More than 70 people are murdered, on average, in New Zealand each year. For the vast majority of victims’ families, their grief is softened by the conviction of the killer. But whether by luck, cunning or gaps in the law, a few cases remain unsolved and for their victims’ loved ones, the pain goes on. The files of cold cases in NZ are never closed and are constantly reviewed by detectives, who hope science or a guilty conscience will one day provide the breakthrough they need.

Kirsty Bentley

Around 4pm on the final day of 1998, 15-year-old Kirsty took her devoted black labrador Abby for a stroll along familiar paths beside the Ashburton River.

After a shopping trip with her best friend Lee-Anne Kerr, the two avid Backstreet Boys fans were planning to start 1999 at the Addington races on New Year’s Day.

Instead, Kirsty was never seen alive again, apart from a tantalising but never-confirmed sighting that same evening in a hand-painted green van, in which a farmer claimed he had glimpsed a young girl behind a greasy-haired, intimidating man in his twenties.

By then, her dad, farm irrigation worker Sid, mum Jill and Kirsty’s older brother John had raised the alarm with police when she hadn’t returned home by six o’clock.

A frantic search revealed no trace until the next day, when Abby was found tied to a tree near the riverbank, with Kirsty’s underwear hanging in a bush nearby.

It was the beginning of a decades-long nightmare for the Bentleys, which tore the family apart. Only after 17 days did two cannabis growers stumble across Kirsty’s body covered with sticks and bracken in a scrubby forestry plot in the Rakaia Gorge some 50km away.

She had suffered a single blow to the back of the head and was lying curled in a foetal position, still wearing her black tank top and her blue sarong with a butterfly pattern.

More than 450 people have been considered of interest in the investigation, headed until 2022 by Detective Superintendant Greg Williams. From an early stage, he focused on Sid and John, his doubts fuelled by heavy drinker Sid’s conflicting accounts of his movements.

Only in 2022, when Detective Inspector Greg Murton took over and police offered a $100,000 reward, were Kirsty’s father and brother ruled out as suspects, with the main attention switching to Kirsty being abducted, raped and killed by a stranger, possibly a cannabis grower.

It was, however, too late for Sid, who died of cancer in 2015 while still under suspicion. Although they split within two years of Kirsty’s death and fought over the fate of her ashes, wife Jill said, “It’s great to finally have the truth out there. I wish Sid was alive to hear this. I know what hell he went through.”

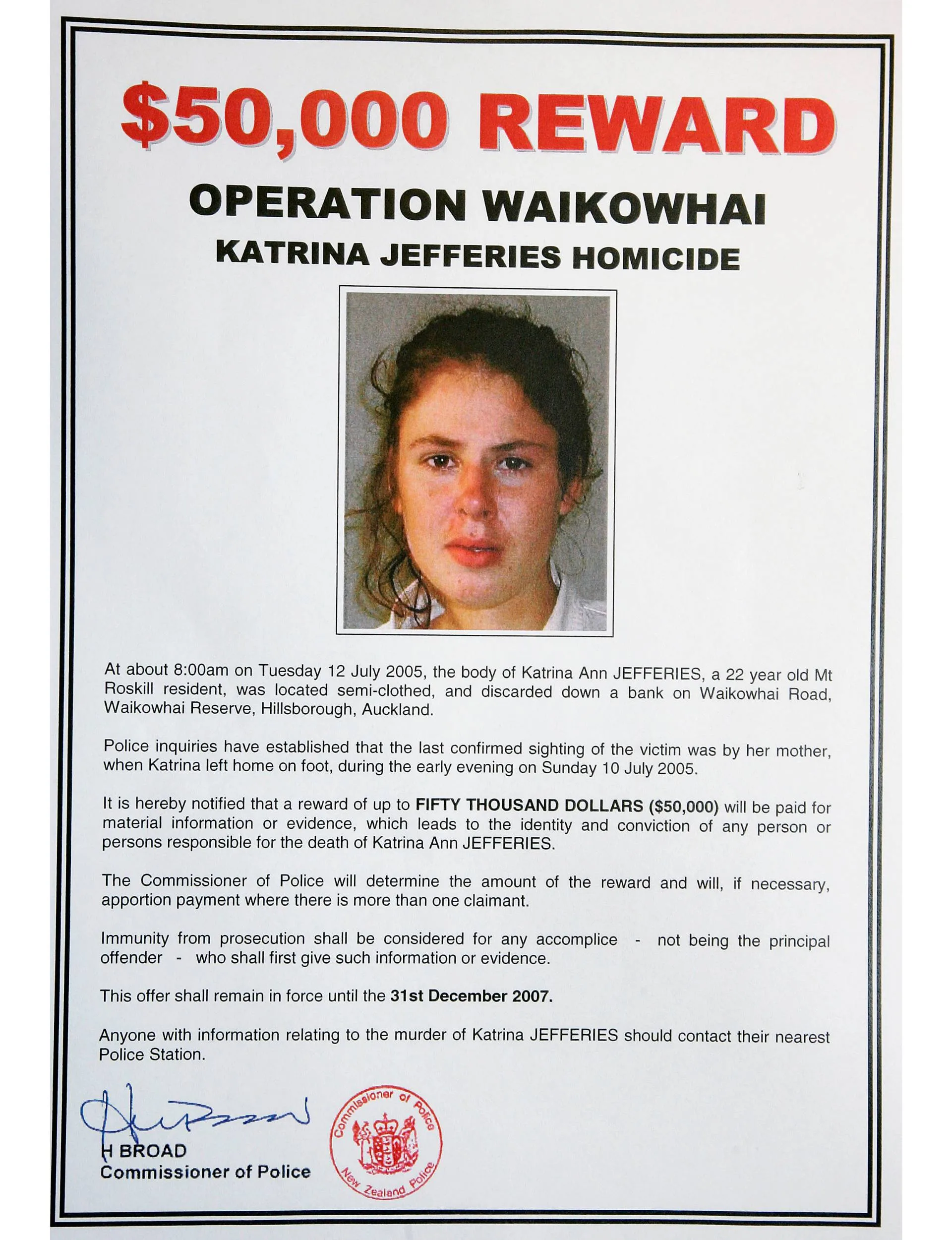

Katrina Jefferies

Two decades after her death, police have never revealed how Katrina died, beyond saying it was just “highly unusual”.

And although their investigation turned a spotlight on a man now serving a 19-year jail sentence for a series of cruel sex and violence charges, detectives have never explained his link to the troubled 22-year-old.

Their reasons are to protect a potential future trial from prejudice, but without any new evidence actually emerging, that may never happen.

Katrina lived with her 20-month-old son at her mother Nicola’s home in the Auckland suburb of Hillsborough. On a Sunday evening in midwinter, 10 July 2005, she left the house for the last time in a black tracksuit, white shirt and burgundy shoes.

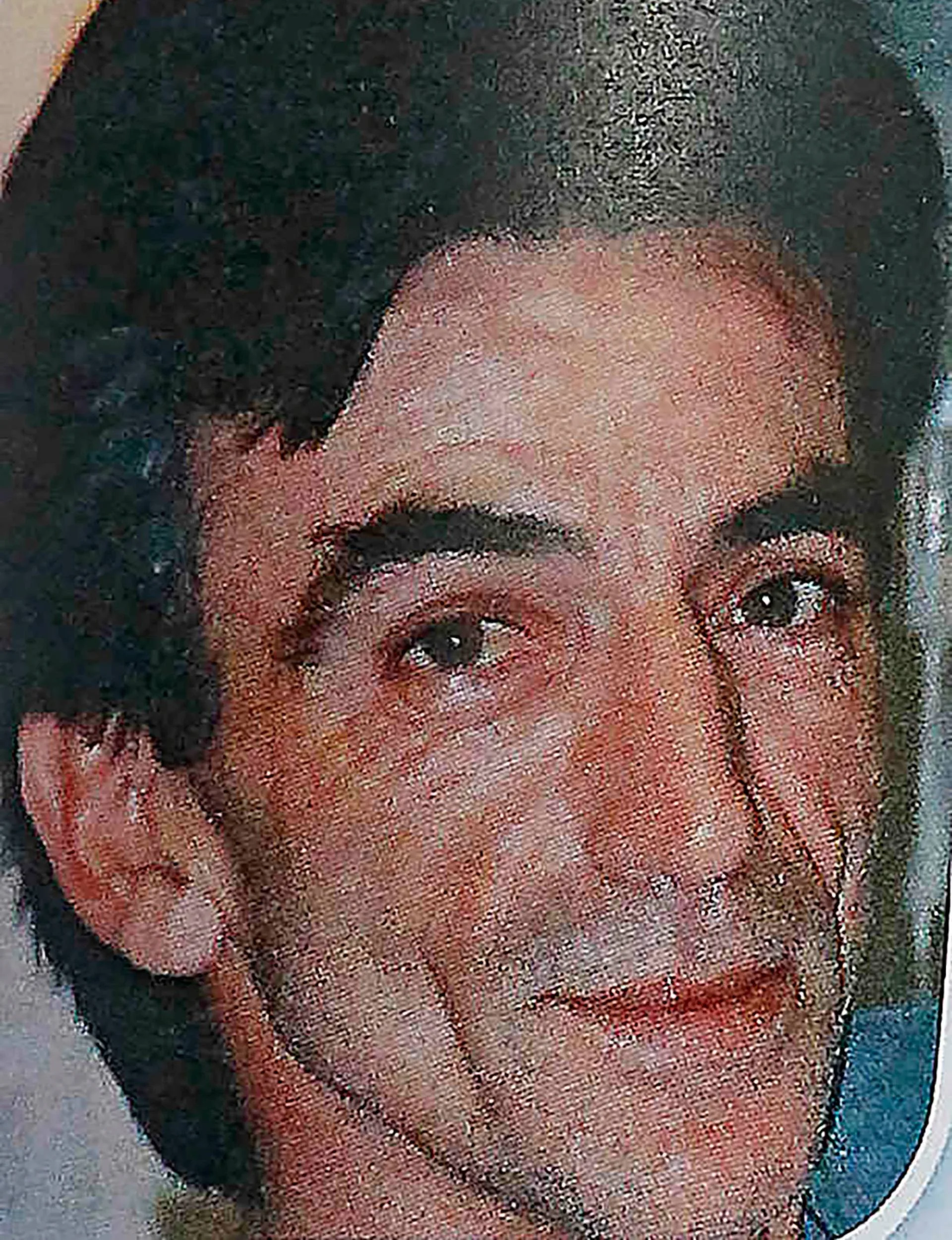

From what is known of her dysfunctional lifestyle, it’s possible to assume that she was one of a circle of young women and girls who moved in the orbit of a particular local dope dealer, although none may have known him by his full name of Michael Te Arawaka Te Huia, who is now 64.

Instead, they called him “Magic Mike”, a nickname likely earned for the drink and drugs he supplied, but also apt for a man who wove a spell of initial charm around vulnerable youngsters many years his junior but in truth was a cruel and violent tyrant.

Nicola did not think it unusual when her daughter failed to return home that night and continued caring for her little grandson not knowing that she was already dead.

Katrina liked to drink with friends that she met in the Waikowhai Reserve and it was there, wrapped in a red tarpaulin, a yellow raincoat and a black rubbish bag, that two dog walkers found her partially clothed body on 12 July.

Despite interviews with more than 750 people and a $50,000 reward, which later increased to $100,000, the investigation has never resulted in charges for her murder, only a number of false confessions.

But three women did eventually come forward to talk about “Magic Mike” and finally, in 2016, he was convicted of 21 charges against them spanning 30 years. One victim said, “I thought Magic was cool-as when I first met him, but later, when I got to know him, I was lured in, then he changed and turned into a monster.”

Nicola said in 2019, “We want justice for Katrina and it pains me that her killer is still out there somewhere.”

Ngati ‘Mellory’ Manning

“I think the police have done an amazing job,” said Rob Manning in 2014, after seeing Mongrel Mob prospect Mauha Fawcett convicted of his sister’s murder.

Aged 27 and shocked by the suicide of her sister, Mellory had been trying to move away from sex work and a drug habit, returning to live with her mother in Riccarton, Christchurch.

But on 18 December 2008, wearing a pink skirt, a blue polka-dot bikini top and a cardigan, she had gone back to her pitch on Manchester Street one last time to raise cash for Christmas presents for her family.

At 10.43pm, she sent an innocuous text to a previous client while seemingly on the move in a car. Just 16 minutes later, the hands of her watch stopped at 10.59, when her lifeless and horribly beaten body was thrown into the Avon River close to the Mob’s HQ in Galbraith Avenue.

Fawcett, then 21 and known as “Muck Dog”, had recently had the Mob’s bulldog insignia tattooed on his right cheek and had been in Manchester Street, where his job was to extract $20 from the women for every client, a “tax” Mellory was said by some to oppose.

In court, Fawcett denied being at the gang pad, saying, “I lied. People lie for many things, but I did not take part in this lady’s death.”

Rob’s confidence in Fawcett’s conviction was misplaced. A 2017 appeal revealed that over 30 hours of interviews, detectives had repeatedly lied and manipulated Fawcett who, tests showed, suffered from foetal alcohol syndrome.

His partial confession, in which he said he had hit Mellory with a pole and helped dispose of her body, was ruled inadmissible. His DNA, in any case, was not a match for the semen sample found on Mellory.

Science has, however, provided key evidence linking Mellory to the Mob HQ, thanks to a very rare mutation found in seeds stuck to the back of Mellory’s cardigan, which matched a patch of grass in wasteland behind the gang pad.

Police believe a number of people were involved in the murder and continue, after 16 years, to wait for a match to the DNA sample or for a new witness to break their silence.

Chris and Cru Kahui

“It’s natural to feel some disgust about some of these things,” admitted prosecutor Simon Moore QC at the trial of Chris Kahui for murdering his twin boys, who lived for just 84 days in 2006.

But he wasn’t talking about the defendant – rather about the boys’ mother Macsyna King, now 47, whose turbulent, shambolic childhood was only rivalled by the life of crime, drink, sex and drugs she subsequently led.

She had abandoned three older children before having a son and the twins with Kahui, eight years her junior. Visiting nurses said the babies were healthy and “thriving”, not spotting that Chris Jr already had a broken femur and both had fractured ribs.

On 12 June, Macsyna left the children in Chris’ care while she went partying overnight, only returning 12 hours later. Told that Cru had stopped breathing the previous evening, she did not feed them, change their nappies or wake them.

Eventually deciding to take the boys to their GP, the couple stopped at a McDonald’s for half an hour and when the doctor insisted they take the babies to hospital, they went home on the way, where Chris stayed.

At Starship Children’s Hospital, it was quickly established that babies Chris and Cru were already close to death, the result of traumatic brain injuries either from being shaken or slammed against a hard surface. Macsyna refused the offer of a bed at Ronald McDonald House, saying, “I don’t give a s**t. I’m going. I need my sleep.”

Chris was charged with murder only after the wider family gradually abandoned a policy of stonewalling the police. It was said he had sole care of the boys the day before, when the injuries had been caused.

He did not give evidence and the jury took less than a minute to decide on a “not guilty” verdict, effectively agreeing with his defence that Macsyna was to blame.

At a 2012 inquest, Chris did testify, but coroner Gary Evans said he was “satisfied to the point of being sure” that Chris, seemingly a quiet, subdued man dominated by Macsyna, was the killer and his version of events was “unreliable, conflicting and, on many occasions, untrue”.

Macsyna later turned to the Mormon church and married a bishop in Gisborne, where she runs a fish ’n’ chip shop under a new identity.

Chris married Marcia Ngapera, the daughter of an Auckland pastor who took him in after he was charged. They had a baby girl in 2008.

Scott Guy

Opening her front door to a policeman with tears in his eyes was the first Kylee Guy knew that her husband of five years was lying dead at the end of their farm driveway.

It was 7am on a winter morning in Feilding and Kylee, who was seven months pregnant, had been playing with the couple’s two-year-old son Hunter in their bedroom.

Scott, 31, had left as usual hours earlier to milk the cows at his family’s farm Byreburn, where he and his brother-in-law Ewen Macdonald shared the management roles.

By all accounts, Scott and Kylee had an idyllic marriage, and the young farmer was thrilled at the imminent arrival of his second son, already named Drover.

But that ended when he stepped out of his car to open the farm gate. He was shot at least twice in the neck and face with a shotgun. One thousand friends and family packed the funeral and Macdonald was a pallbearer.

It was when police quizzed young former farm worker Callum Boe that they discovered, despite his apparent grief for Scott, that Macdonald, husband to Scott’s sister Anna, had nursed a seething hatred of him and Kylee, fuelled by rivalry over who would inherit the land.

Using an axe, Macdonald had attacked a house Scott and his wife were building, painting shockingly explicit graffiti on the walls.

He had also burned down another house on the land, and he and Callum had launched vicious raids on neighbouring farmers who had caught them poaching, including beating 19 calves to death with a hammer.

Macdonald was charged with murder and his trial gripped the country. After 11 hours of deliberations, a jury cleared him of killing Scott, but he was jailed for five years for his other crimes, which he admitted.

Disputing the time of death and the number of shots fired, his defence said witnesses proved Macdonald was already at the farm when Scott died. They and others say police have ignored evidence pointing strongly to other suspects, notably a violent robber and a farm worker with a grudge against Scott.

Kylee, who funded lengthy work by private investigators, says she “100%” knows who killed her husband and her advocate Ruth Money said in 2020, “Without a doubt, there’s compelling evidence that the police have not investigated and should.”

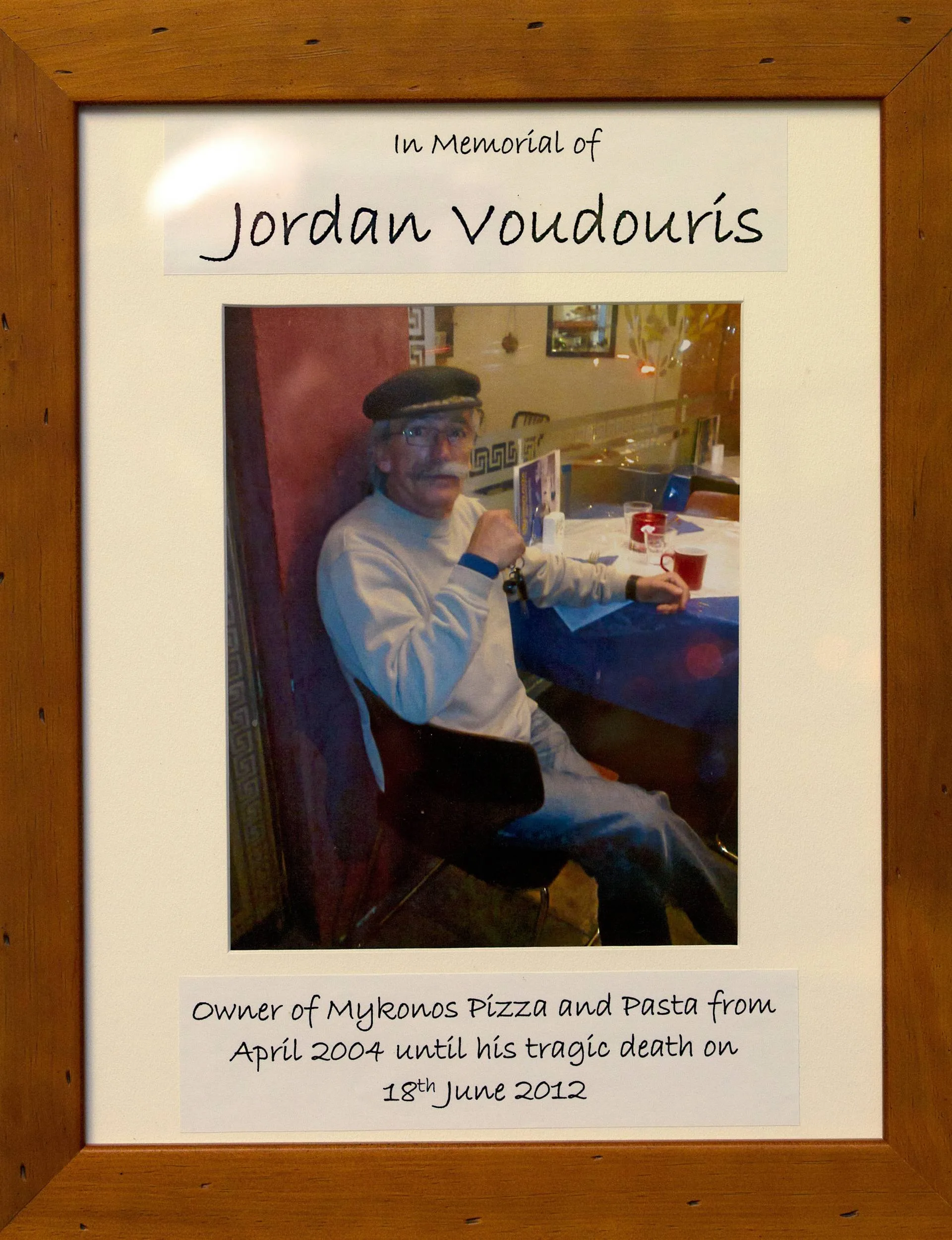

Jordan Voudouris

In the close-knit community of Paeroa, Jordan was known to all as the “Pizza Man”, as bright and bubbly as the iconic Kiwi drink invented in the Hauraki Plains town more than a century ago.

A former sailor in the Greek navy, he had followed his two brothers to New Zealand, and built a successful business and a family with four children in Auckland, before separating from their mother and moving to Paeroa in 2005.

He opened the Mykonos pizza restaurant, where his vivacious, generous nature built him a loyal, even loving following among staff and customers. But while a towering statue of an L&P bottle stands proudly on the town’s main street and is one of Aotearoa’s most photographed landmarks, a more humble tribute to Jordan is hidden away in an alleyway behind the site of his restaurant, where he was murdered on a cold winter’s night in June 2012.

The little memorial garden and a plaque in his honour marks the spot where he lay dying after a single, close-range gunshot from a .22 calibre rifle.

The previous night, as he did every evening, he had called his children in Auckland and told each of them in Greek, “Goodnight, my beautiful. I love you.”

After closing up the restaurant, he had retired to his apartment upstairs and was still searching through Trade Me on his computer at 1.30am. But something possibly disturbed him and he went down to the security gate at the back of the property, which he had installed after two recent burglaries targeting his outdoor fridges.

Neighbours heard what they later realised was a gunshot at about 2am, but Jordan’s body was not discovered until at least two hours later, crumpled against a chain-link fence in a pool of blood from a bullet wound to his abdomen. There were signs of a struggle and Jordan’s nose was broken, but his wallet, containing $200, and his watch were untouched. More than 1600 people came to his funeral.

The inquiry has identified several suspects, including two involved in other crimes who have been interviewed at length but never charged.

In 2020, Jordan’s former partner, Gwendoline Richmond, pleaded for the killer or those protecting them to come forward. “You committed murder,” she said. “How do you sleep at night?

“There’s no way this is a cold case. It’s very much a hot case. It’s alive and we want people out there to not protect this murderer.”

Read this next:

- 10 true crime podcasts worth pressing play on

- The true identity of Jack the Ripper is finally exposed after 130 years

- A shock DNA twist finally reveals JonBenét Ramsey’s killer