There are times you wish that somehow, even just for an hour, you could bring back long-dead historical figures so they can see how far – in some respects – we have come. To witness a moment they couldn’t even have dreamed of. An odd thought perhaps, but after hearing about a particular episode in the making of new movie Suffragette, you might just feel the same. The film tells the story of Maud, a poor young mum working as a laundress in London in the years before World War I who – reluctantly at first – joins the struggle for the right to vote. Maud is fictional; you won’t find her in the history books, but she’s also very real – a com-posite of the women history has forgotten, the nameless individuals who have remained in the shadows, even though their contribution to women’s suffrage was immense. So yes, it would be gratifying to whisk one of these courageous souls to the present day, to watch the filming of a scene from Suffragette inside London’s Houses of Parliament. Not only would our time-traveller be left open-mouthed to see a woman director in charge, and to watch the stellar – mostly female – cast re-live their story, they would feel honoured to be present for another piece of history in the making. Because this was the first feature film crew – ever – to be allowed to shoot inside London’s Houses of Parliament.

But then talk to the film’s 45-year-old director, Sarah Gavron, and you quickly realise she’d never let a little thing like a few musty old rules stand in the way of authenticity, of getting her film just right. Of the push to get that ground-breaking permit, she laughingly tells NEXT “Yes, I said let’s get a bit suffragette about this!”

This isn’t the first time the Bafta award-winning Brit and her screenwriter Abi Morgan have cast the spotlight on an ordinary young woman’s struggle. In 2007 Gavron’s debut feature film, Brick Lane, told the story of a 17-year-old Bangladeshi starting a new life in London after her arranged marriage to an older man. As with Suffragette, the drama makes us look at a particular period of history through fresh eyes. While it plays out against the backdrop of rising anti-Muslim sentiment following the World Trade Centre attacks, Gavron remarked at the time, “You’d see 9/11, but through this very particular perspective, and only in glimpses”.

While focusing her lens on Everywoman, Gavron’s own background is nothing if not illustrious. She is the daughter of the late Lord Gavron, a British printing millionaire and Labour life peer, and her mother is Nicky Gavron, a former London deputy mayor. It’s from her mother, she says, that she gets her social conscience.

Sarah Gavron behind the scenes.

Gavron, who by the way is nowhere near as intense as all of this makes her sound – she laughs often and comes across as someone you’d happily go, say, shoe shopping with – began her career as a documentary filmmaker. Perhaps this is where she gained her brilliant ability to make us inhabit someone else’s skin.

Even that of a baby in an incubator. This Little Life, the film for which she won the Women in Film and Television’s best newcomer award in 2003, was the dramatised story of a premature baby struggling for life – told from the point of view of the infant.

That filmmaking accolade was a significant one for Gavron. Not only did it mark her out as a talent to watch, it gave her the platform to address something close to her heart. At the time of the award she said “Women in Film and Television is such an important body. It is a struggle to break in [to TV], so you need all the help you can get”.

The persistence of a ‘celluloid ceiling’ in the industry has been widely reported, with San Diego State University keeping yearly tabs on employment of women in film and TV. And the results aren’t exactly pretty. Which is why Suffragette – starring Meryl Streep as Emmeline Pankhurst, Carey Mulligan as Maud, and Helena Bonham Carter as feisty lawbreaker Edith Ellyn – arrives in good time. The story may be 100 years old, but issues of gender equality are fresh in the headlines. Not least right here in New Zealand, despite us having won the right to vote a good 20 years before the film’s action takes place.

Back in early-1900s London, the battle for women’s suffrage was being fought with bricks and bombs (if you’re thinking it was all angry parasol-shaking and women chaining themselves to railings, think again). Reel forward 100 years and, yes, we have made the sort of gains that put a woman at the helm of a film shot inside parliament. However, each in our own way, we’re still fighting. On the other side of the world, one talented woman is doing it armed, not with explosives, but with something perhaps more powerful. A movie camera and an ability to make us think.

We spoke to Sarah Gavron on the eve of the film’s screening in New Zealand.

At a Suffragette publicity event.

Q: What made you focus on that particular moment of the suffragette struggle? From 1912-13… rather than, say, when women in Britain actually won the right to vote?

The suffragettes’ history was long, over about 40-50 years, but we spent six years researching the film and we found that period, just before the First World War, was a time of heightened militancy by the women, and of heightened brutality by the state. Later, when the First World War broke out, the women joined the war effort and the whole thing [militancy] lost its momentum. So there was this window of time that was interesting to document, where the struggle was extremely intense.

Q: Elements of the story are shocking. The way the state hounded the women and spied on them, the lengths the women were prepared to go to, making bombs and so on. Did anything surprise you about the history when you were researching it? We weren’t aware of any of this!

[Laughs] Ask any history student in the UK and they would say the same thing! When people think of suffragettes they might think of the Mrs Banks character in Mary Poppins. The story of these ordinary working women, a laundress like Maud, was really hidden. So it felt like a story that needed to be told, that was timely because women are still fighting over similar issues today, over pay and equal rights and so on. We don’t hear a lot about women in history but when we do it’s middle-class women. But ordinary working women were also at the forefront of change. And unlike the wealthier suffragettes, they had so much to lose. Their jobs, their families; they sacrificed so much. What surprised me was the brutality – the state really saw them as a huge threat. For example, the force-feeding (which now of course we class as torture) – and [suffragette] Emily Davison endured it 49 times! What they were prepared to go through was incredible.

Gavron filming with Carey Mulligan.

Q: The film feels very relatable, not at all like a period piece. For example that moment where Maud and Violet [a co-suffragette] are in Maud’s grim new ‘digs’, when she’s just been kicked out of home, and it’s a real low point. And then the bed collapses and they fall into fits of laughter. Were all these moments written into the plot, or did some of it just happen and evolve because of the chemistry between the actors?

It was both. As part of our research we read the letters women wrote in prison and there was a real visceral sense of them as people you could relate to. And you got a great sense of the camaraderie among them. It was important to show that. Also Abi [Morgan, scriptwriter] was great at adding in bits as our research progressed so it was constantly evolving. It’s also that 100 years on, women still face a lot of issues, so the characters and their story resonate because we still have these problems of inequality today.

Q: As a woman in a male-dominated industry, do you feel a responsibility to tell inspiring stories about women and with good strong roles for female actors?

I grew up in a political household and my mum had a great social conscience so, yes, I am passionate about these issues, and about reminding people how important their rights are, that they were hard won.

Q: This was a female-led movie, both the cast and crew. That is unusual. How different is it working in a mostly female environment? Is there anything women bring to the process that a male-dominated crew doesn’t…

On this film there really was a sort of female energy, largely due to the subject matter, I think…

Q: So some kind of parallel with the movie…?

Er, yes, I mean [laughs] – nothing like on the scale of what the suffragettes were doing of course! – but a sense of doing something quite ground-breaking here… In fact Brendan Gleeson [who plays Inspector Steed, in charge of spying on the activists] said he’d never been on such an estrogen-filled set!

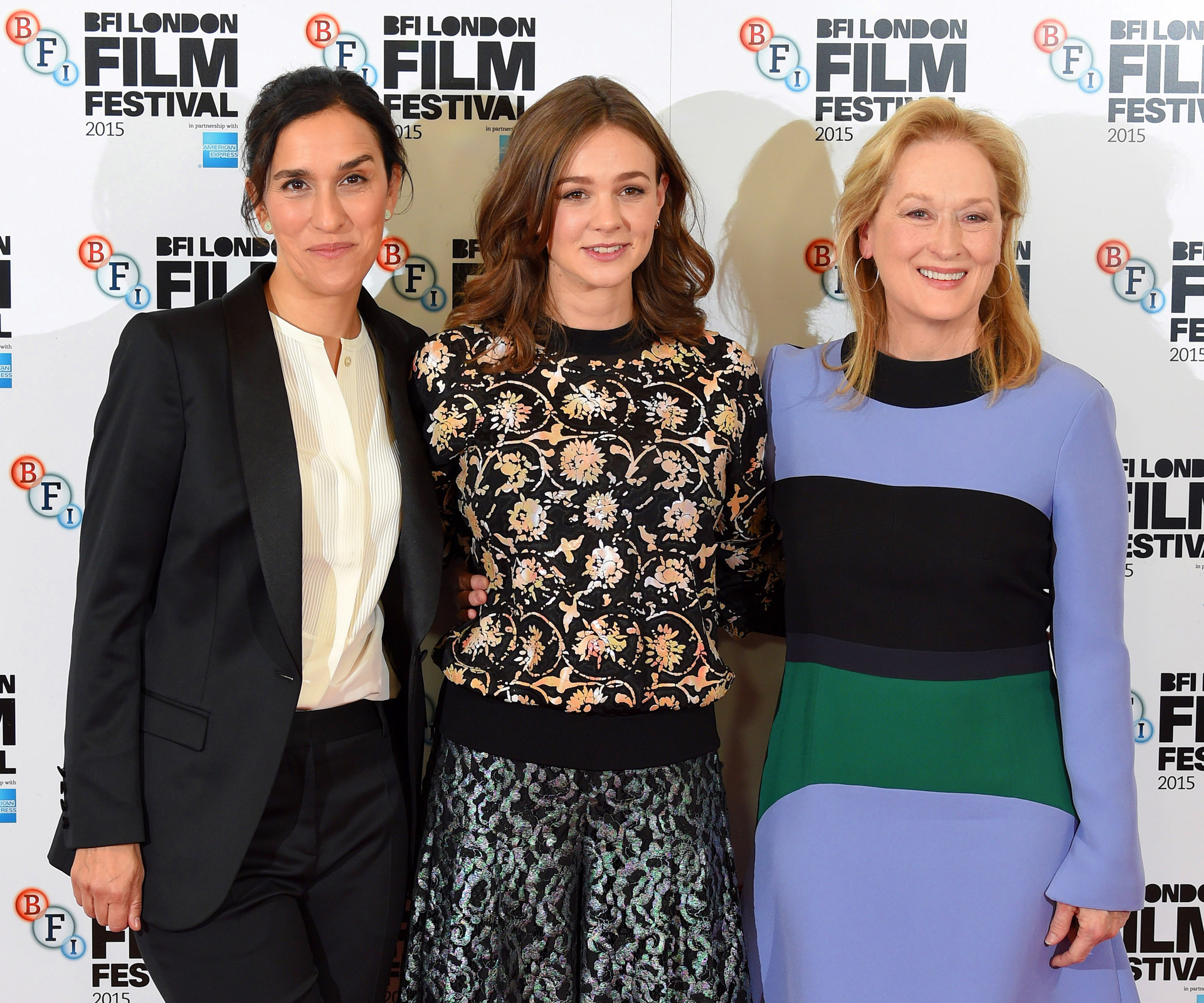

With Carey Mulligan and Meryl Streep.

Q: Why was it important to you to film inside the historic location itself, to shoot inside Parliament?

We felt it was very important to gain access to the actual rooms where these events took place. There was already some talk about letting in film crews but we really wanted to push for access. There was a sense of history because we had Helena Bonham Carter, whose great-grandfather Herbert Asquith was prime minister at the time and an adversary of the suffragettes. And Emmeline Pankhurst’s great-great-granddaughter Laura has a small part in the film.

Q: From a Kiwi perspective, it’s shocking to see all this going on so long after New Zealand got the vote [in 1893]. A friend of mine even said she was really angry when she left the cinema! What do you hope audiences take away from the film?

Yes, I’ve heard of people reacting angrily… There’s also been applause, and gasps when people see Switzerland only gave women the vote in 1971 [a list of dates when countries granted the right to vote roll before the closing credits]. I hope it makes people think, especially about speaking out, standing up for what you believe in, and never taking what people fought for, for granted. I’ve heard of groups of young women who’ve seen Suffragette who’ve said ‘we’ll never ever not vote again!’

Q: What other stories are there out there that particularly appeal to you as a director?

I’m very committed to female-centric roles. We know what the men were doing at different points of history, but the women’s stories are hidden. Plus more than 90% of films are seen through the male gaze. But I don’t know exactly what my next project will be at this point.

Q: Finally… what was it like to work with Meryl!

We were amazed that we got her, but she was just great. Very level-headed and she was so generous. She even stayed on after her filming so she could help off-camera [she was an extra voice for some of the crowd scenes]. She turned up with her [1985 romantic drama] Out of Africa shoes because she said it was hard to get authentic Victorian shoes! Having her was great; she’s such a great advocate for women in film.

Words by Maria Hoyle

Photos by Getty Images, iStock Images and supplied

.jpg)