As she curls up on the couch in her townhouse on the outskirts of Christchurch, Lilia Tarawa looks every bit the successful businesswoman.

With her runway looks and easy laugh, the 26-year-old business mentor chats about leadership, her passion as a budding author and her drive to help other people fulfil

their potential.

But take a second look and there are subtle signs of Lilia’s unorthodox childhood. Her glossy mane of hair is uncut and swings almost halfway down her back. And although she’s single, a ring sits defiantly on her wedding finger.

“After all these years, some things never change,” laughs Lilia. “As hard as I try to rebuild my life, parts of Gloriavale are ingrained in who I am.”

For the first 18 years of her life, Lilia grew up at Gloriavale, a Christian sect in the rugged Haupiri Valley on the West Coast of the South Island.

There, female devotees turn their back on the outside world and dedicate their lives to God, donning a dour navy uniform, being “good”, submissive wives and having large families of up to 14 children.

They leave their hair uncut and, for many, it reaches down to their calves. Girls marry as young as 16, but wedding bands carry no meaning because the union is with God.

“Who I am and what I stand for traces back to Gloriavale,” asserts Lilia. “I am passionate about empowering women because it was women that were so suppressed inside the compound.”

Lilia’s maternal grandfather, Neville Cooper, 91, who is also known as Hopeful Christian, is the founder and current leader of Gloriavale. For three generations, the deep-seated evangelist beliefs of his community have run in Lilia’s blood.

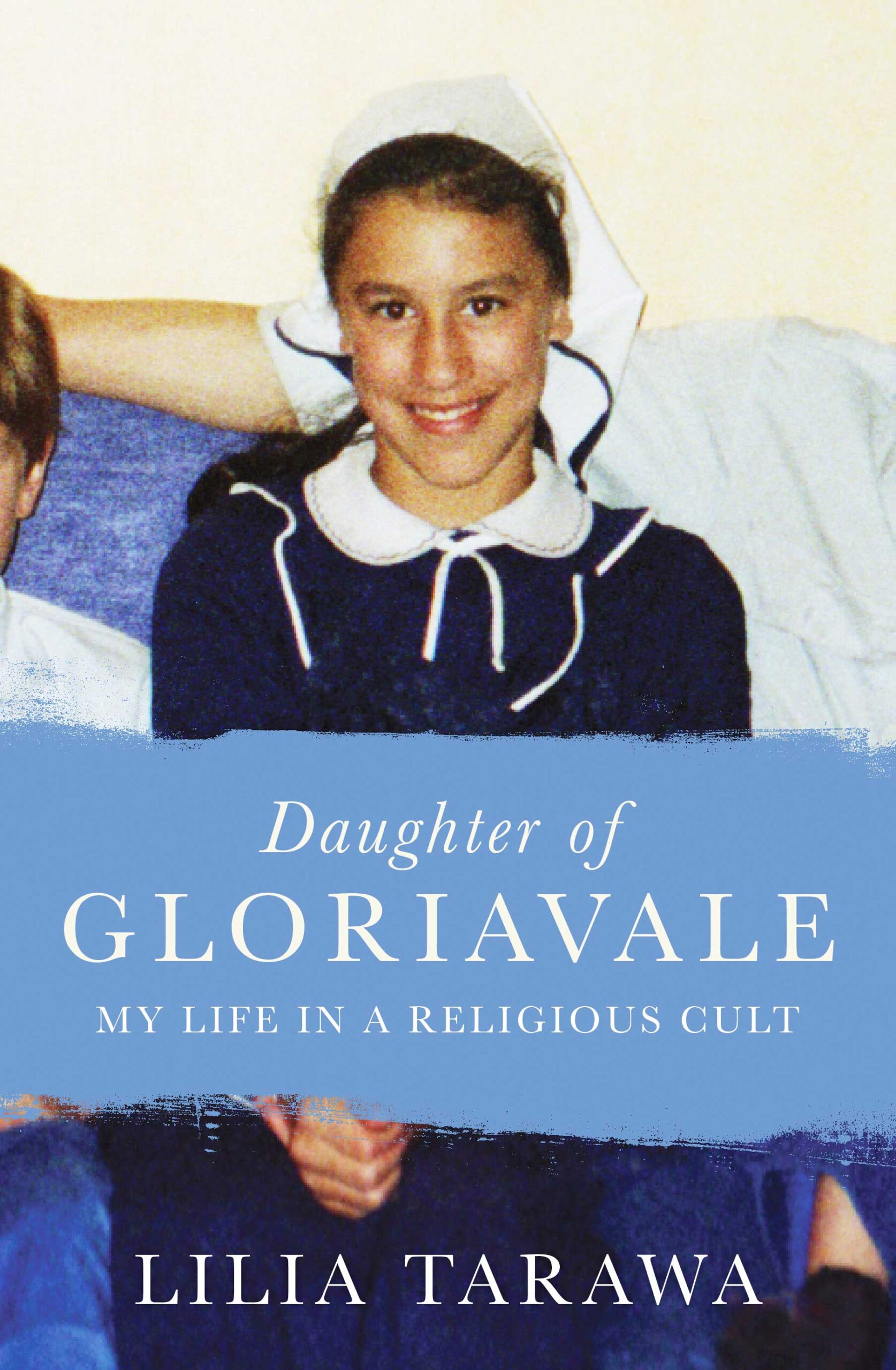

Lilia being baptised.

“For a long time, my life and everything I valued was made up of my faith in God, my relationships with people I loved, and the future ahead of me as a Gloriavale wife and mother,” she tells.

But in 2009, Lilia’s family – her father Perry, her pregnant mother Miracle and her six younger siblings – fled Gloriavale under the cover of darkness with only the clothes on their backs.

On the outside, they joined Lilia’s three other siblings, Sara, 30, Sam, 29, and Victor, 24, who had run away as teenagers. “We definitely had a rebellious gene in our family,” laughs Lilia.

Testimony to that are her siblings’ names – while most families gave devout Christian names such as Fervent Stedfast and Steady Standtrue, Perry, 53, and Miracle, 51, skirted the rules with Lilia and her younger siblings, Gloriana, 20, Asher, 17, Judah, 15, Serena, 13, Melodie, 10, and Arielle, seven.

“My father Perry was well-travelled and open-minded,” explains Lilia. “He refused to see the world the same way as the rest of the Gloriavale shepherds.”

In yellow, third from left, before a recital.

“My father Perry was well-travelled and open-minded,” explains Lilia. “He refused to see the world the same way as the rest of the Gloriavale shepherds.”

Miracle and Perry had met as children within Cooper’s sect and married young. But over time, they had become increasingly fed up with the stifling rules, and constant threats of hell fire and brimstone. Gloriavale had also been under a cloud since the 1990s, when Cooper was jailed for indecent assault.

When Lilia’s siblings ran away, her parents were told they were sinners who should be dead to them. “Leaving Gloriavale was the best thing we ever did and the only way we could all be together again as a family,” declares Lilia.

Her earliest memories are of playing in the compound’s streams, rivers and forests, with her many siblings and cousins. “They are happy memories – good, wholesome memories.”

Her mum Miracle was one of Neville Cooper’s 16 children, and would go on to have Lilia and nine others. Only the youngest, Arielle, was born outside Glorivale.

“Our dormitory floor had 105 people I was related to on it. Someone asked how many cousins lived there and I have no clue – maybe 300?” tells Lilia.

Lilia (back row, second from left) with her Gloriavale working team.

Her grandfather Cooper was a radical evangelist, arriving from Australia in the 1960s with his wife Gloria and their growing brood of children.

His vision was to set up a rural Utopia, where families could sign over their worldly possessions to serve God, and live a humble, obedient and self-sufficient life.

Lilia says her large family shared a room little bigger than a double bedroom. Children attended preschool, then school, but from the age of six they rose early to carry out domestic chores. Meals were prepared in huge commercial kitchens and each night the community of more than 500 people ate together at rows of 10-metre long tables.

Looking back, Lilia says she’s thankful for her Christian values and for the opportunity to have learned arts, crafts and music. All Gloriavale children are taught music and she is competent on the ukulele, flute, recorder and violin.

However, as Cooper’s reign continued, his rules intensified. The outside world was cut off, including access to uncensored books or music, TV, the internet, newspapers and radio.

Family and friends outside the boundary were labelled sinners and contact was banned. Babies were born on-site and medical intervention was for emergencies only.

“As a child, I thought we had a force field around us,” says Lilia with a smile. “I knew there was another world out there, but I just couldn’t grasp what it was like.”

It was her parents Perry and Miracle who decided to leave.

One of the first trips outside that she recalls was at age 10 to Greymouth to have her eyes tested. “It was exciting,” tells Lilia. “A taste of freedom.”

Although she never witnessed any sexual abuse, Lilia says her parents grew increasingly uncomfortable because of the arranged marriages and families who were ripped apart when some members chose to live life on the outside.

At Gloriavale, bathroom and bedroom doors didn’t lock, children as young as 10 attended their siblings’ births, and newly married couples were given sessions in how

to make love.

As well as that, parents were expected to rule with an iron fist in a “spare the rod, spoil the child” philosophy. Disobedient children were publicly shamed, strapped

or went without food, according to Lilia.

While her grandfather Cooper disapproved of her strong mind, he was at times loving and kind. “He would play the piano, and I would sit and listen to him. Even today the sound of the keys calm and centre me.”

One of the only mementos that Lilia has of Gloriavale is a scrapbook of letters they wrote each other when Cooper was incarcerated.

But a turning point came when she was six and Cooper humiliated her on stage for getting an A-grade report that described her as a “future leader”.

He scolded her in front of the entire community, saying that “women are meant to be meek and quiet – this is a terrible report.”

Lilia explains, “If you were not a perfect, Christian girl, you were reprimanded. That was ingrained and it took me years to realise I had low self-worth.”

After years of being told what to think, say and do, the Tarawa family at first struggled to make sense of the outside world. “The early days were exciting – but scary,” she tells. “I thought, ‘I can do anything and be anything – but who am I?’”

Lilia’s “first birthday” on the outside with new shoes.

Perry found work as a plumber and Miracle was skilled in bookkeeping, but the family moved house a lot. Lilia went flatting, but she still felt restless. “I didn’t feel like I belonged in the outside world.”

And after a lifetime of wearing a shapeless dress, buying clothes was fraught. “I had to get used to wearing clothes that showed off my legs and bum,” she remembers. “Even in jeans and a T-shirt, I felt people were judging me. I was vulnerable, like I was stripped naked.”

Lilia went to college but dropped out. She went into business with her family, but that didn’t work out either. Then about four years ago, the young woman hit rock bottom. She became physically sick and began to suffer panic attacks. Taking hold of her life, Lilia began to write each morning on the mirror in lipstick “I’m beautiful, I’m sexy, I’m talented, I’m a leader, I’m desirable.”

And for the first time, she felt ready to share the story of her life. Her book, Daughter of Gloriavale: My Life in a Religious Cult, is released this month.

Daughter of Gloriavale: My Life in a Religious Cult by Lilia Tarawa is available now, published by Allen and Unwin, rrp $36.99.

“I decided to write myself a new story, and part of it was looking at the past and talking publicly about Gloriavale for the first time without shame,” explains Lilia.

She also credits her newfound health to USANA health supplements and is involved in marketing the products. “I want to pay it forward and share my experiences to help other people make changes in their lives.”

Eight years after leaving Gloriavale, Lilia’s family has also turned a corner. The six youngest siblings still live at home with their parents in Canterbury, and are involved in kapa haka and basketball.

“We do Sunday dinners and catch up like a normal family,” she says. Although she has had relationships, Lilia is happily single. After years of helping to raise babies at Gloriavale, she has no immediate plans for marriage or a family.

“It would take someone special to rock the boat – they’d have to add serious value to my life,” she declares with a laugh.

Instead, Lilia sees for herself a future of travel, public speaking and writing another book – this time on empowerment.

She’s determining her own fate, but accepts the fabric of who she is and that she has come from Gloriavale.

“My granddad Cooper is painted as a villain, but he’s also a charismatic leader and great orator. I can never hate him because he’s made me who I am today – and for

that I am grateful.”