It wouldn’t be amiss to say that Ivan Pivac is an accomplished man.

He was one of the earliest Kiwi acupuncturists to practise in New Zealand; he holds degrees in Spanish, psychology, economic history and business studies; and formed a company that imported products for special needs clients.

It’s an impressive list of achievements made all the more inspiring by the fact that Ivan is legally blind.

“The philosophy I adopted early in life is not, ‘What if?’ − that’s not in my vocabulary − it’s more, ‘Why not?’ Because if you want to do it, then why not give it a go,” Ivan tells.

“You know your limitations and that’s really important. I know what I can do and what I can’t.”

Ivan believes being legally blind actually makes him the perfect acupuncturist.

Ivan’s eternally optimistic attitude has seen him overcome hurdles that could have stopped others in their tracks.

When he talks about his lack of sight there is never a hint of negativity or sadness.

In fact, Ivan believes that he is at an advantage over those who have full sight.

“Now, there’s a new way of describing it − one is not blind, or visually impaired, you are light dependent,” he says, smiling.

“People who are light dependent obviously have a handicap so, when you think about it, I’m not dependent on light, I’m totally independent.”

But the scholar has not been blind for his entire life, sharing how he was the victim of two freak accidents that robbed him of his sight before he reached adolescence.

At the age of six, Ivan’s vision in his right eye was compromised after a knock to the head and then, tragically, at age 12, the vision in his left eye was damaged after being hit by a tennis ball.

Within a week he and his family noticed significant deterioration and ultimately Ivan completely lost his ability to see.

“If you’re going to lose your sight I always say to people that the age of 12 is really a great time [for it to happen],” he reflects.

“The reason basically is that you’ve gone through childhood and developed a lot of visual memory, you know a lot about colours, shapes and movement and that’s all very firmly fixed in one’s mind.”

Ivan reckons that being young also made it much easier to pick up new skills such as Braille, which he quickly mastered at an Auckland school for the blind.

Despite the alphabet for the visually impaired being developed in the early 1820s, when it came time for Ivan to study there weren’t many resources or textbooks available for him to use.

Instead, Ivan’s mother, Frances, would read to him, letter by letter, while he rewrote it all in the touch-sensitive script.

Ivan’s interest in anatomy saw the physiotherapy graduate head to Hong Kong to study acupuncture in 1974 after witnessing great success using the ancient treatment while working in London hospitals.

“I had a feeling right then and there that they actually didn’t expect a blind person to turn up, even though I had told them [I would],” he laughs.

Although Ivan explains that it’s not uncommon for sight-impaired people in the East to take up the occupation, he believes he may well be one of only a few in the Western world.

“Even today 45 years later, I have still not met another blind acupuncturist.”

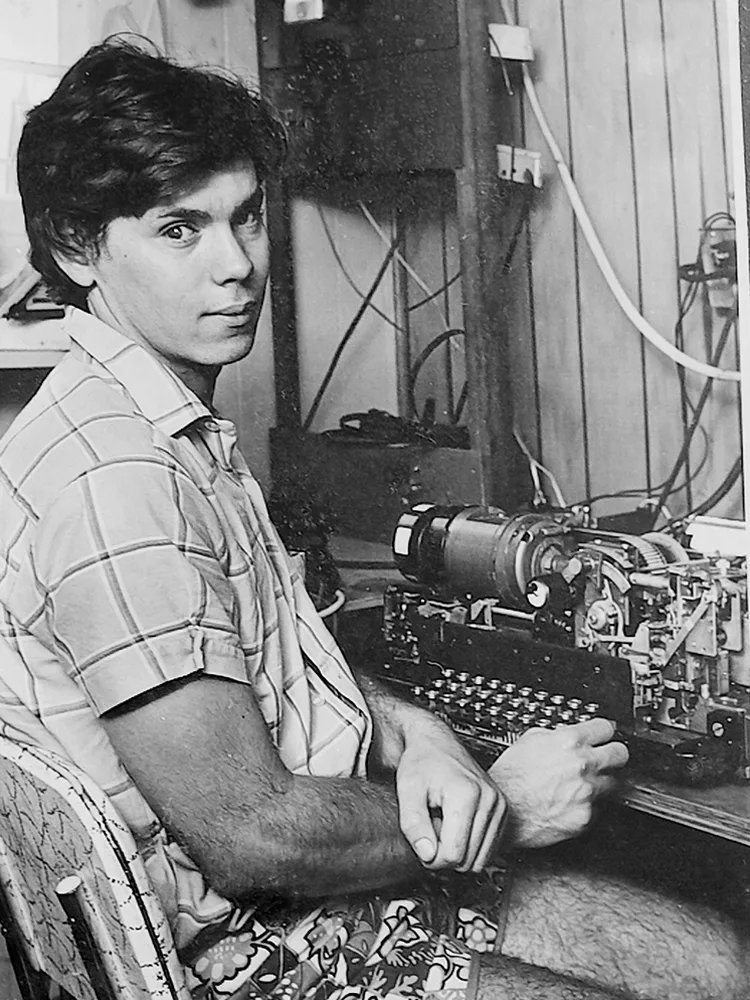

Along with his many academic achievements, Ivan is also a HAM radio enthusiast (below in 1974).

They say when someone loses one of their senses others are heightened, giving them the ability to pick up on things the average person can’t.

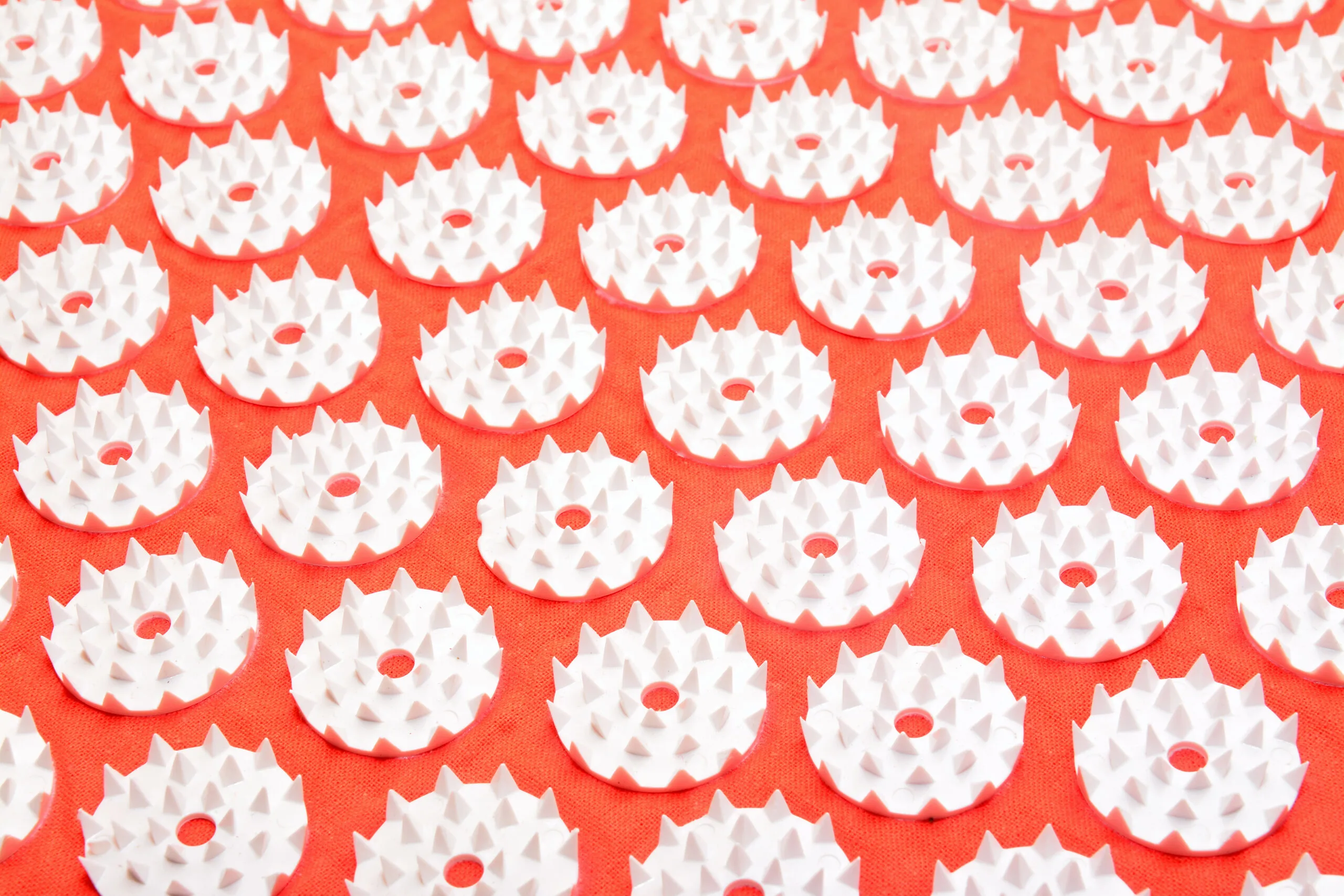

This is perhaps why Ivan makes the perfect acupuncturist.

“My sense of touch is very good, so for me I really have an advantage over somebody who can see.

“When you’re locating a point there’s a lot of surface markings, so for a blind person being able to feel these bumps and depressions and bony points is really quite easy,” he explains.

Beloved by his clients, the 70-year-old has been practising in the same clinic, below his home, for more than four decades and shares that he is now treating third generations of the same families, tending to up to 500 patients a year.

He says the best part of his job is interacting with clients.

“The people who come and see me aren’t typically what you call patients, they’re sort of like friends. You’re just helping someone out and they go away with a smile on their face,” he says.

“The secret is really listening to what people have to tell you.

“People ask me how much longer I’m going to work and the answer is I really don’t know. As long as the phone keeps ringing, I’ll keep working. If it stops obviously I have done my job.”