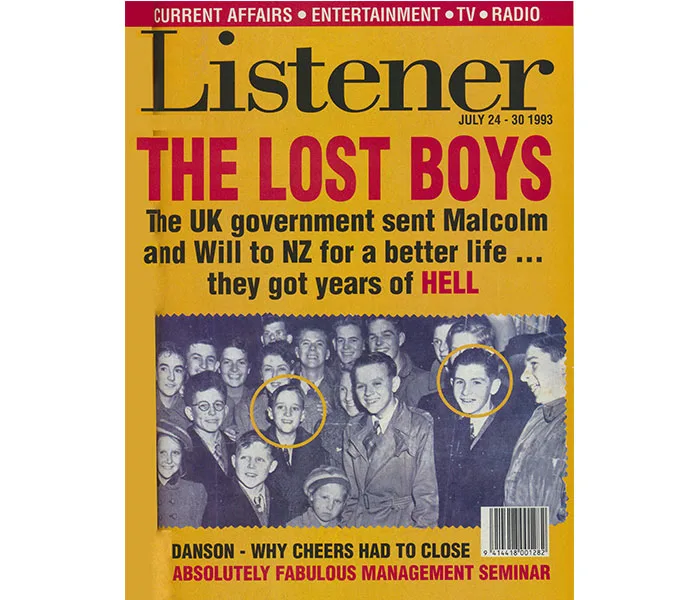

From the New Zealand Listener archives

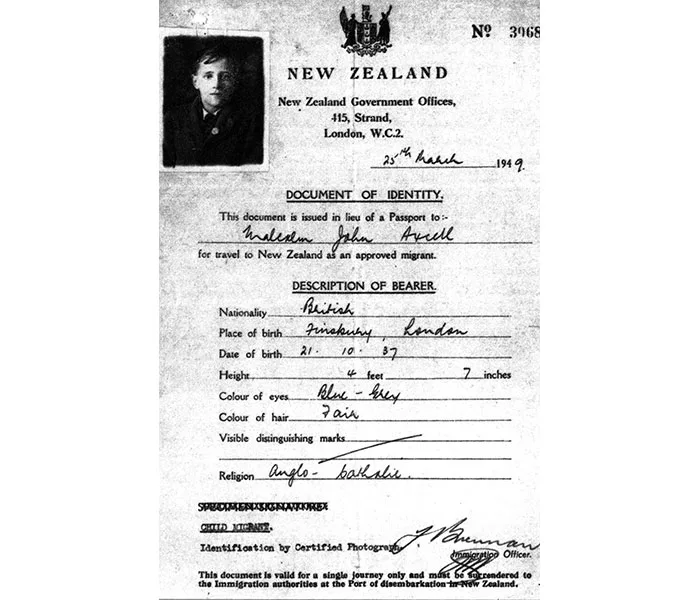

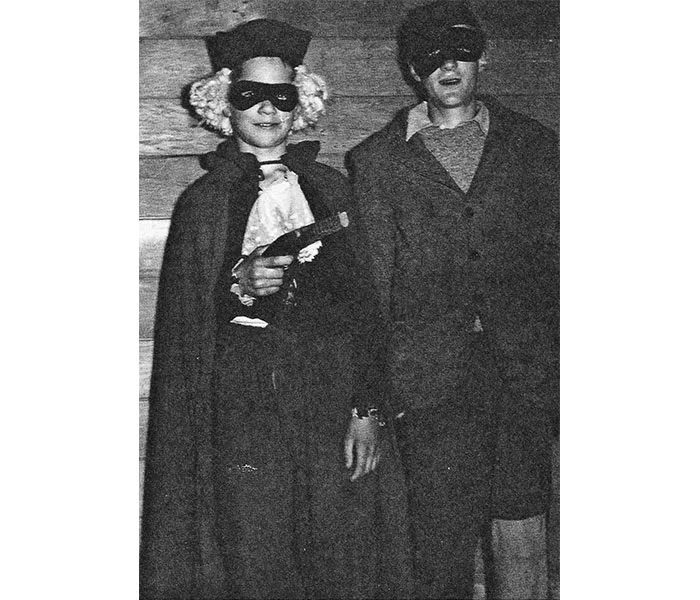

When 11-year-old Malcolm Axcell boarded the Rimutaka for New Zealand in early 1949, it was the beginning of a long, sad odyssey. This boy was to be the first of 600 child migrants to step ashore in New Zealand in the post-war years.

He had been sent far from his war-tom and poverty-stricken family in London – his “stepfather” had lost a leg in the war – to a new life in what a New Zealand newspaper article described in glowing terms as the “space and fresh air” of his aunt and uncle’s state house in Meadowbank. Such was the belief in the ennobling power of hard work in the colonies that Malcolm was seen as lucky to have the opportunity to scrub out the washhouse and dig the garden, as he had done the day the reporter visited.

But what nobody noticed was just how much work the boy was made to do. And what nobody asked was how a couple who had been reported to Child Welfare the year before for keeping an 18-month-old foster child tethered to a post in the garden and who had been judged “not satisfactory” as foster parents could be allowed to take Malcolm in a government-sponsored scheme simply because he was a relative.

“All of a sudden,” says Axcell, “I was their slave. They had a new state house and the grass around it was waist high. It was my job to dig that quarter acre. I wasn’t allowed to go out and play after school or at weekends. I had to get them breakfast in the morning, wash the dishes, sweep the floors, clean the house and get the section dug.

“Imagine,” he says, “bringing a child in from Somalia, and putting him to work doing heavy digging all day. Nutritionally those kids are history, and people say it just couldn’t happen here. But it did happen. It happened to me.”

At 11, Axcell was just six stone (38kg). Child Welfare officers noted him as being “anorexic” and suffering from “numerous colds and general malaise”. He was so unwell he couldn’t attend school for the first two months in New Zealand; years later his constitution was still described by welfare officers as “frail”.

But right from the start his aunt and uncle made it clear that he was there only to work.

“It was like being in a strict camp. I had to knock before I entered the lounge. They wouldn’t speak to me, they’d just give me orders about what to do. If I didn’t do it properly, or the way they wanted it done, I’d be hurled out of bed and made to do it again.”

Malcolm Axcell is one of the “Lost Children of the Empire”, Britain’s unwanted who were sent to the ends of the earth. From the 17th century to, astoundingly, as recently as the early 60s, 180,000 disadvantaged children were shipped off to the colonies; a fact seemingly forgotten until 1987 when British social worker Margaret Humphreys began to uncover stories of the “horrendous abuse” suffered in institutions by many of the 10,000 children sent to Australia after the last war.

Their experiences were dramatized in The Leaving of Liverpool, a television series that screened in New Zealand in 1993. At the time, Humphreys believed it would “lift the lid off” the treatment of child migrants who came to New Zealand under “this callous policy of exporting children”.

In New Zealand, says Dr Dugald McDonald, senior lecturer in Social Work at Canterbury University, the child imports started with the boy convicts of 1842 and ended only in 1954. By taking these children – as young as five, but usually in their teens – New Zealand was doing its “patriotic duty” in helping Britain out. “But the aim was also,” he says, “to populate the empire with ‘good British stock’.”

Only now are many of the child migrants to the colonies able to find their families again: the Child Migrant Trust set up by Humphreys receives hundreds of calls a month from migrants who were told they were orphans while their mothers in England were told they were dead. Increasingly, Humphreys gets calls from New Zealand; from “people who’ve been holding the hurt inside for too long now”.

As a young child migrant, Malcolm Axcell considered running away.

“But where to? I had no money. I didn’t know anyone. I just used to cry in bed at night, you know, for Mummy. But it didn’t help.

“I idolised my mother. Before I left London, I used to buy her little bunches of flowers with the money I’d got from working in a butcher’s shop on Saturday mornings. And all I kept thinking about was, ‘What did I do wrong, that she sent me to New Zealand?’ If it was because they couldn’t afford to keep me, why did she have another baby less than a year after I left?”

Axcell was to learn from his aunt and uncle the bewildering information that he had been illegitimate. And he could remember being “belted up” by his stepfather, and other attempted abuse.

It had been recommended by the inspector of the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children that this “well mannered” boy, so “alert and willing to learn”, would have a better future in New Zealand. But still the 11-year old, who till then had been called Malcolm Barker, couldn’t accept that his mother had changed his name – “just as I got off the train to go on the boat she gave me a piece of paper with my new name, her maiden name, which I couldn’t even pronounce” – and sent him away.

“Even now it just bums me up.”

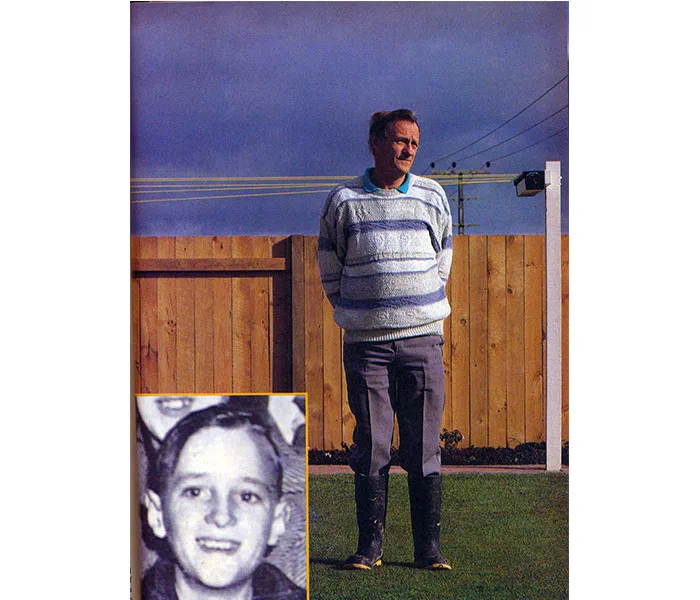

Axcell sits very still, holding his folder of precious identity documents as he talks. But his words pace up and down, up and down, like prisoners in a cage.

“I always felt as though I was trapped; that they’d put me in a deep hole and I could never get out of it. If they’d just listened when I tried to tell them that I’d be better off back home, then maybe things would have been different.”

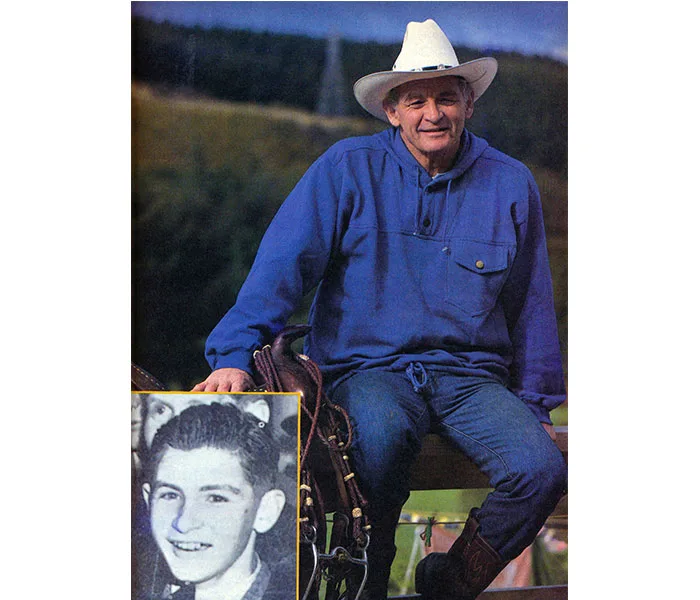

Malcolm Axcell

But nothing changed.

“I knew within three months that they [his aunt and uncle] didn’t want to keep me. But the thing is, they couldn’t get rid of me.”

Why? The government had legal guardianship. But the record shows: “On the superintendent’s direction, they [the aunt and uncle] were informed that they had nominated him and they must keep him.” The problem was just assumed to be with the boy. A comment from head office said that “the boy would probably do with a good talking to”.

The superintendent scribbled on a note that “apparently he wants ‘a little straightening up’”.

But when the Boys Welfare Officer investigated, he found that any misdemeanours the aunt and uncle had complained of “do not seem to be worth all the fuss…” They included such things as leaving dirty fingermarks on the wall. Yet the boy was threatened with severe punishment: the welfare officer reported that “Malcolm has been very good for the last few days, since my last visit, when [the uncle] told him that I said if he didn’t behave himself he would have to go to a Home.”

The school reported that they had not had any trouble with the behaviour of this “bright, friendly lad”, although he was held back a class because of his interrupted schooling. Yet even Child Welfare were beginning to worry.

One welfare officer reported: “I was rather disturbed by the way Malcolm spoke to me when I called. He seemed to accept too readily rather arbitrary restrictions on his movements and have me, parrot fashion, reasons why he should not play with other children or engage in normal boyish pursuits.”

“My uncle,” says Axcell, “used to box my ears, no harm done, but what was worse was he wouldn’t let me play with school mates.”

The welfare officer noted that as a punishment Malcolm had been prevented even from joining one of the division’s own outings “for some very petty reason.”

Then, in July 1950, a neighbour called at the Child Welfare office and said “she was worried about a little British boy living near her”.

The statement noted: “There is little affection shown towards this boy” … all orders and words addressed to him are spoken in a cold manner. Recently [the aunt and uncle] went to Hamilton for the weekend and left 12-year-old Malcolm home to feed the dog and cats.”

The neighbour gave him meals. This woman was worried about the regimentation; about his health – “he has sores on his feet” – and about the fact that the boy was “repressed” and upset by the way his aunt and uncle spoke badly of his mother.

In August the welfare officer reported “alarming developments”. Malcolm’s mother, worried about his happiness, had written to him asking if he wanted to go home. And he did. He desperately did. He told the officer “he has had a worse time in this country than he had in any of the homes or foster homes he was in in England and that he wants the return there; he is unhappy with his uncle and aunt, who he thinks are quite unreasonable and do not want him”.

The officer, no doubt aware of what an embarrassment it would have been for the New Zealand government to send a child back from this “better life” in the Dominion, was quick to point out “I want to make it quite clear here that in all my dealings with the boy, and particularly on this occasion, I have been intentionally off-hand with him and have not given him any encouragement to make any complaints…” and nothing came of the attempt to get Malcolm home.

The boy understood the rules. “You weren’t allowed to say you didn’t like it here,” says Axcell.

As another Boys Welfare Officer was to note in October that year: “He admitted that he was not happy, missed his mother, but had no word of condemnation to say about either [his aunt or uncle]. In fact, he admitted that he was to blame for the unhappiness which had been caused in the home.”

But in August the Child Welfare office received another “alarming” complaint from a “scrupulously fair” neighbour. This man informed them “that the whole street is very much concerned at the treatment meted out to Malcolm, who is generally regarded as a slavey or flunky” for his aunt and uncle. The neighbour said that he got up to go to work at 5.00am.

Malcolm’s aunt could be seen in bed through the blindless windows, while the uncle shaved and Malcolm was at this time preparing the breakfast, which he took in to his aunt. The neighbour would then see him washing the dishes at 5.20am and often saw him shaking the mats outside the front door at 6.30am when the neighbour left for work.

“Malcolm frequently works all day Saturdays on heavy work such as chopping wood, for which his physique is hardly suited, not to mention the loss of normal recreational activity. While he is doing his work [the uncle] is quite likely to be shooting at birds from a window, meanwhile shouting instructions to the boy, or else to be fishing for small fish for cat food in the stream.”

The neighbour told the welfare officer that “the fairly large backyard was a wilderness before Malcolm came but it is now looking a good deal better – due almost entirely to Malcolm’s unremitting labour. The boy is prevented from forming normal associations with other local boys and is treated as a stranger in the house. He is not allowed to go to bed until he has completed his quota of jobs” – a quota which the neighbour described as “out of all reason” – and is “deprived of any small pleasure at the slightest provocation”.

In September the neighbour put it in writing, concluding: “The boy has a good name in the street for conduct, but his health appears to be very much below standard.”

And still it went on. On October 18 the Child Welfare officer noted that Malcolm was no longer getting pocket money: the aunt “made it quite plain that she and her husband are not prepared to make any sacrifice, financial or otherwise for him…” Malcolm had to earn the money to pay for glasses ordered by the school medical officer.

By November the Boys Welfare Officer was convinced Malcolm would be better off in a boys’ home. But the memo came back from Wellington: “The admission of this lad to the Boys Home cannot be approved, as this would not be in accord with the [Child Migrant] scheme.” The promise to the British government and to the children’s parents was that child migrants would only go to private homes.

There was another problem. The New Zealand government was not prepared to pay any board for these children, other than the 10 shillings a week child benefit, to foster parents. The Child Welfare division advertised in the newspapers for someone to take Malcolm free of charge. Nobody wanted him.

A note from the welfare officer dated December 5, 1950, says: “Not having any news to tell [the aunt and uncle], I have studiously avoided visiting the home … ” The welfare officers were in a trap. But they left the boy in a worse trap.

Malcolm Axcell has “blocked out” any memories of his last months at his aunt and uncle’s. But just before Christmas the first neighbour “called at the office to find out whether something could not be done to remove Malcolm from his uncle’s care very soon”. The neighbourhood was concerned at Child Welfare’s “deaf ears” stance. This woman “was most upset and gave a number of instances – of recent date – of unkind treatment: he was sent to collect pine cones while [the aunt and uncle] went to the pictures; he was given only two or three sweets of a large quantity given to the family expressly for the boy… There was a long list of a small child’s misery.

The other neighbour had now reported giving the boy some of his own clothes, since he appeared not to have enough. But within a day or two the neighbour had seen the uncle wearing them. This man also considered “that the boy is not properly fed; he says the family’s meagre supply of milk has not increased since Malcolm arrived, that on the few occasions he has given Malcolm a meal, the boy has eaten quite ravenously and that he has heard [the aunt] tell Malcolm he is eating too much”. Child Welfare officers themselves later noted that Malcolm “looked like he could do with a good meal”.

By this time head office had decided that Malcolm was only “15 percent” to blame for his own unhappiness. Efforts were made further afield to find him free board. He was finally taken in June 1951 by a farmer near Palmerston North. As Dugald McDonald pointed out, “unfortunately a number of the placements were with farmers wanting an extra pair of hands.

Labour was in short supply in New Zealand until the 60s and this was a way of getting workers. I think the Child Welfare division colluded in the hope that it would be a benevolent exploitation. But at the end of the day, if you were expressly forbidden to put the kids in institutions, then you just had to place them with whoever was willing to have them.”

The most damaging thing, says McDonald, is serial fostering – and that’s just what Malcolm Axcell was to experience as placement after placement broke down over the next few years.

“Each placement,” says McDonald, “reinforces the sense of worthlessness; each one is a rejection. It becomes harder and harder to establish nurturing relationships with adults.”

McDonald, who has spoken to Malcolm Axcell and other child migrants, believes that Axcell’s story of rejection and separation meant that as a teenager he was unable to make any firm emotional attachments with his foster parents/employers.

“Most pitiful of all were the sudden departures. There was no warning that he was about to be moved on, no follow up. Nothing.”

Malcolm was given basic essentials. The Child Welfare officers, in removing him from his aunt and uncle, discovered that no clothes had been purchased for him since his arrival nearly two years earlier and they had to buy shoes, pyjamas, everything.

“But I still had no control over my own life. I was told to milk cows – I’d never seen a cow before.”

He was made to do dangerous work – breaking in horses – and was often hurt, requiring hospital treatment.

Although dux of his local school, he was given no educational opportunities.

“At 13 I was working for my keep. I got up at five in the morning, went out and got the cows in, milked them, 80 of them, cleaned out the shed, put the cows out, feed out if it had to be done, got changed, walked a mile to the school bus, and then did it all again in reverse about half past seven or eight at night. Homework? What was that?”

Although in one place there was an older son of the family, Malcolm was the only one who worked on the farm.

“I can’t ever remember having a birthday present. Christmas time was the same. It wasn’t my right to expect presents. I just did as I was told. If I didn’t, it was, ‘I’ll get the Welfare man in and you’ll go to another home.”

One day Malcolm went home and told his foster father he wanted to do what the other boys at school were doing and go on to secondary school, “tech”, for two years so he could later be an apprentice. The farmer told Child Welfare he wanted Malcolm off the place “immediately”. Later when the lad told another farmer that he had signed up for the air force so he could learn a trade, the farmer “went ape and started knocking me around.”

Malcolm had always found it difficult writing to his mother “because I didn’t have any money for envelopes and stamps and didn’t even know how to get into town”. A letter his mother wrote to him in January 1952, saying she wanted to join him in New Zealand and signed “love Mummy”, was given to him only in September 1990, when he was finally given copies of the documents – including school reports, medical records, his birth certificate and entry permit – held on the Child Welfare file. But in 1954 his mother, worried about him but unable to send the fare home, sought permission for him to work his passage home. It was denied. Child Welfare told Malcolm instead, in writing, that he had “a chip on his shoulder”.

After that, he gradually lost touch with his mother. Then in 1987 his wife and son gave him a surprise trip home to England; his first in 38 years. He got off the plane in London and got a taxi to his mother’s Brixton address.

“I said to the cabbie, ‘Wait’, when we got there because I didn’t know what was going to happen. I was apprehensive as anything. I went up and knocked on the door. She opened the door and looked at me. I said, ‘Don’t you know who I am?’ and she said, ‘No. What do you want?’ I said, ‘I’m Malcolm.’ She didn’t cry. She didn’t do anything. Being so far away all that time, something had happened. I had lost my mother. I stayed a few days but there wasn’t anything left. There’s just nothing there.”

Axcell and his supportive wife, Vera, organised a reunion in 1990 of his group of 20 child migrants. Although most had been able to maintain contact with their families, three had died tragically, one of them alone and penniless in a Porirua Hospital.

Will Rogers

Will Rogers, who came out at 15 on the same ship as Axcell, knew the anguish of separation and isolation. He had been in a Liverpool orphanage since the age of four, when his father was killed in the war. His mother was already dead.

“One of the last things my father said was, ‘If anything happens to me, don’t split the children up.’ When I went to New Zealand there were promises that my brothers and sister would be able to follow. But it never happened.”

After a year at Flock House, the 16-year-old was sent to an isolated East Coast farm where he saw no one but the farmer and his wife.

“I never even met the neighbours.”

He ate in isolation: “The lady of the house would not have me at the same table.”

Before breakfast he would have to milk the cows, separate the milk, feed the horses, saddle them, and dig the vegetables that the farmer’s wife had listed on a blackboard by the back door: “She didn’t talk to me.” At night, after a day’s heavy work on the farm, he would again milk the cows and attend to the horses. Dinner he ate on his own in the kitchen, before going on his own in the dark to his whare.

“The isolation was hard, really hard. Coming from an orphanage, I’d never been on my own before.”

The only reading material he had were farming magazines. This was the young man whom a psychological assessment for a management position later described as having “an intellectual rating superior to 95 per cent of the population” and who it said “impresses immediately” with his social skills and “somewhat infectious sense of humour”.

Yet he was stuck in a place where, for him, there was not even a Christmas: “I’d spend it looking after flyblown lambs.” There were no birthday greetings, no holidays, no sick leave: in fact Rogers eventually got the sack for having flu one day and not being able to work. Having to pay for a working dog, a saddle and all his clothes from his wages, he had literally no money for stamps and envelopes, even if he could have got to town to post a letter. “The saddest thing for me was that I lost contact with all my friends in the orphanage.”

A shift to Akitio sheep station meant Rogers was able to make “lasting friends”; “I regained my self-respect”. But he questions whether anything can compensate “for the loss of family and the comradeship of my schoolfriends”.

Rogers doesn’t want to sound “like an ingrate”. Nor does Axcell. But neither is at all sure that life would have been worse back in England. When Rogers went back in ’57, his mates all had jobs and homes. “All I had was a saddle.” Both are adamant that such a policy of child migration should never be carried out again.

“Look,” says Rogers, “we’ve just seen the case of one of the Croats who couldn’t settle here even as a young adult.”

Axcell: “It’s got to stop. But they’re doing it all over again with the Romanian children. They haven’t learnt. Taking children away from their families and their culture will never work unless there is a guarantee that they can be sent back if they want it, or for their families to come and visit them. But you can’t just dump children in a strange place.”

Axcell: “It tore my life apart, being sent to New Zealand. When I went back in ’87, the tears, it was awful, not belonging there, not belonging here. I couldn’t talk to my wife for three months after I came back.”

Axcell and Rogers speak of the high emotional cost: both say they have difficulty talking to their own children.

“What you’ve been taught to do all your life,” says Axcell, “is to just walk away when things go wrong. Any conflict, whoof, you’re off. I just never learnt how to handle things.”

His two sons, he says, will read for the first time in this article of all the things he has “kept inside”.

There are other grievances: Axcell is trying to get a British passport, but refuses to pay the $57 fee.

“They took my identity papers off me when I arrived; it’s my birthright to get my passport back. Without a British passport I’m only allowed a three-month visa.”

A woman at the consul’s office once told him that he was just a “whinging Pom”. “That hurt,” says Axcell. He wishes “every success” to the Australian brother and sister who are suing the British government after being

The big question, says McDonald, who is researching child migration, “is should we ever do it again?” There are always humanitarian reasons for saying yes; always children somewhere in the world in need of care.

“But, as schemes,” says McDonald, “they’re bloody terrible.”

New Zealand, he says, was enlightened enough to decline to take Hungarian children in 1956; and is enlightened enough now to have open records and to keep to its responsibilities under the Treaty of Waitangi, the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the principles of the Children, Young Persons and their Families Act, “which makes it quite clear that our philosophy is to keep children with their families”.

“Yet,” says McDonald, “we’ve got this double standard for overseas adoption. Children can still be amputated from their culture.”

He believes that, thanks to the vigilance and caring of individual Child Welfare officers, “we didn’t do too badly” with the 600 children who came out under the Child Migration Scheme. But what’s interesting is that the most successful placements in many cases were not the homes offering social advancement to the children but the core of ordinary, caring, “grass roots” foster-mums whom the Child Welfare division called on to take the children when the planned placements broke down, as they so often did.

“The foster parents come out as the baddies,” says McDonald, “but often the reality of having, frankly, a disturbed child in the family was more than they could cope with. Those situations were doomed to fail.” Although there were also many “good fits”, McDonald has come across a lot of former child migrants who are now “very troubled individuals”.

Many, like Malcolm Axcell, feel there must have been something wrong with them to have been sent away, and suffer feelings of unresolved guilt and rejection anguish.

“There is a generalisation coming through now quite clearly,” says McDonald, “that the separation trauma and adjustment problems are worse the younger the child – and I’ve found children who came out as young as seven.”

There’s also a gender issue: “It was okay for the girls to be nurtured and vulnerable, but with the boys it was, ‘What the hell’s wrong with you, get out and play rugby and get on with your life.’”

The brutality of New Zealand children towards these “Pommie whingers” was also, he says, “part of the oppressor system at the time”.

The worst thing, says McDonald, is that we have simply ignored the great unhappiness of people like Malcolm Axcell. It’s time, he says, that we started to listen to the anguish of those who were raised “as someone other than who they were born to be”.

Words: Pamela Stirling

This story first appeared in the New Zealand Listener in 1993. Visit Noted.co.nz for more Listener content.