It was a challenge Tim Carr couldn’t refuse.

He and his partner Fay Cobbett were out walking when they began talking about the fact that Fay, a breast cancer survivor, found her prosthetic breast so uncomfortable that she’d stopped wearing it.

“I was mostly okay about going around lopsided because it was better than the alternative and Tim understood why,” recalls Fay.

“But on that day,he said he didn’t like people looking at me and making judgements without knowing why I looked like I did.

“So I said to him, ‘If you can get me something better, then I will wear it.’ And he said, ‘Okay.'”

Tim’s decision to take up Fay’s challenge has not only made a huge difference to her, but looks set to make life post-surgery much better for many other women who’ve had mastectomies.

Back at work after her mastectomy, Fay wasn’t to know the 3D machine would be the answer to her prosthetic prayers.

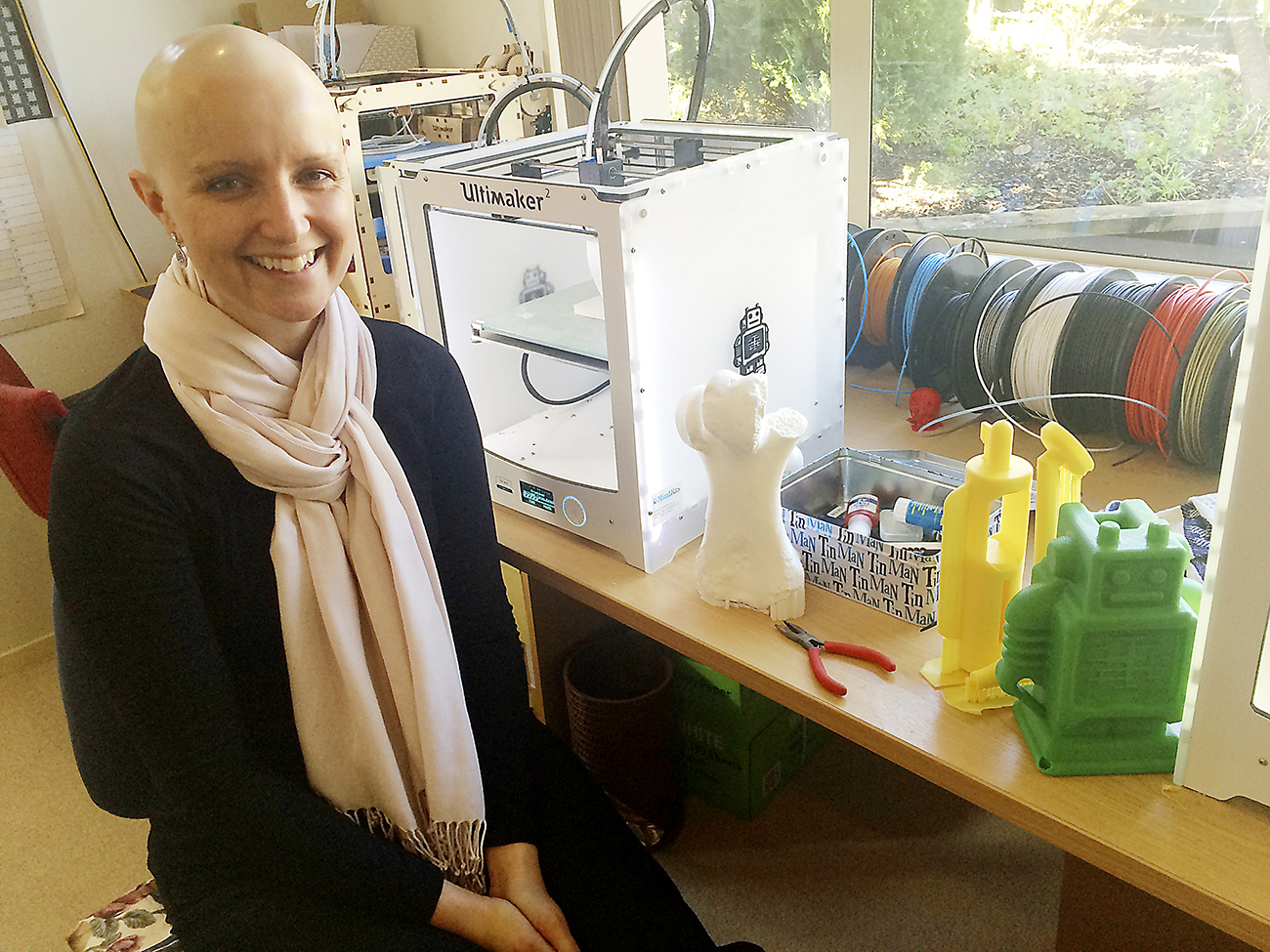

After that conversation two years ago, Tim – who runs an electronics, robotics and 3D printing company called MindKits with Fay – got together with colleague Jason Barnett to design a prosthesis tailored specifically to his partner, and made on a 3D printer.

The prosthesis they came up with is so comfortable that Fay wears it all the time and barely notices it’s there.

Fay (38) and Tim (40) have since set up a company called myReflection to make prostheses for other women, and Fay hopes they’ll get the same benefits she has.

“It’s been a huge gift for me,” tells Fay.

“After everything I went through with cancer, it’s just made life much easier.”

Aucklander Fay, who is mum to Zoe (8) and Sophie (5), was 35 when she was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2015.

She was still breastfeeding Sophie and thought the lump she could feel was a blocked duct due to mastitis. But it turned out that she had infiltrating ductal carcinoma, which had spread to her lymph nodes.

She had a lumpectomy, followed by “pretty brutal” chemotherapy. Then another operation to ensure they’d got all the cancer showed that she had a secondary breast cancer, a carcinoma in situ, which was sitting in the ducts.

“It was a nasty beast,” Fay says. “Having a full mastectomy was a no-brainer.”

That was followed by radiotherapy and, once all the treatment was over, Fay went to see a surgeon about breast reconstruction.

The radiation had taken such a toll on the skin on her chest that it wasn’t possible to create a new breast using it.

Her only option was to have major surgery that involved moving skin, muscles and fat from her abdomen or back to create a new breast, but it would have left her with massive scarring, and her body could still reject the transplanted tissue.

“I decided not to do it as I had already been through so much and it wasn’t worth it for the sake of a boob.”

3D printers can create anything from toys and household items to body parts.

The next course of action was to get a prosthesis.

Women who have had mastectomies are entitled to a $613.33 subsidy every four years to cover the cost.

“You don’t get a lot of choice – they come in different cup sizes but are a generic shape,” explains Fay.

“So they don’t necessarily match the shape of your other breast.”

The silicone inserts, which are imported from overseas, sit in a pocket in a specially-made mastectomy bra. They are very delicate and, when not being worn, have to be kept in a covered box.

Because surgery and radiotherapy meant Fay’s chest wall wasn’t flat and she was left with lymphoedema (swelling) around her scar, she found the prosthesis painful.

“It rubbed and was sore,” recalls Fay.

“And there were other issues. Because it sits in your bra, if you lean forward, it falls away from your chest wall and you are worried all the time that someone will notice. And you can’t wear certain tops in case people can see it. You also can’t wear anything close-fitting because it looks different to your other boob.

“Plus, when someone hugs you, they can feel this rock-hard lump, which is not nice. I didn’t like hugging people.”

The prosthesis also had a habit of moving out of position.

Tim says, “It would move so much, it would end up sitting on Fay’s shoulder. We had hand signals so that I could subtly

let her know it had moved and she could adjust it.”

Eventually, she’d had enough and stopped wearing it.

Faye and Time teamed up with 3D-printing whiz Jason to create an ultra comfortable breast prosthesis.

Then came the conversation during their walk.

When Tim got home, he quietly set about researching breast prostheses and the science behind them. He talked to 3D-printing whiz Jason, explaining what Fay was going through, and suggested they could work together to print something that was better than the prosthesis she had.

“The first prototype they made was blue and I said, ‘Are you trying to turn me into a Smurf?,'” Fay recalls with a laugh.

“But as soon as I put it into my bra, even though it was the wrong size for me, it was so much more comfortable.”

Tim and Jason came up with many versions. “There would be all these different breasts sitting on our table,” Fay says.

“Anyone walking in the door would have wondered, ‘Why is your table covered in boobs?’ But they stopped being breasts to them – it was all about the science and the technology.”

As well as quizzing Fay, Tim approached the Breast Cancer Foundation, who put him in touch with other patients so he could ask them about their needs.

“By this stage, I was starting to think that this might not only be able to make a difference to Fay, but lots of other women,” he explains.

“What was then available was technology that was more than 20 years old and hadn’t been updated. At best, the prostheses were functional, but many women really disliked them. They were being very stoic about it.”

Tim and Faye say the response to their prosthetics has been amazing.

One of the things he and Fay repeatedly heard was how heavy prostheses were, especially for women with bigger breasts. Some women end up with prostheses that weigh a kilo or more.

“Because it is not connected to you, it feels heavy – it’s like having two blocks of butter in your bra,” says Fay.

“We’ve met women who say they have back issues and think it is because they are carrying this unnatural amount of weight on one side.

“And there are also women who get a cushion from a craft shop, hack it up and put fishing weights in it to try to make something that is more their shape.”

Some of the breast cancer survivors reported that their prostheses were so delicate that they became easily damaged.

“There were women who had Band-Aids covering tears in theirs. We heard about one woman whose prosthesis fell out of her bra when she leaned forward, and went splat. It ended up with plasters all over it.”

And because women get a subsidy only every four years, they had to fork out if a prosthesis needed replacing earlier. Some had been advised to procure second-hand ones belonging to women who’d died.

“That’s just mind-blowing,” says Tim.

After much trial and error, he and Jason created a prosthesis that has a light and flexible inner core, coated in hard-wearing, breathable silicone that is ISO-certified to be safe for skin.

But what really made a difference was the customisation.

Fay was scanned so the prosthesis would mirror the shape of her other breast,and contour to the lumps and bumps on her skin.

“It actually wraps around my chest wall and stays there because it is made to fit my scars,” says Fay.

“It’s like a piece of a puzzle slotting into place. So you can wear a normal bra, and jump up and down, and the prosthesis stays put because it moulds to your body.”

Once they’d perfected the design, Tim and Jason worked on keeping the price down so it wasn’t something only people with big bank balances could afford.

The government subsidy covers the cost of up to four prostheses, as well as the scanning.

Currently operating in Auckland, the myReflection team hope to eventually be able to help cancer survivors nationwide.

Fay and Tim launched myReflection in February to a flurry of interest.

“We were so immersed in what we were doing that we wondered, ‘Is anyone actually going to be interested in this?'” says Tim.

“But the response has been amazing and we are excited about being able to share this with other women who’ve been through breast cancer. Hopefully, it can improve their quality of life and help to restore their self-image.”

It has certainly made a huge difference to Fay.

“I have the prosthesis in all day and don’t notice it’s there. I can wear normal lacy bras and sports bras again, and whatever tops I want. I wore a close-fitting T-shirt to the launch – I couldn’t have done that before. And I asked a room full of people if they could tell which was my real breast, and they couldn’t.”

She smiles at her partner as she says, “Tim has been amazing throughout everything I have been through in the last few years with the cancer, but for him to come up with this prosthesis… it’s definitely the best gift I’ve ever had!”

How does it work?

At the moment, scanning for Tim and Fay’s business myReflection is only available in Auckland, but will eventually be nationwide.

Breast cancer patients will be scanned in privacy either at home or at the venue of a myReflection agent, including selected Bendon stores.

The scans are then used to map out a customised prosthesis and women can have two versions printed straight away.

They can get two more under the government subsidy if those are damaged or if they change shape – if, for example, their weight changes.

Scanning involves taking a series of photos of the torso and it’s painless. Tim and Fay hope to eventually establish a breast library for women who’ve had double mastectomies – they’re hoping volunteers of different shapes and sizes will offer to get their breasts scanned so they can build up a collection of prototypes for breast cancer survivors to choose from.