On the heels of her father’s devastating dementia diagnosis, Leslie Harris, along with her mother Margaret, found themselves often wondering where to unearth the right resources and support during tough times.

Information was available – it just took so much time to find and the family found their questions weren’t easily answered.

“Almost 70,000 New Zealanders are living with dementia, but when I started talking to other people in the same situation as us, I realised my frustration with searching for information and struggling to find out what help was available was almost universal,” says Leslie, 53.

“I remember sitting with Mum and saying, ‘When this journey with Dad is over, I’m going to do something that makes a positive change for people living with dementia and their carers.'”

Seven years on, her experience has motivated Leslie to create the website Harris List. It’s named in honour of her beloved late father Garth Harris and aims to be a “one-stop shop” for families of people living with dementia to find the resources needed to navigate their way.

Key topics include diagnosis, types of dementia, how to get assessments, money matters, funding, medication and respite care.

“Dementia doesn’t need to be scary,” tells Leslie, from her mother’s Auckland retirement village.

“In fact, we learnt a lot more about Dad after his diagnosis. Before that, he was a very closed book.”

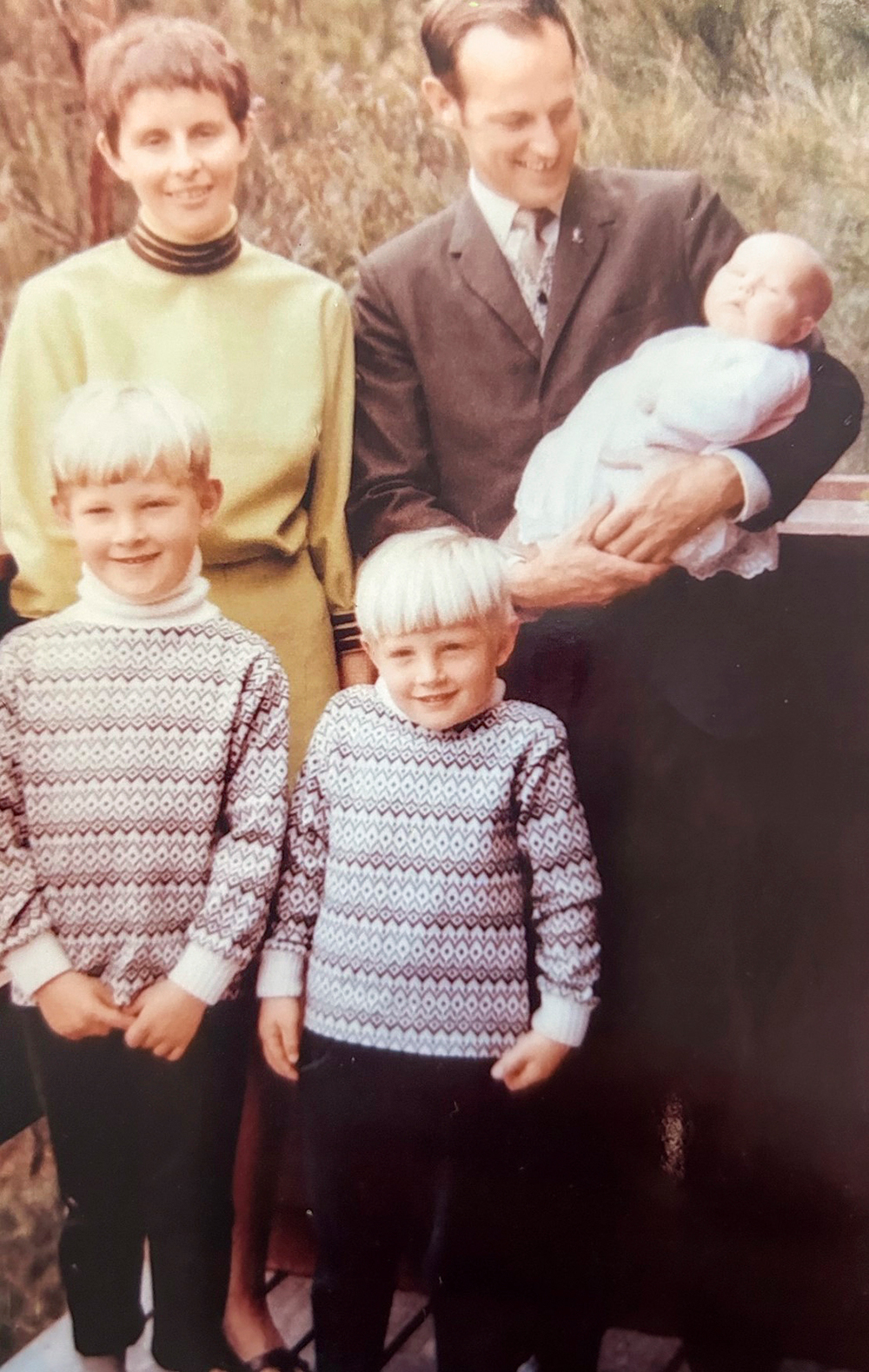

Adds 83-year-old Margaret, “Yes, he was a placid, reserved man… a very intelligent man who was a civil engineer with a PhD. He always had a smile on his face. That’s why I agreed to marry him after six dates!” she laughs.

Margaret knew Garth was “the one” after six dates!

When Garth was in the early stages of dementia, he started freely sharing his often-painful childhood memories with his family – many sufferers revert back to their childhood years – and told them about how his father had been gassed in World War I.

“It was amazing hearing his stories,” agrees Leslie. “He would go on and on. I started taking notes about various relatives I had never heard about before! So, the unexpected gift was that dementia gave us a broader knowledge of Dad’s life.”

Margaret says she first noticed worrying symptoms in Garth when he was in his late-seventies and couldn’t remember directions to a place they visited regularly.

“I thought it was very weird. I saw a decline in his memory and 18 months later, a neurologist diagnosed him following a brain scan.”

Margaret admits she initially didn’t want anyone to know her husband had dementia, because of social taboos attached to it.

“When people get a dementia diagnosis, they often get left behind socially,” explains Leslie. “People stop visiting and friends drop off because they just don’t know what to say.

“Your loved one might turn into someone you don’t know. And they often don’t know you either. Dad thought I was his sister at times, but I rode with it and learned to be economical with the truth.

“You don’t need to correct them all the time when they forget. I just wanted to enjoy every moment with him.”

Following Garth’s passing in 2020, Leslie decided to study online for a Diploma of Dementia Care through the University of Tasmania in Australia, which also offers a free online eight-week “Understanding Dementia” course to the international community.

It was a big undertaking for the single mum-of-three, who had never been to university before, but she was determined to continue her father’s passion for research and learning.

After recently graduating, Leslie now plans to develop an education programme on how to keep communicating with someone with dementia. She hopes to take it into Kiwi schools so children can learn they don’t need to be afraid of a grandparent with the brain disorder.

“One of the best pieces of advice I have for families is to create a memory box for their loved one with dementia,” she says.

“Pick out some of their items such as a favourite lipstick or cologne, an old piece of music or photograph, a newspaper cutting or a hanky that might trigger particular life moments.

“So later on when you visit them, the loved one can take something out of that memory box and it can spark a great conversation that is meaningful for that person.”

She says research shows exploring and talking about things from the past can help to trigger short-term memories by bringing to the fore long-term memories.

The doting parents with baby Leslie, Philip (left) and Simon.

“If you get cancer, people generally don’t ignore you,” she reflects. “But if you get dementia, your friends or grandchildren can be a bit scared to know what to talk to you about.

“That’s something that I really want to work on – educating people to remember that those with dementia still have value, they still have much to offer. You just need to learn ways of how to communicate with them.”

For more information, visit harrislist.co.nz.