Bank robber-turned-bush lawyer Arthur Taylor spent nearly 40 years in prison, but it didn’t stop him marrying his sweetheart, infamously fathering a child from behind bars and later proposing to a Canadian law student half his age.

Yet while there’s been no shortage of women in Arthur’s life, it was his little sister Joanne Ashby who was there to greet him when the prison gates finally opened. After being denied parole 19 times, Arthur, now aged 62, was finally released from Waikeria Prison in February.

“As much as Arthur has done the time all these years, I’ve done it alongside him,” says Jo, 49, mother to Marc, 29, Taryn, 27, Chase, 17, Blade, 11, and grandmother to five. Over the last four decades, Jo has visited her big brother “Boy” or “B” each week, run his affairs in the outside world and talked to him by phone up to four or five times a day.

Arthur adored Jo from the time she was born.

“My son Blade was three days old the first time I took him into Paremoremo,” Jo tells. “A lot of women talked about being there for you, B, but I always knew it was me you were coming home to,” she tells her brother firmly.

“Yeah, I’d thought about that day for a long time, but when I got out, the first thing I did was get you to drive me to the dairy to buy a ham roll – best food I’d eaten in years,” replies Arthur, who says he put on 21kg inside from the high-carb prison diet. He still keeps a sachet of garish-pink prison jam in the fridge as a reminder of his past.

Thirteen years apart, Arthur and Jo grew up the eldest and youngest of six kids in a law-abiding, hard- working yet raucous family headed by their late parents, stoic Arthur Taylor senior and his formidable Catholic wife Shirley. They are close with their other siblings, Sandra, 61, Diane, 59, Shirley, 58, and Johnny, 54, but have always shared a special bond.

“Our relationship has always been unexplainable,” says Jo. “We can communicate with just a look, like we’re telepathic – we don’t need words, aye B. And it’s got stronger year by year.”

The afternoon Woman’s Day visits, Jo and Arthur are in the kitchen of her remote farmhouse in the shadow of the Kaimai Ranges, reminiscing about the past. Their chatter is noisy and punctuated by loud laughter. This is where Jo took Arthur when he was first released, to be greeted by a homemade “Welcome Home” banner and many of his siblings, scores of nieces and nephews.

“Yeah, we did have a few drinks to celebrate,” says Jo. “And remember B, we played that song, ‘Tie a Yellow Ribbon Around the Old Oak Tree’, like Mum used to every time you came home.”

Arthur’s early childhood was spent on a farm in Waiotemarama, a remote region of the Hokianga in Northland. It was there the Maori community gave him the nicknames “Boy”, “Butch” or “B”, which those closest to him still use today.

Arthur was a bright child, but easily bored. His school reports at 11 put his reading age at 18 and his family says he’s always had a photographic memory. Years later, he joined MENSA, a global organisation for people scoring in the top 98th percentile of a standardised IQ test.

When he was a youngster, the Taylor family moved to the Wairarapa, where his parents worked long hours running a dairy on Queen Street in Masterton. Arthur began to bunk school, preferring to read in the local library or working in the dairy. “I was always hard-working, entrepreneurial. I had a big tin of cash,” he laughs.

When he was 13, Jo was born. “She had lots of black hair and was the most beautiful baby,” reminisces Arthur. “I remember I just picked her up, cuddled her and didn’t want to put her down.”

About the time Jo joined the family, the state caught up with the teenage truant and Arthur was incarcerated for the first time at the infamous Epuni Boys Home in Lower Hutt.

“I still remember a doctor with a syringe chasing me around the dairy, trying to sedate me and take me away,” claims Arthur. “My parents were devastated, but in those days, the state knew best.”

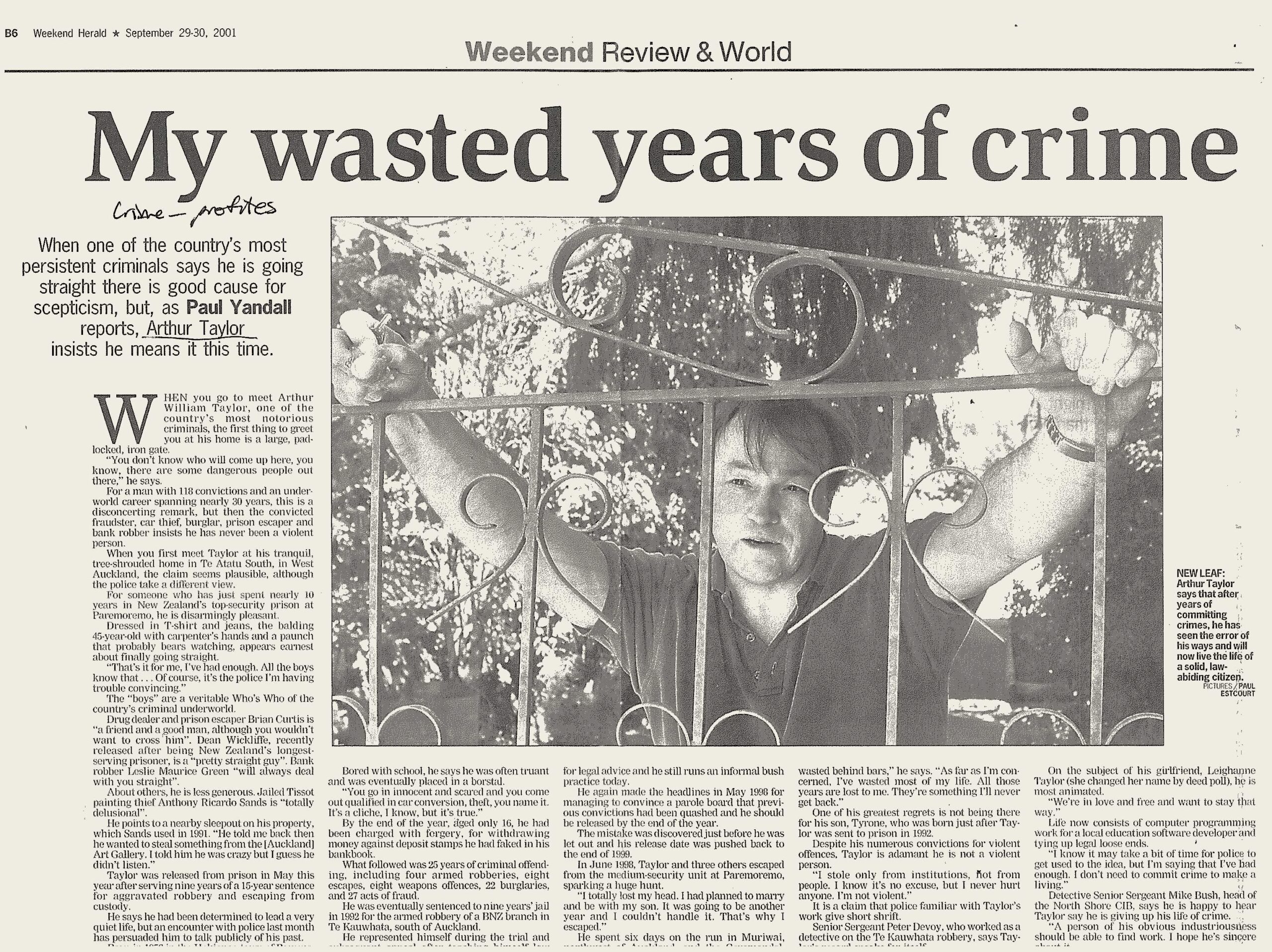

Arthur in 1997.

Jo’s first memories of her big brother were sitting in the back of the family’s black Humber Super Snipe, making the slow and winding trip over the Rimutakas to visit him in Epuni.

“Every weekend like clockwork, Mum and Dad visited, and because I was the baby, I always tagged along,” recalls Jo.

Arthur would run away and each time end up in a more secure unit. “Looking back, that’s where I learned most of my tricks of the criminal trade,” he says.

He was still in his teens when he racked up his first conviction for forgery and graduated to Mt Crawford Prison.

“I still remember the big white door,” quips Jo. “As a child, I loved it because I thought I was coming to see you in a castle. Most people freak out with court and prisons, but for me, it’s normal. I’ve been visiting B in prison all my life.”

Home for good! Arthur with (clockwise from left) a family friend, Jo, Taryn, Chase, Tiana, Blade and Tristin.

And at 17, Jo was visiting Arthur in D-Block at Paremoremo when the teen caught the eye of fellow inmate Brett Ashby.

“You always told me B, ‘Don’t look at anyone,’ but Brett spotted me,” says Jo.

The pair later married and had a child together, Jo’s youngest, Blade. Brett died of cancer in 2009 before he could be put on trial for the execution-style killing of methamphetamine cook Grant “Granite” Adams.

Jo staunchly defends her late husband, just as she does her big brother. “If anyone touches my brother, I’m like a pit-bull – it’s all on.”

On more than one occasion, Jo’s been compared to Cheryl West, the criminal matriarch on local TV show Outrageous Fortune – and she doesn’t mind one bit. “Arthur has told me since I was a child, know your rights and know how to fight,” she says.

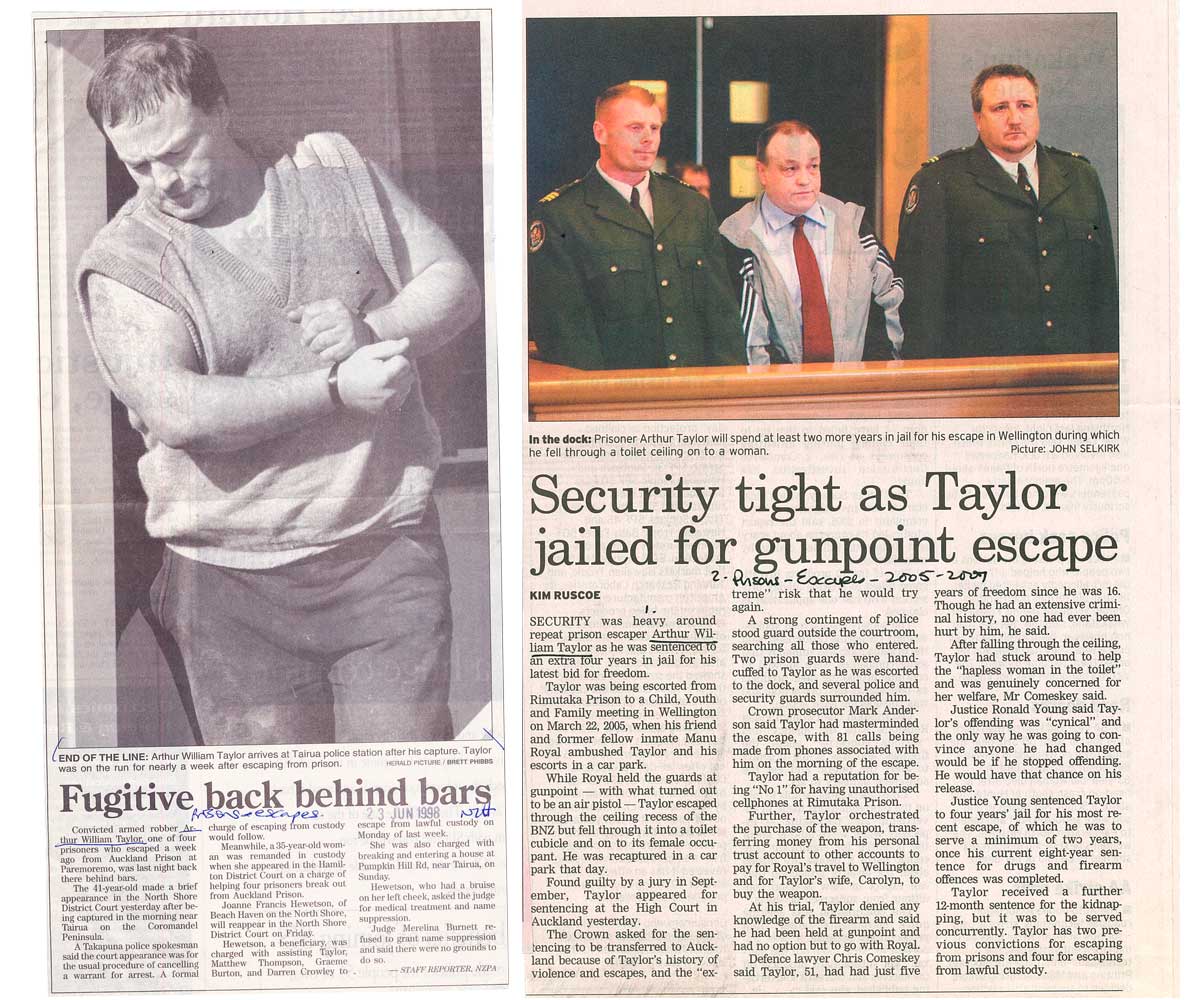

Arthur’s family in 1992 (from left) Jo, dad Arthur, mum Shirley, John, Shirley and Diane.

In the kitchen of Jo’s farmhouse, brother and sister trade stories about Arthur’s life-long merry-go-round of crimes, court appearances, prison lags and daring escapes.

There’s the story about him falling off a nine-metre cliff in the Coromandel with a police helicopter circling overhead, breaking into a millionaire’s wine cellar, and falling onto a woman’s lap in a toilet cubicle while trying to escape through an air conditioning duct. “I stopped to ask if she needed a doctor and that’s the reason I got caught,” bellows Arthur.

“The funny thing is, I never planned a life of crime. After a while, I just began playing games with the police – it was a game of wits.”

Now finally free, he’s determined to stay on the right side of the law and put his talents to use helping others as a legal advocate, human rights campaigner and advocate for the decriminalisation of cannabis.

Since Arthur’s been out, his phone has rung hot with people asking for his help and in four short months, he’s given a speech to the Privacy Commissioner and attended a four-day conference on penal reform, rubbing shoulders with lawyers and judges.

“What feels bloody good is walking into court through the front door, instead of coming up from the cells,” he admits.

Arthur’s parole conditions mean he lives in Dunedin, but he sees as much of Jo as he can and the pair speak daily on the phone. Both of them are still getting used to him being on the outside.

“It’s the wide open skies that take a while,” says Arthur. “I have an outdoor spa at home and when I sit in it under the stars, I can’t believe the silence.”

Jo’s having to get used to not having to rely on the phone as their lifeline. “I still go into the garden and think I must take the phone in case B calls,” she laughs.

Although Arthur’s engagement last year fell through, he says he has a number of female friends.

Protective little sister Jo interrupts, “You’re single, B, and it’s staying that way unless you run them through me first!”

The pair are looking forward to Jo’s 50th birthday later this month, which will be the first time all six Taylor siblings have gathered under one roof since 1972. Arthur has missed countless birthdays, weddings and even his beloved mum Shirley’s funeral, so now is the time to try and make up for it.

“It’s all about family – it’s been Jo that’s got me through all these years,” insists Arthur.

Adds his baby sister with a smile, “And because of you, B, I’m fierce and strong. As everyone tells me, I’m just a product of my brother.”

Who is Arthur Taylor?

He’s been called a dangerous crook, a criminal mastermind and affable villain. Arguably New Zealand’s most high-profile career crim, at last count Arthur had racked up 152 convictions, including unlawful possession of firearms, aggravated robbery, theft and burglary.

He’s escaped custody 12 times, including busting out of maximum security Paremoremo Prison in 1998 and leading police on a chase across the Coromandel, only to be found holed up in a mansion. In 2005, he again escaped and fell through a ceiling panel and into a toilet cubicle in central Wellington.

For decades, he’s been a thorn in the side of the police and corrections – and a massive security risk, travelling from prison to his court appearances with an entourage of armed guards, escort vehicles and hovering helicopters.

He had legal training in the ’80s and considered Law School at the University of Otago when he was released – but now considers he knows enough to make a difference. Inside, he taught fellow inmates how to read and write, and helped them with their legal briefs.

In recent years, he’s become a prisoners’ rights litigant, taking on the Police, Corrections, the Human Rights Tribunal and even former Prime Minister Sir John Key.

His battles have gone all the way to the Supreme Court and he’s seen success in the right for prisoners to vote and to smoke. In 2016, he successfully brought a private prosecution for perjury against Secret Witness C, who testified against David Tamihere, leading to his conviction for the murders of Swedish tourists Urban Hoglin and Heidi Paakkonen in 1989.

Arthur funds his ventures largely from his advocacy work and through his many settlements, and in 2009 (from behind bars) the IRD put his income at more than $100,000 a year.