Guerrilla tactics, jungle ambushes and chemical weapons – to many Kiwis, the Vietnam War barely exists beyond action movies. A complex war that left a bad taste in the mouths of many New Zealanders, the conflict seems profoundly foreign and hard to define. However, the war can be seen as a force for political and social change, and a key factor in New Zealand’s coming of age.

The Vietnam War is well documented. Prime Minister Keith Holyoake had put off indirect pressures from America for several years, but in May 1965, he concluded that if our nation wanted to have good relations with the United States, then we had little choice but to join the fight. As Kiwi troops assembled alongside American and Australian soldiers, it was the first war in which New Zealand did not fight beside our long-standing British allies.

Victoria University Vice-Provost Professor Roberto Rabel says responses to the conflict were muted at first, but the country’s attitude to the war changed dramatically between 1965 and 1972, when Kiwi troops were withdrawn.

“We always saw the war as a very messy situation,” he explains. “We were doing it not because it was a winnable proposition, but because we generally shared the view of the US that we needed to contain communism in Southeast Asia. But over the course of the war, more and more New Zealanders came to conclude that communism wasn’t a real threat to us. This was a big shift in thinking over the late 1960s to early 1970s.”

Indeed, as the war dragged on, so did the discomfort surrounding the conflict. South Vietnam began to look like an unreputable ally, and unrest was building internationally over mass bombings and the use of chemicals such as napalm. Suspicions were mounting over whether America was telling the truth about the nature of the war, and it started to look as if the US was bullying its allies, let alone its enemies.

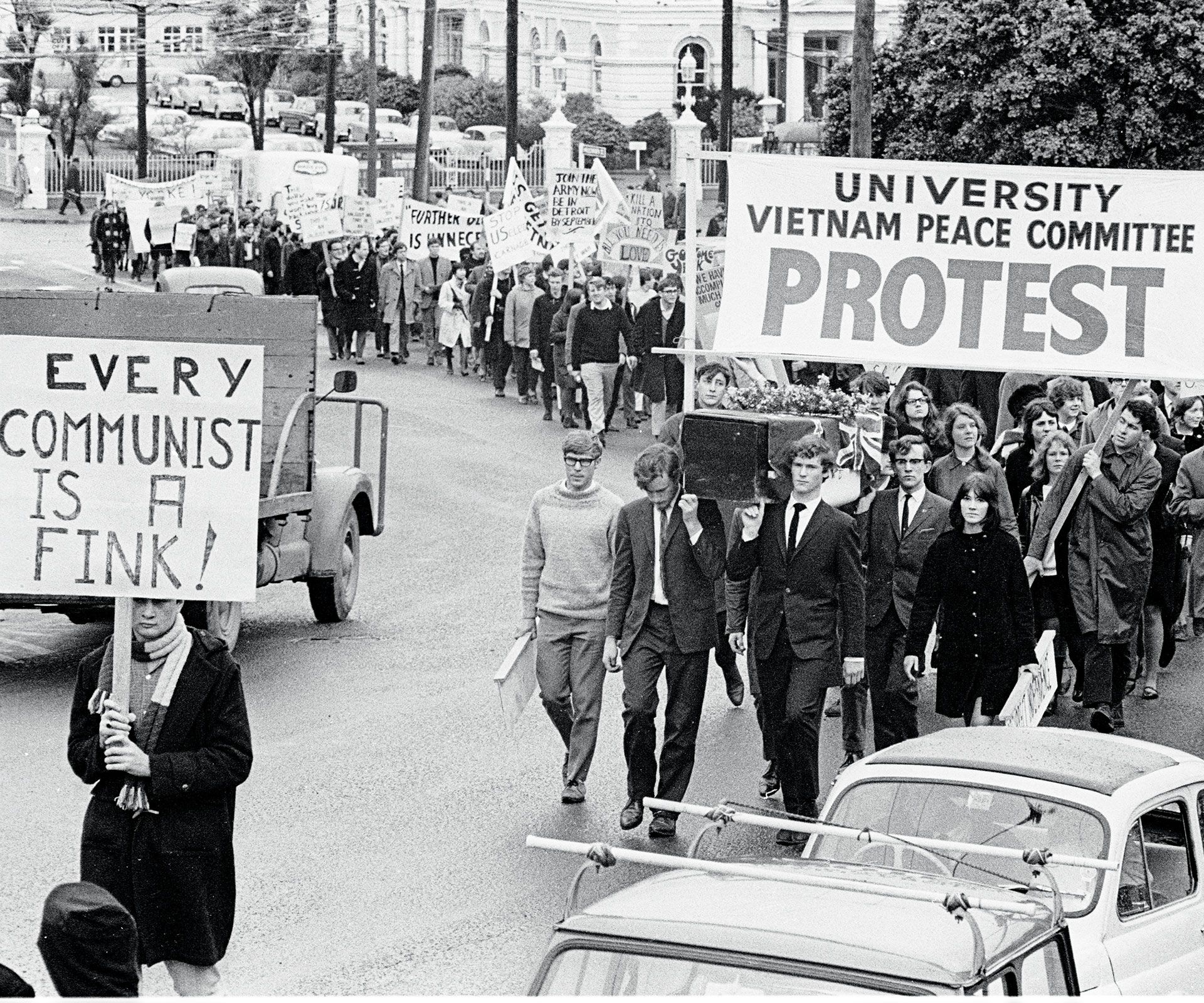

Victoria University students protest against the war, 1967.

In the main centres, anti-war protests gathered momentum throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s. However, for small-town New Zealand, the situation in Vietnam didn’t impact on everyday life.

“The anti-war movement didn’t have mass mobilisation,” says Roberto, who has published a book on the politics of the conflict. “For most New Zealanders, the war was something pretty distant. It wasn’t something that touched their lives – rugby mattered more. By 1972, as we were ending our involvement, a lot of people were taking the view that we shouldn’t have been there, but New Zealanders did not really engage with the war; that was part of the government’s political management of it.”

However, the Vietnam War protests did provide a taster for many politically-charged young people to dabble in public demonstrations, and paved the way for some of the country’s largest protest movements.

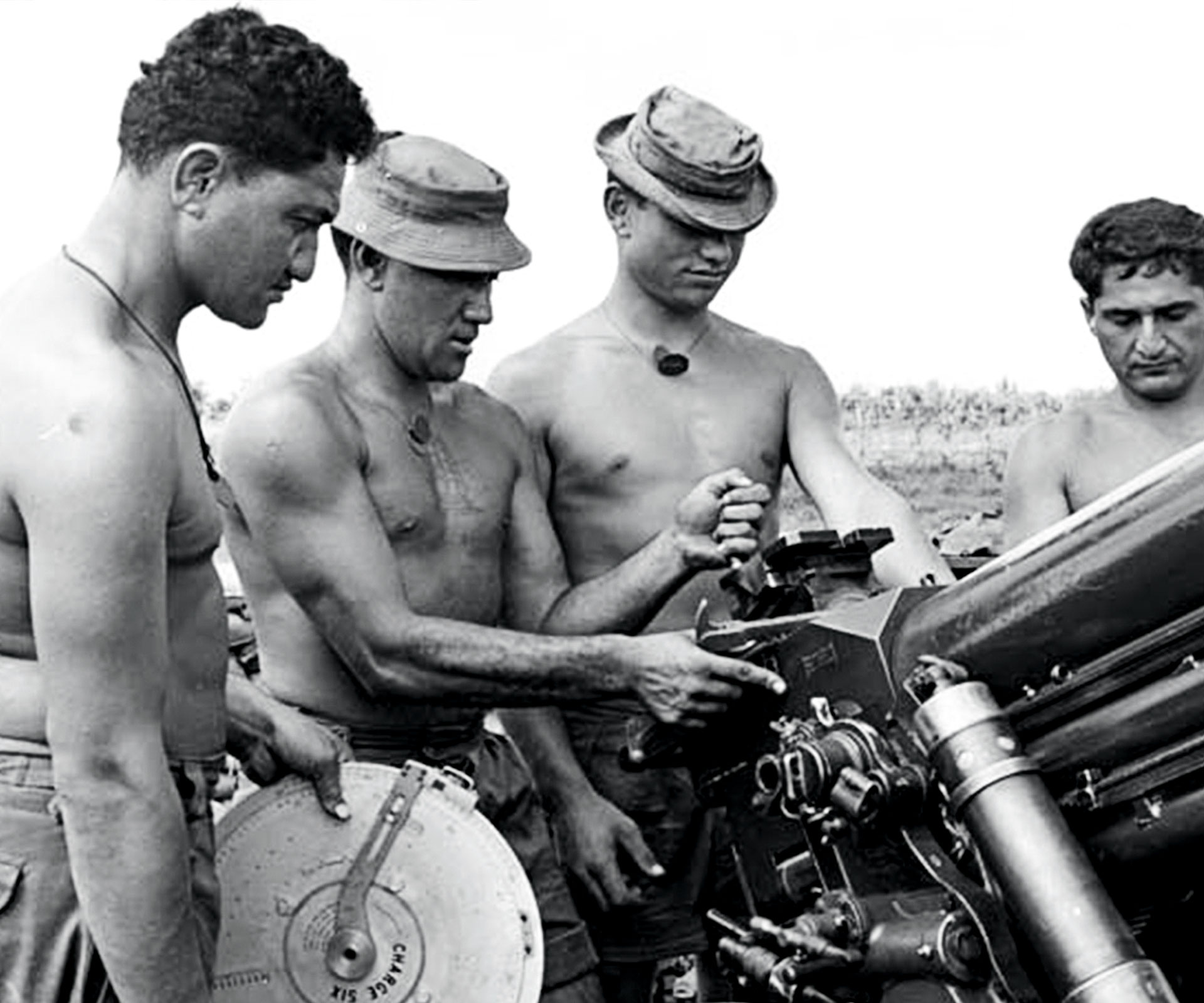

Part of New Zealand’s involvement in Vietnam was training local soldiers – here they are being shown how to operate a machine gun.

Massey University history lecturer Dr Rachael Bell says although the protests may not have attracted huge numbers, they made an impact.

“They were large in comparison to the number of New Zealand troops that were sent. It was a schooling ground for all the later protests, particularly the Springbok tour. Many people who were pivotal in organising the Springbok-tour protests cut their teeth on the Vietnam War protests.”

Despite the relatively small turnouts, the anti-Vietnam War demonstrations represented the beginning of a shift in national consciousness, a new belief that Kiwis could band together to make their voices heard, and a move towards seeing ourselves as global citizens.

“It was the start of a belief in collective moral muscle,” says Rachael. “During the late 60s, 70s and 80s, New Zealand culture was overhauled in many ways. The Vietnam War was the start of New Zealand being rocked out of its complacency.”

As protest movements and social upheaval gathered steam, political change was slowly building, too. The Vietnam conflict had a profound effect on foreign policy and international relations, and its legacy remains today.

New Zealand gunners loading an L5 Howitzer into an armed personnel carrier.

“Following the defeat in Vietnam, governments have been careful to explain why sending troops abroad is in the interest of New Zealand and the international community, rather than implying we are involved simply because an ally wants us to be,” says Roberto.

This sentiment was most recently reflected in John Key’s speech to parliament, when he stressed his belief in how important it was for New Zealand’s interests, values and independence to send troops to Iraq. “We have carved out our own independent foreign policy over decades and we take pride in it,” he said in the address. “We do not shy away from taking our share of the burden when the international rules-based system is threatened.”

“There is a lot more questioning since the Vietnam War,” says Roberto, who is National Vice-President of the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs. “In WWII, Michael Joseph Savage said, ‘Where Britain goes, we go.’ That was enormously important and very few challenged it. Now you could never say, ‘Where the US goes, we go,’ or ‘Where Australia goes, we go.’”

The Vietnam conflict brought foreign policy into the spotlight as an issue for public debate, rather than a matter of bipartisan consensus behind the closed doors of parliament. It triggered a wave of public concern for foreign policy that had never been seen before, and the interest swelled even further in response to the Springbok tour and nuclear-weapons testing.

For the professional soldiers, the war was a job, rather than a political issue.

Dr Ian McGibbon, historian and author of New Zealand’s Vietnam War, says the Vietnam conflict prompted New Zealand to forge a new independence. “The attitude in the 1960s was that we were part of the ‘Western team’ and had to do our bit and make our contribution. [During the Vietnam War] there was a groundswell of opposition to the American domination of our foreign policy. That fundamental shift away from being ‘part of the club and proud of it’, to being more independent, became a sort of mantra later on in the 1980s.”

For the New Zealand troops serving in Vietnam, the war wasn’t about politics or protest marches. The New Zealand combat forces were professional soldiers, not regular civilians like those involved in the World Wars, and they simply wanted to follow government directives and get on with the job.

With Maori and Pakeha soldiers fighting side by side, instead of in separate units, military historians say the war marked a turning point for cross-cultural bonds in the New Zealand defence force.

“Maori soldiers really came of age in Vietnam,” says Ian. “They made up about 33 per cent of the [Kiwi] troops, and performed outstandingly; it created a new ethos in the New Zealand Army. In the last 20 years of the 20th century, there was a new emphasis on biculturalism in society, and the performance of Maori soldiers in Vietnam was part of that.”

A group of Maori gunners.

Over the seven years New Zealand was at war, about 3000 Kiwis spent time in Vietnam; in surgical teams, as engineers, or as part of combat forces. In what some consider a bid to help play down our contribution, the government was careful not to have too many troops serving at any one time, with a maximum of about 548 soldiers at the peak of our involvement.

The effort in Vietnam cost the lives of 37 Kiwi servicemen, a nurse and a Red Cross member. As troops withdrew from the conflict in the early 70s, soldiers came home to widespread anti-war sentiment and a reception that was perceived by many as cold and indifferent.

“Unlike any of our other wars, the legacy of bitterness among the soldiers is one of the most noticeable,” says Ian. “Partly because the soldiers came back and felt their contribution wasn’t given the recognition it should have been. That’s the problem for the veterans –nobody wanted to talk about it.”

The plight of the Vietnam veterans was addressed by Helen Clark in 2008, when she offered an apology to the soldiers and gave her support to those suffering from ongoing health issues as a result of exposure to the toxic defoliant, Agent Orange.

Decades after the deadly conflict in Vietnam, New Zealand’s most unpopular war of the 20th century is still not widely spoken about. Although there are no small-town war memorials or remembrance days, the defeat in the Southeast Asian jungle helped our country to re-define its place in the world. The Vietnam legacy lives on in the form of a proudly independent New Zealand

Words by: Sara Bunny

Photos: Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.