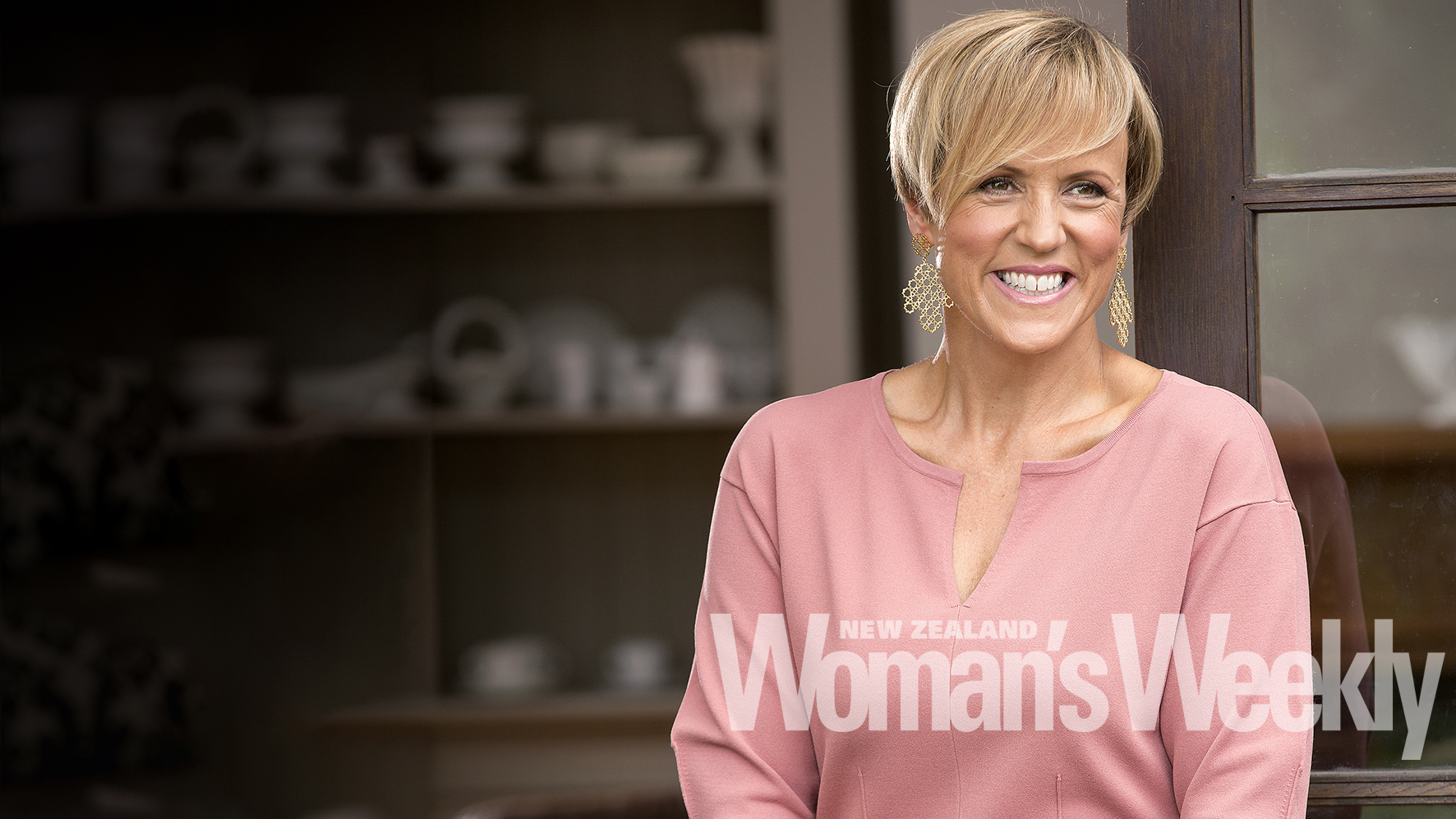

Hilary Barry is glowing, and it doesn’t take long to find out why.

“I’ve just been doing Michael Bublé!”

Excuse me?

“Well, I did him a while ago, it’s a good story, actually.”

We’re sitting in the ground floor café of TVNZ’s central Auckland offices; I press record on my iPhone and settle in.

“I flew 12 hours to LA, straight from Seven Sharp to the airport. Slept sitting up so I didn’t ruin my hair, and did my make-up on the plane. Got off the plane, changed in the toilets and interviewed him an hour later, then turned around and flew home again.”

She takes a sip of berry smoothie.

“Did my own make-up on the plane!” she repeats.

If your days are dedicated to ground-breaking climate change research or performing lifesaving operations on infants, you might not think this sounds all that above-and-beyond. Nevertheless, there are plenty of people on TV with fewer credentials than the woman sitting in front of me, who are, one suspects, a little more high-maintenance. Hilary Barry is no diva, and it’s at once nothing and everything you’d expect from New Zealand’s most experienced female newsreader.

“At 48!” She later exclaims. “The oldest woman on prime-time television at 48. That’s not old!”

Indeed, but we’ll get to that.

An industry veteran at 49 (she celebrated her birthday in December, a few weeks after our interview), Hilary’s sharp-tongued, quick-witted yet playful brand of broadcasting is at home on TVNZ 1’s magazine-style show Seven Sharp, where every weeknight she and Jeremy Wells present a mixture of light current affairs and consumer-oriented infotainment – “news you can use,” she says.

This latest role follows a period of intense change for Hilary, who spent 23 years at rival network Mediaworks before cutting ties in 2016. After a brief, but blissful, four months off, she took on the relentless early morning starts at TVNZ 1’s Breakfast before shifting to Seven Sharp in January 2018.

Last year also saw adjustments in her family life, with oldest son Finn, 18, leaving for university. Not surprisingly, she’s hoping 2019 will be “a year of consolidation”, where she can sit back and enjoy her more settled circumstances, and reflect on the lessons she’s learned about coping with upheaval. These lessons keep coming, after all.

Speaking to NEXT towards the end of 2016, she explained the difficult decision to leave Mediaworks, which followed a series of high-profile exit sat the embattled network, including that of long-time colleague and friend John Campbell, and first boss and mentor, news chief Mark Jennings.

“I just felt like I was in this constant grieving process, and I couldn’t take it any more. I actually couldn’t take it. It was time for me to go, to preserve my own sanity,” she said of the ‘dream job’ that, for that last year, simply wasn’t.

Now, two years later, the dust has well and truly settled, and having had the time and necessary distance to properly process that period of her life, Hilary has some new words of advice for women who might be finding themselves in a similar work situation.

“Believe in yourself,” she says. “Often we stay in these jobs because we’ve been there for a long time and it’s all we know, or we’re juggling family or other things and the situation suits those things, and all the while you’re just feeling miserable. Have confidence in yourself. If your job is making you feel a way you don’t like feeling, you’ve got to get out of there.”

She checks herself.

“It’s all very well and good to verbalise that, I know. It’s very hard to practise because we all have so much self-doubt. I still do! I’m not racked with self-doubt, but there are still those occasional voices in my head that go ‘I really don’t think you’re doing a very good job of this. How did you get this job? Are you really qualified?'”

Wait, does Hilary Barry get ‘imposter syndrome’?

“Yes! She does. I always want to do a good job so I put a lot of pressure on myself. And when you’ve been around as long as I have, the audience expects you to be super professional and utterly competent. So the pressure is compounded.”

As if imposter syndrome wasn’t enough to deal with, ‘new girl syndrome’ added to the anxiety of being back at work.

“Moving to TVNZ was like changing schools,” she laughs. “When you change school you’ve got to make a whole bunch of new friends and that’s scary, even in your 40s, getting to know new people. But once you do – and it doesn’t even take that long, drinking with them helps – it’s fantastic.”

Needless to say, she has no regrets about the decisions she made during this tumultuous time.

“I wish I could go back and reassure myself that everything would be okay. I think I knew in my heart of hearts that it would, but it really has been. My work family over there [at Mediaworks] will always be my family. The lovely thing about coming here is that my family just got bigger. And now it’s hard to remember what I was so scared about. So that’s what I’d say to my former self, and to others. Don’t be so scared about the future.”

It doesn’t hurt that for a self-confessed fan-girl like Hilary, the Seven Sharp gig is probably one of the best in the business. Highlights of the year have been doing Michael Bublé (of course), and a number of other celebrity interviews, including Hillary Clinton and Jane Fonda. The latter was, apparently, the more intimidating of the two.

“Only because I knew Hillary Clinton, being a politician, would be charming in the way that politicians are. With Jane Fonda, I had a feeling that if she wasn’t really enjoying the interview she’d tell you so. Plus, she’s 80, and she has an incredible warmth but also the kind of formality and propriety that 80-year-old women have.”

A lighter style of news than what she’s used to, and a far cry from its predecessors Close Up and Holmes, Hilary says that Seven Sharp is emblematic of a major shift in what audiences want. With our smartphones allowing us up-to-the-minute access to breaking news, we’re tapped out by 7pm. We need something that makes us smile.

“So it’s our job to do that,” she says. “We present uplifting stories. It doesn’t necessarily mean that every story is happy, but we like them to be hopeful, relatable, or at the very least, stories that aren’t going to depress people. There’s been extensive research done and this is what people want,” she explains. “And in this current environment, it’s adapt or die.”

Some changes have been harder than others to adapt to. In an interview with The Listener in 2017, Hilary chastised herself for losing her composure during John Campbell’s on-air farewell.

In mid-2018, a newsreader in the US was similarly overcome on a live bulletin about children being separated from their families at the Mexican border. Apologising for her behaviour on Twitter, the newsreader was met not with criticism, but praise, by a viewing population that in the face of so much inhumanity, was seemingly loath to condemn the newsreader’s genuine humanity. So what’s Hilary’s take? In today’s world, does ‘professionalism’ put a journalist in a particular category? Does absolute objectivity make one out of touch?

“I have that classic broadcasting training of not being emotionally invested in stories, just delivering news impartially,” she says.

“So when I show emotion I do kind of groan inwardly, because I know the traditionalists watching will go, ‘For goodness sake, you’re the newsreader, get a grip.’ That being said, I am just myself on air, and I am an emotional person. And I do get choked up relatively frequently. Having spent so many years being taught to do things in a certain way, I do feel slightly guilty when a little bit of ‘me’ shows through. But I don’t beat myself up over it. I guess I’m kind of somewhere in the middle of the spectrum of old-school journalism and this new world that we live in.”

It makes the job easier, says Hilary, that New Zealanders are, on the whole, “a nation of people who are kind to one another”. She has one bone to pick, however, and it’s not a new one.

“I’ll tell you what,” she says, fired up at how scandalised people were when she was cast on Breakfast opposite Jack Tame – 19 years her junior.

“The audience largely did not handle it. And that’s on them. TVNZ was really brave in many ways to team up Jack and me. They took that bold step. But the audience feedback was resounding – people couldn’t handle an older woman presenting with a younger man. And truly, shame on them. They tell us they’re open-minded but they’re so used to the formula of a younger woman and an older man that they found the reverse difficult to deal with.”

Audiences were more receptive when Jeremy Wells took two weeks’ leave from Seven Sharp and Anika Moa – brash, tattooed, Maori, gay – filled in.

“I think people liked the dynamic. It was different, and it was a little bit risky. But again, it shouldn’t have been! It shouldn’t have been different, it shouldn’t have been breaking new ground. In 2019 we should not be fighting to make this an okay thing. And it’s not the broadcasters, they’re the ones going, ‘Let’s try some new stuff, let’s team up two women, let’s put an older woman with a younger man, let’s give these things a go.’ And yet, there are still those viewers for whom changing the arrangement that’s been around for decades is just too much.”

If there’s one change that Hilary is looking forward to in 2019, albeit with some trepidation in her voice, it’s turning a year older.

“I’ll be 50 in December, so I’ll be spending a bit of time contemplating what that means.”

She perks up.

“Actually, I think I might have a whole year of celebrations. Perhaps one per month… no, several!”

With that on her plate, it’s probably just as well she and husband Michael will have only their youngest son – 16-year-old Ned – at home. As anyone who follows her on Twitter will know, there’s enough stress and anguish in parenting just one teen. Hilary kept followers on tenterhooks in November as we waited in solidarity for Ned to tell her how one of his NCEA exams went.

“Sixteen year old currently being written out of the will,” she wrote when, 30 minutes after the exam finished, she’d still heard nothing. The play-by-play we’d been getting until then ended, and one wondered whether the news was not great.

“Oh no, in the end I didn’t post an update because when he got back to me it was such a non-event. He just texted ‘good’. Unbelievable! They’re so blasé.”

As strong as her maternal instincts are (having children was always a life ambition), she draws the line at being ‘the mother of the nation’. Though an honour, she thinks the bestowing of this title upon her in recent years is not only very premature, but quite possibly accidental.

“I feel like someone got confused one day and called me that, thinking I was Judy Bailey,” she laughs. “I’m not old enough to be the mother of the nation!”

She has some alternative suggestions.

“Friend of the nation? Drinking buddy of the nation? Mate? Aunty?”

And makes another valid point.

“Who’s the father of the nation? Dear God, don’t let Jeremy be the father of the nation.”

All that being said, mentoring the next generation of journalists is, in her mind, one of the most important aspects of her job.

“I get right amongst them in the news room. Or if we’re out doing a story for Seven Sharp, often one of the younger producers will come along so we’ll talk through strategies and what we’re doing and what worked and what didn’t. I love that sort of stuff.”

A key piece of wisdom for fledgling journos?

“Beware of Google,” she says wryly.

“It makes everything a little too easy. We used to do a lot more fact-checking back in the good old days.”

(An aside: both Hilary and her publicist will be pleased to know that after using transcribing software to process the audio for this interview, and it attributing to Hilary a number of unmentionable slurs, I conceded that technology is not always our friend, and proceeded to manually transcribe the slur-free version from which I am referring now). Still, she’s not some old curmudgeon, grieving for the death of journalistic integrity. Adapt or die, remember?

“I think when everyone’s got a mix of experience it’s good to share that,” she says.

A perpetual student of sorts, there’s one thing Hilary has yet to master. Or even attempt, as it were.

“I am absolutely set on learning the cello.”

I remind her that she said the same in her previous NEXT cover story.

“I did! And have I? No. But don’t you worry, that’s still my life ambition.”

I tell her I’ll check on her progress in 2020.

“I will have done it by then. Oh, I absolutely love the cello.” She starts gesticulating. “It’ll happen and you can have the scoop. When I take my first cello lesson you will get the scoop.”

Stand by for updates.

.jpg)