to a beautiful dessert got the better of her. “The next day I felt hungover, like I’d punched a whole bottle of wine,” she recalls.

“I felt anxious and nauseous and I had a horrible headache.” A nail in the coffin of what she calls “mindless eating”, Kanoa says it’s not like she’ll never let loose at a party again. “But I have to plan for it, and know that I might feel a bit awful afterwards. And I’m starting to find that it’s easier to just go without.”

Open and honest

Walks on the beach with her dog, Brown, are another must whether she’s at her best or her worst. And then there’s her husband of two years, production company owner Mikee Carpinter, with whom she’s devised gentle code language to keep communication flowing throughout the rough patches.

“One of the first things I learned in therapy was that I wasn’t actually talking to him very much about how I was feeling. So I would start feeling down, not say anything, and then suddenly explode about the laundry or something. And I don’t think of myself as an angry person or someone who gets upset about nothing much, so being able to figure out ways of identifying that I am perhaps in a bit of an anxious state has been massively helpful for us.”

Kanoa says the question “How’s your patience?” is Mikee’s way of checking in on his wife’s mood. “And I’m allowed to say ‘It’s bad,'” she says.

“We will leave it at that for a bit and I might take the dog to the beach or the park, because he doesn’t care if I have bad patience.”

Other times she’ll ask Mikee for a ‘wrap-around cuddle’, “which is when I just stand there like a lamppost and he wraps both his arms around me and I can just be still and not have to say or do anything.”

Here to help

On how friends and family members of anxiety-sufferers can show support for their loved ones, she says that “just being there” is number one.

“This rule is really hard for me to abide by because I’m such a doer,” she says. “But try not to offer up a solution or advice or a way to ‘fix’ things. You want to help so you might think ‘I’ll get you a cup of tea, then I’ll put you to bed, and then tomorrow I’ll take you to this appointment and it’ll all be okay’, but that’s actually the last thing that someone in a crisis needs.” Instead, she suggests quietly comforting gestures like sitting with your loved one, holding their hand, looking them in the eye and listening.

“And be ready for when the clouds part, because they do, and all of a sudden this person that you maybe haven’t seen or heard from for a while is going to be like, ‘Hey! I’ve really missed you.’ If you’re able to identify that they’ve had a hard time and not be resentful or mistrusting when they reach out, that can make such a big diffrence.”

Now more than ever, solidarity is what will get us through, and Kanoa stresses that if a loved one is withdrawing, don’t give up on them.

“Keep inviting them out,” she says. “Because I know from experience that even if they said ‘no’ the last seven hundred thousand and one times, it’ll be on the seven hundred thousand and second time that they say, ‘yes’. They do still love you, I promise.”