Poet Sam Hunt is on the phone from his home in Kaipara. It’s a morning interview, but already he is fabulous – gracious, funny and raw. He has recently developed vertigo, he explains, but he quite likes it – the feeling of floating through the day. “Who needs drugs?” he says.

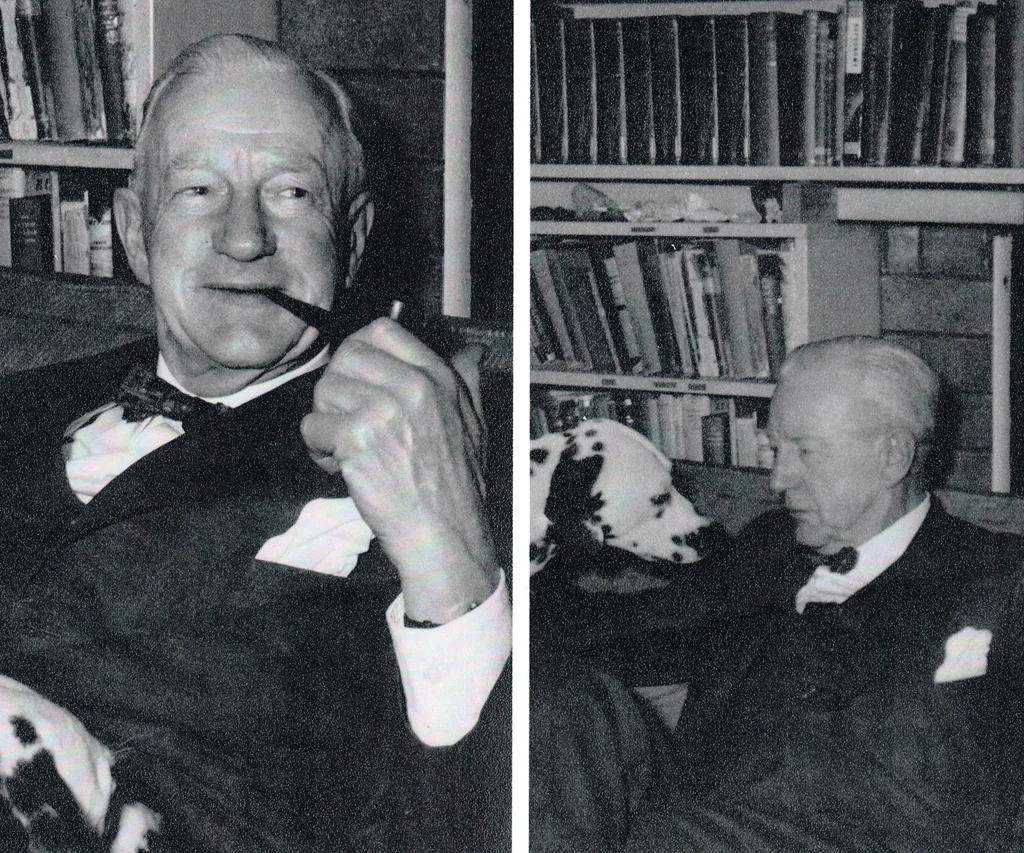

The purpose of the call is to talk about his dad for Father’s Day. Some of his most famous poems are about his father, Percival Robert Hunt, or Percy as he was more commonly known – Birth of a Son, My Father Scything and My Father Today.

His most recent written poem about his dad is My Father’s Waistcoats from his latest collection, Salt River Songs, released to coincide with Sam’s 70th birthday. The book is already, to the poet’s delight, a bestseller.

*My father’s waistcoats

never had pockets.

It was years later

someone explained

a good lawyer in court

didn’t need notes…

I never went with the law

like my father would have liked.

But I got to swing juries –

like he said – swinging the lead.

I never rode into town

like I’d like to have done.

But I carry a gun

in my head.*

Sam was wearing one of those waistcoats (with jeans and heavy boots) when Percy’s friend, former Labour MP Martyn Finlay, visited him at his Bottle Creek boatshed home, north of Wellington, in the 1970s.

“He said, ‘I see you are wearing one of Percy’s old waistcoats,’ and I said, ‘How do you know that?’ and he said, ‘No pockets.’” He went on to explain to Sam that the top barristers don’t need notes.

Top poets don’t either. “A sign of a good concert is one when you come off stage at the end of it and you haven’t referred to your notes,” Sam agrees, voice gravelly, syllables long. “You haven’t even looked at them or thought of them, it has all been happening out there in a sort of divine trance; sometimes it is a bit like that!”

He does write down the poems’ titles, in case he goes blank – but he needn’t worry. Somehow, despite his well-documented excesses, at 70 Sam Hunt is as sharp as a tack, reeling off poems with little pause – ballads his father used to tell him when he was 10, W.B. Yeats’ poems his mother shared with him when he was small.

He recognises his similarities with Percy Hunt – it was from him that Sam inherited the ability to command a room and an audience.

“Yes, I say in that poem, ‘I never got into the law as my father would have liked’ because I was quite attracted to it. I would go out there in the court, and my old Dad would be there with his wig on bamboozling the jury, and so I see a lot of parallels.”

It is this strength of presence (as well as his father’s six-foot-two height) that led Sam to describe Percy in My Father Today as a ‘heavy load’ and his weight in Birth of a Son as a ‘bloody ton’. That and the convenience. “I used ‘heavy load’ in My Father Today because it rhymed with road,” he says of the 1977 poem about his father’s death.

*They buried him today

up Schnapper Rock Road,

my father in cold clay.

A heavy south wind towed

the drape of light away.

Friends, men met on the road,

stood round in that dumb way

men stand when lost for words.

There was nothing to say.

I heard the bitchy chords

of magpies in an old-man

pine… ‘My old man, he’s worlds

away – call it Heaven –

no men so elegantly

dressed. His last afternoon,

staring out to sea,

he nods off in his chair.

He wonders what the

yelling’s all about up there.

They just about explode!

And now, these magpies here

up Schnapper Rock Road…’

They buried him in clay.

He was a heavy load,

my dead father today.*

Percy was 60 years old when Sam was born; a reality which Sam admits came with some difficulties. “He was an older father. When I was 10, he was 70. That’s the age I am now and the thought of having a 10-year-old would be quite hard work, but Dad coped with it quite well. But when I was in my 20s and 30s, he was in his 80s and 90s and that was the time he was losing it.”

It is that sense of absence he describes in Birth of a Son.

*My father died nine months before

My first son, Tom, was born:

Those nine months when my woman bore

Our child in her womb, my dad

Kept me awake until the dawn

He did not like it dead.

Those dreams of him his crying

‘Please let me out love let me go!’

And then again of his dying…

I am a man who lives each breath

Until the next: not much I know

Of life or death; life-after-death:

Except to say, that when this son

Was born into my arms, his weight

Was my old man’s, a bloody ton:

A moment there – it could not stay –

I held them both, then worth the wait,

Content long last, my father moved away*

In My Father Scything Sam has expressed that loss once again in the line “he wasn’t around when I wanted him most”.

“He was quite hurt by that poem,” Sam says. “I don’t know really what I meant by that line, but I think I was really expressing the wish that we had had more communication over those last 10 years [of his life].”

Sam’s mother Joan was 30 years younger than Percy. “They were quite an unusual couple – the age difference for a start. They both had a great love of words, coming from different backgrounds – my mother from a more literary background, and my father from a more musical background. His father and brother were professional musicians.”

And while it was his mother’s choice in poetry that attracted Sam most, he loved the ballads his father told him. “Like Lord Ullin’s Daughter – great stuff,” he says, reeling off the ballad flawlessly.

“Those are the sort of poems I got from my Dad. My mother’s taste in poetry was probably more aesthetic I guess, more lyrical, and that includes poets like W. B. Yeats, and I in turn introduced her to a lot of poems, and so there were a lot of poems being told.”

But he is quick to clarify: “It was poems, not poetry with a capital P that you study in school and have to answer questions about – it was sheer pleasure in the poems.”

While Percy supported Sam’s poetry, he was concerned his son didn’t have a fall-back, and would routinely send him five-pound notes in the mail.

To allay his concerns, Sam went to teacher’s training college. He completed the course, but by the time he had finished, he was already making money from his poetry.

Percy died at the ripe old age of 90, a fact Sam links to his habit of swimming daily in the sea. “In his younger years he developed sciatica. He had a manservant, his name was Cassels, who did a lot of the things that a PA would do now.

Cassels was a fitness freak and he had a regimen for Dad so that he could keep the sciatica at bay, which included swimming in the sea every day.

“When Dad was a young lawyer he was living in a stone house in the quite smart city suburb of Parnell and he literally swapped it for this big rambling property on Milford Beach, which is where I grew up. A couple of times, at least, on the shortest day of the year they had a photograph in the Auckland morning paper of Auckland barrister Percy Hunt emerging from the waves, like Venus – well, not quite like Venus… I wish I had those photos.”

Sam shares his father’s love of the water, and has continued to reside near it in his adult years. He remembers particularly well one trip home on the ferry from Auckland to Castor Bay with his smartly dressed and proud father.

“It was before they had the Auckland Harbour Bridge, so I would have been five. Dad used to like to jump off the ferry as he came onto the wharf so he could get the best seat on the bus. On this occasion Dad did this and missed his footing and he went straight down into the water. The crew on the ferry got him out of the water so quickly he was barely even wet, and as we walked toward the bus he said, ‘I didn’t fall in the water did I?’ And I said, ‘No, you didn’t fall in the water.’ Because Percy Hunt wouldn’t do that, no.”

His father’s Auckland chambers were in the Town Hall and Sam recalls the joy of attending concerts downstairs together. “In fact, from my father’s office you could go through these catacombs with great piles of legal notes and old law books going up to the ceiling and make your way through to the backstage of the Auckland Town Hall. Once we were going to a bloody marvellous concert by the French cellist Pierre Fournier, who that evening was playing the Dvorak cello concerto with the then National Orchestra, and I came up out through the cupboard and old Pierre Fournier was practising in his backstage room.

“I said, ‘I wasn’t trying to get in for nothing, we’ve got tickets, I am just waiting for my father. He’ll be down by eight o’clock,’ and he said, ‘That’s fine; I hope you enjoy the show.’ It was lovely. I went back to my father and said, ‘I have just met Pierre Fournier’ – he said, “What?!” Sam recalls, laughing heartily. “He was quite impressed.”

Once Sam started touring his poems, his dad was in an old folks’ home and, when in Auckland, Sam would visit him. One visit in particular stands out.

“I did a tour in 1975 with three other poets – Hone Tuwhare, Denis Glover and Alan Brunton. It was good, a very successful tour – the final night was in what was called the Mercury Theatre. In the morning there was a big front-page photo of me on stage at the Mercury.

“I went to see Dad the next day and a nurse had pinned it up beside his bed. He was very feeble at that stage, very absent, and I got permission to take him out in my old ambulance; I had a mattress in the back so he could sit up and we drove it to Milford Beach and parked up and drank a bottle of whisky. We had a great time.”

We have five copies of Salt River Songs, by Sam Hunt to give away. To enter the draw, email [email protected] by September 7, 2016, subject: ‘Sam Hunt’.