The morning of December 15, 2014 began like any other.

The air was warm and Sydney’s financial district was decorated with red and green banners. Christmas was only 10 days away. The city was humming in anticipation of the festive break.

Among the workers and busy shoppers were Louisa Hope and her mother, Robin, in town for a meeting.

Four days prior, Louisa had been in Dallas, Texas, and was considering extending her stay, but her mother was dealing with a legal matter.

“So I came home early,” she recalls.

They debated whether to have breakfast at their hotel or go out, and decided they’d eat at the Lindt Café. It was a decision that would change the course of their lives.

Earlier that morning, a dangerous and deluded man named Man Haron Monis had also entered the Lindt Café.

He sat in wait, watching as customers came and went. As Louisa, then 52, and Robin, 73, finished their breakfast, Monis gave café manager Tori Johnson a note that said Australia was under attack from Islamic State.

The doors were locked, sealing 10 customers and eight staff members inside.

What followed was described by then NSW coroner Michael Barnes as “terror that is hard to imagine”.

Monis stood, raised a sawn-off shotgun and said he had a bomb. Distressed hostages stood at windows, holding up black flags bearing an Islamic creed.

Monis told Louisa she was his secretary and ordered her to dial Australia’s emergency number.

He wanted to speak with then Prime Minister Tony Abbott, and he wanted the ABC to broadcast his demands. Louisa was flustered and Monis grew impatient.

He told another hostage, Jarrod Morton-Hoffman, to call radio station 2GB and the emergency number.

Then he pointed his gun at Louisa and said the police had two minutes to retreat or he would execute her.

“In the café you swing from: ‘It’s all going to be okay – we’re all going to get out of here,’ to ‘Oh my God, we’re all going to die,'” Louisa says in her gentle voice.

She smiles bravely as she recounts the day.

She is a kind woman with a strong Christian faith, a quick wit, a penchant for floral dresses and an eclectic collection of earrings. It was her faith that kept her strong through the ordeal, she says.

But as Monis trained the muzzle of his shotgun on her, the terror was only beginning.

Monis would hold 18 people at gunpoint for almost 17 hours.

It was an intensely dangerous situation, the coroner said, and “could fairly be described as torture”.

The Hopes were unique among the 18 hostages in that they spent the day facing the possibility of not only their own violent deaths, but the death of a loved one.

“He was not mad in that he absolutely was in control and knew what he was doing,” Louisa says. She closes her eyes, her eyelashes gently fluttering as she relives it.

“He definitely had crossed the line within his own humanity. The violence in his heart was definitely the primary leader in his life.”

The Lindt Café siege rocked the nation, floral tributes to the victims filled Martin Place.

(Image: Getty Images)As the morning wore on, tactical response groups, snipers and police negotiators took positions.

Hostage and café worker Fiona Ma held up a sign that read: “Leave or he will kill us all. Please go.”

The gunman allowed the captives food, water and toilet breaks but he also made aggressive threats and pointed his weapon at them. He had bursts of rage.

“Although at times Monis purported to engage in acts of kindness, those acts were at best self-serving or at worst highly manipulative extensions of his cruelty,” the coroner said.

Around 3.30pm, three hostages escaped. John O’Brien, Stefan Balafoutis and Paolo Vassallo ran to safety.

Enraged, Monis warned those inside the café that for every person who attempted to escape he’d kill a remaining hostage.

Later, April Bae and Elly Chen made a desperate dash out the foyer door. When Monis heard news reports that two more hostages had fled, his anger was explosive.

As the day drew to a close, and darkness crept in, Monis became tenser and more erratic. He exhibited a particular hatred towards the café manager Tori Johnson.

The foyer door was still unlocked and escape was on the minds of many remaining hostages, but Louisa, who has multiple sclerosis, knew that she and her mother would have to stay until the end.

After the second escape, Tori moved closer to Robin.

“What he was doing was calming Mum because Mum was getting angsty,” Louisa says.

“Tori, very graciously, sat next to her.”

Louisa could hear them talking and incredibly, laughing a little, as they comforted each other.

“Tori,” Louisa closes her eyes again. “My God. Heroic. People have no idea.”

At 11pm Monis encouraged the hostages to contact their families. Log notes show negotiators regarded this as a “finality thing”.

When there was a noise from the kitchen, Monis leapt up to investigate. He took three hostages to act as human shields.

While he was gone, there was a third and final escape. Jarrod Morton-Hoffman, Puspendu Ghosh, Joel Herat, Harriette Denny, Viswakanth Ankireddy and Julie Taylor slipped out the foyer door.

Louisa says she discussed this moment many times with her mother, who has since passed away. Robin told Tori to leave but he didn’t.

“Tori was in that room still because he was trying to look after my mother, which is beyond heroic,” Louisa explains.

“Our family owes a debt to his family.”

As the six hostages rushed out into Martin Place, a glass item was knocked over. The crash brought Monis running back into the café and he fired a shot at the escapees.

Glass rained down on Julie Taylor as she fled.

Only six hostages remained.

Paramedics remove an injured person from the scence

(Image: Getty Images)Police commanders were scrambling.

They had an emergency plan in place, but the trigger was the death or serious injury of a hostage. Monis had fired, but not hit anyone.

The police held their breath. They still believed he had a bomb, although that was later proved a bluff.

Inside the café, he grabbed Louisa by her clothes and hauled her to her feet. He directed Robin to stand next to her daughter and told Tori to kneel with his hands behind his head.

“I thought: ‘This is it, he’s going to do it,'” says Louisa.

“At the same time I was thinking: ‘Is there anything I can do?'”

Monis fired a shot into the corner of the room. He fired a second shot and Tori fell to the ground.

“Even when it happened, I kept thinking: ‘Maybe he’s just shot him in the back and Tori’s gone forward’, but I knew that he was dead.”

For 17 torturous hours, Louisa had been bracing for certain death, when a flash of light, the shouts of police, a deadly eruption of smoke and gunfire brought the siege to an end.

Police smashed their way into the café.

As shrapnel ricocheted off polished granite, she believed she was about to die.

A police officer grabbed her but she couldn’t run. A bullet had blown a hole in her foot. She still doesn’t know how it happened.

“Can you hop?” She nodded and made for the exit.

Outside, on the footpath, Louisa realised that she had survived.

The pain in her foot was sharp and nasty but the pain in her soul was worse.

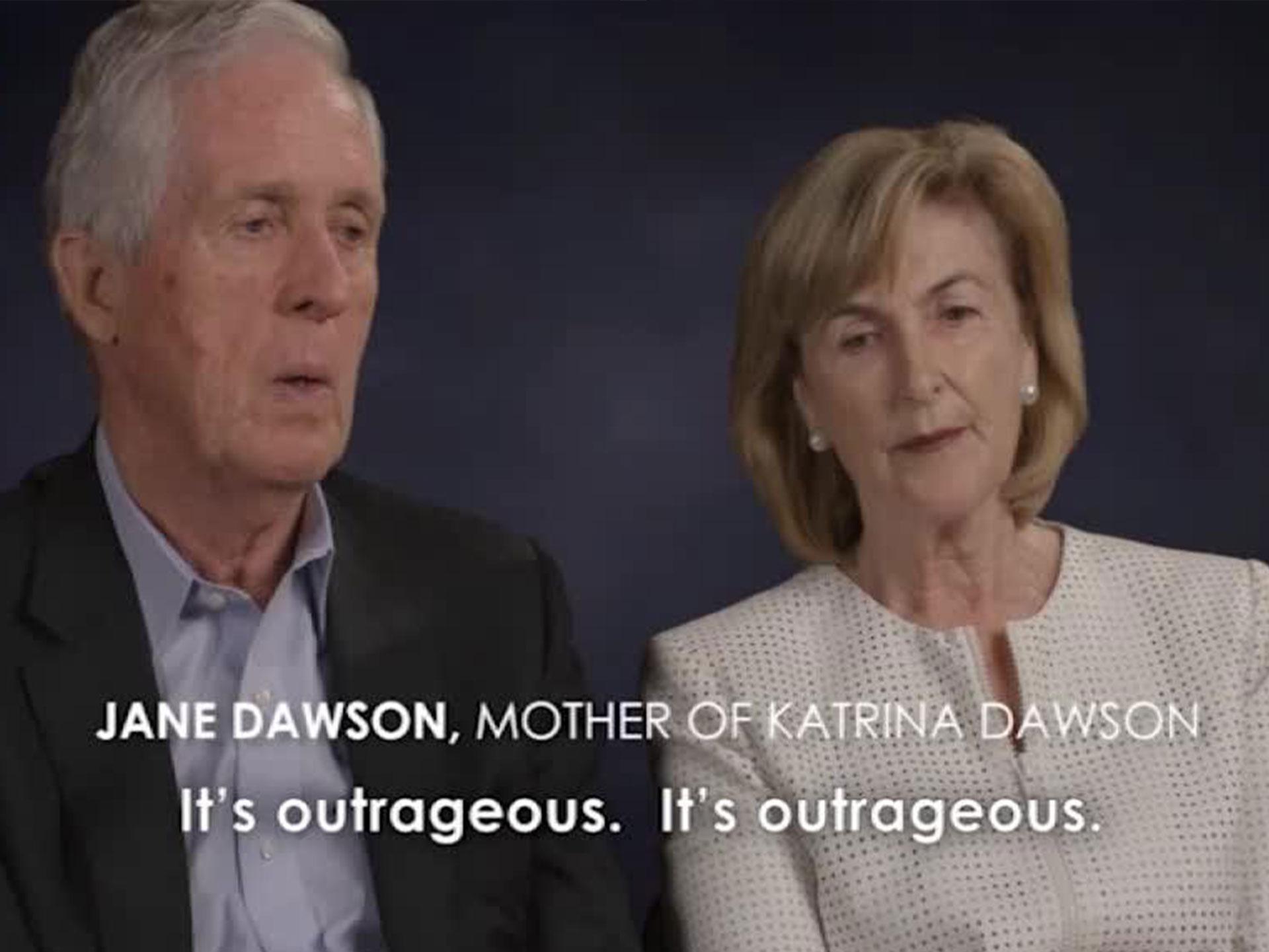

Tori, 34, was sincerely loved by his co-workers and treasured by his family and friends. Katrina Dawson, who was also killed, had an impressive career as a lawyer and a volunteer. But she was so much more than the sum of her achievements to her three small children and her heartbroken family.

Louisa’s mother was in the RPA emergency department as medical teams frantically worked to save Katrina.

“They were working and working. When they finally stopped, she could hear them sobbing,” Louisa says.

She lives with it still – the grief, the shock, the anger and relief, and the thought that saved her in the end, the thought she had as she was lying on the footpath outside the café: some good must come of this.

Her experience during the siege left an indelible mark on Louisa (seen here arriving at the inquest).

In the minutes and hours that followed, a million other thoughts flew through Louisa’s mind.

“I was thinking: ‘I’m sure I’m going to lose my foot. My mum must be dead. How am I going to tell my family that Mum’s been killed?’ I was going through all those sorts of scenarios.”

As she called out for her mother, Louisa’s mind cycled through fear, gratitude and grief. But amid it all was the idea of “turning the wickedness around”.

It felt like a lifeline as she waited for what would come next. Emergency service workers were rushing around her and she still didn’t know if her mother had made it out alive.

Paramedics lifted her into the ambulance and someone gave an assurance: “We’ve got her! We’ve got your mum.”

Tears welled in Louisa’s eyes. “And I thought: ‘But what state is she in?'”

Louisa and Robin were rushed to hospitals on different sides of the city, but were able to speak on the phone.

“It was such a relief,” Louisa says. “We both had that same sense of: I thought you were dead.”

Despite this contact, Louisa remained frantic with grief and fear.

The nurses worked quickly, cutting off her clothes and examining her wounds. Shrapnel was found in her stomach and her foot was ablaze with pain.

She asked if surgeons would have to amputate and the nurse replied calmly and with compassion: “Nah, I’ve seen worse.”

Louisa smiles at the memory and the sense of relief.

“She was able to confidently reassure me, without actually telling me, that it was going to be okay. That’s the gift of a nurse.”

Nonetheless the physical and psychological scars were deep and the following three months were a rough road to recovery.

Along the way, Louisa’s nurses kept her spirits up. They became her friends, her confidants and her comfort. She felt she could tell them things she couldn’t tell even her family.

“They’re just absorbing all of that and being, not only excellent clinical experts, but also bringing the comfort of a kind of friendship.”

Their devotion helped Louisa clarify her wish to find some good in the tragedy.

In the aftermath of the siege Louisa was paid $25,000 to appear on television. She had been thinking about holding a fundraiser with her church and friends, but after receiving the fee, she realised she could do so much more.

With Lulu, Louisa has channelled her pain into something positive.

As her time in hospital drew to an end, she visited a woman named Leanne Zalapa to discuss establishing a fund for nurses.

Leanne, who goes by Lulu, heads up the Prince of Wales Hospital Foundation, which she founded in 2004.

A nurse herself, Lulu had long been agitating for a scholarship to support nurses but had always been told there was no money.

When Louisa came into her office, still in a wheelchair, Lulu knew she had found a kindred spirit. The nursing community was in desperate need of support, and

here was someone offering to provide it.

Then NSW Premier Mike Baird matched Louisa’s initial offering of $25,000, allowing Lulu and Louisa to establish The Louisa Hope Fund for Nurses in May 2015.

Lulu, whose work saw the Prince of Wales Hospital Fund grow from a one-woman operation to an organisation of 14 staff, set up the new foundation in such a way that it would continue to grow in perpetuity.

To date it has provided $350,000 worth of grants which nurses have spent on research, equipment and education, including leadership training, a programme to get joint-replacement patients home faster, a sorely-needed welfare app for nurses, as well as initiatives to give nurses the emotional support they desperately need.

The value of the emotional support the fund has afforded cannot be understated.

“It’s that recognition that it’s a difficult job, that it takes a toll. It gives permission to the nurses to express how they’re feeling. Traditionally nurses have very much viewed that as a sign of weakness,” says orthopaedic clinical nurse, Lisa Nealon.

“A couple of years ago, I was assaulted by a patient on the ward quite badly… and there was no support,” she adds.

Louisa’s fund has helped change that.

Lulu, now 67, began nursing at 16 and says it was a tough vocation with no recognition or support.

“There was no compassion. There was none whatsoever,” she insists.

Meeting Louisa, she says, has been a gift. But for Louisa, it’s the opportunity to give back through the nursing community that has been the true gift.

“I now understand that the good that I was looking for is going to come from the nurses,” Louisa says.

“If they’d wanted an espresso machine or a popcorn maker, I would have been happy with that, but of course nurses aren’t like that. They want what’s best for the patient.”

Through their grant applications, the nurses direct how the funds are spent and “they will produce something that will be universally beneficial”.

Louisa firmly believes that what is needed after an event like the terror wrought in the café is an act of universal healing.

“Without a doubt, the siege happened to all of us,” she says.

“So we all can participate in the recovery.”

Nurses such as Karen Tuqiri (left) and Lisa Nealon (right) say Louisa and Lulu have created something very special.

Six years after one of the darkest days of recent history, Louisa is beginning to feel like herself again.

Despite what she has endured, she is the picture of grace.

She walks with a cane, her injured foot is bandaged, but if the siege has made things harder physically, it hasn’t hindered her burning desire to help those around her. That sense of purpose is an important part of her recovery.

“The siege just didn’t stop after 17 hours,” she says.

“It went on and on and on. It’s only in the last 12 to 18 months that I’ve surfaced from the event and am progressing onto more positive and happy things.”

Her work with the Louisa Hope Fund for Nurses has been a “beautiful distraction”, she adds.

“The siege has certainly left me with rattles and little chinks along the way. There’s no pretending that there aren’t holes in my heart,” she says.

“It’s the nature of trauma and how it continues to visit you. There are moments when I find it’s overwhelming. But you have to come back to your core. The core of me is not defined by the circumstance I found myself in.”

She makes conscious choices about where she focuses her energy now.

“For me, that’s faith, and faith prompts you to have hope, and hope pushes you to look for the positive things in the future.”

“She’s a remarkable woman,” Lulu says of Louisa.

“To have gone through all of that and to have come out with such generosity, spirituality and kindness, and say: ‘I want to do something.’ It was really a powerful thing to do.”

In the face of such praise Louisa is philosophical.

“Life gives you certain things, the good and the bad. This was my place in time and what I do with it is my responsibility,” she says.

“Because that bad thing happened, we turned it into this.”

To support the Louisa Hope Fund for Nurses visit powhf.org.au