The airport terminal was packed but I managed to find a seat and settled in to wait. The woman next to me looked exhausted; she’d just come off an overnight flight from the States and was heading home to Invercargill. We got talking. It turned out she is an international rugby coach and recruiter, obviously a pretty high-powered one. She asked what I did.

“Have you ever interviewed any women rugby players?” she said. No, I hadn’t.

“You need to talk to Ruby Tui,” she told me firmly. “I’ll put you in touch.”

And with that her flight was called and she was gone. The coach was Mere Baker. She’s a force to be reckoned with and a woman of her word. Not long afterwards I found myself in Tauranga talking to Ruby.

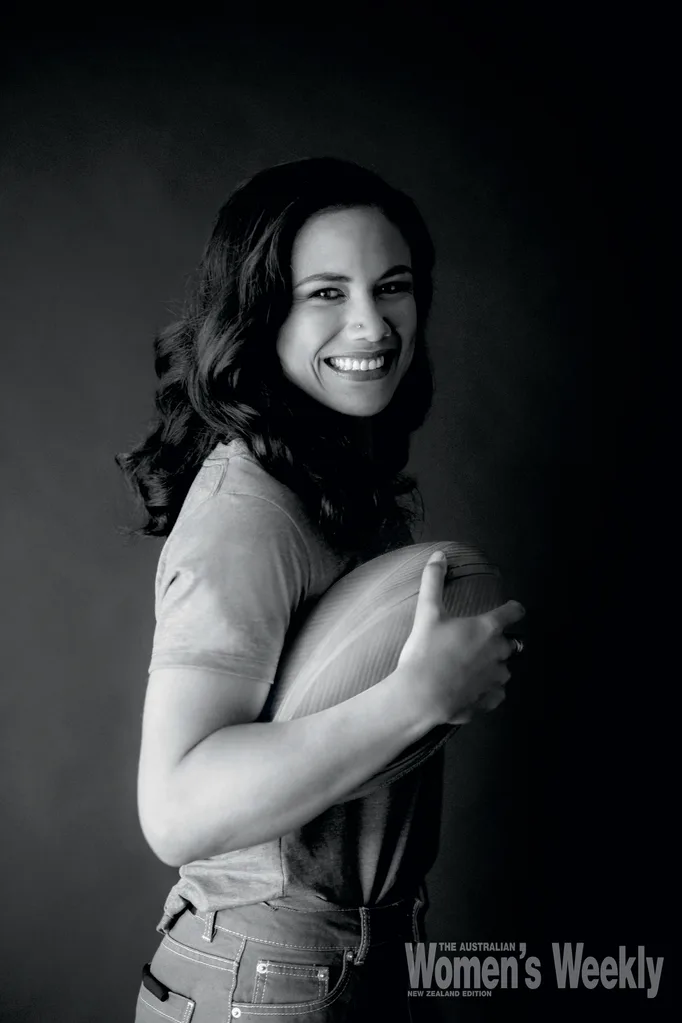

Ruby Tui is part of that dazzling squad of women rugby players that blitzed the field in the recent Rugby World Cup Sevens competition in San Francisco. She’s described as a powerful, aggressive prop.

In my ignorance of all things sport I was expecting a tall, muscle-bound woman; she is, in fact, like a finely-honed racehorse – slender, medium height, not an ounce of fat, all power and competitive fire.

The Black Ferns Sevens, like their 15-aside sisters, have captivated the world with their free-flowing style and obvious joy in the game. One of Alan Bunting’s first moves when he took over as Sevens coach was to bring six of his senior players together to be his leadership team.

“I think that’s genius,” Ruby tells me enthusiastically. “He is transparent, he listens.”

Ruby is one of the key drivers of the team culture. She talks about their failure to bring home a gold medal at the Rio Olympics.

“We lost the joy at the Olympics… we were entirely focused on bringing home gold. Now (after a change of coach) we are focused on culture. We play because we love it and we love each other.

“I got through the disappointment of failing to bring home gold at the Rio Olympics by keeping a gratitude diary. I wrote in it every day. Our mental skills coach, David Galbraith, would ask, ‘What did you do today that made you proudest?’ and ‘What would you do better if you did it tomorrow?'”

Ruby is an outgoing “people” person. She finds it easy to make friends and that stems from her childhood. She was born in Wellington in December 1991, to Marion Mouat and Kovati Tui. Her heritage is Irish/Scottish on her mother’s side and Samoan on her father’s. She’s often mistaken for having Maori tribal affiliations – she laughs about a Wikipedia entry that details Ngai Tahu links.

“Careful what you believe from Wikipedia,” she warns.

Kovati is a builder, her mum, Marion, now works as an interviewer for Statistics New Zealand. Kovati and Marion had a troubled relationship. “They argued all the time,” Ruby remembers. Her dad has since been open about his alcoholism.

As Ruby tells it, “One day Dad said to me, ‘Bud, do you want us to get married, cos if you do, we can do that.” She fixes me with her brown eyes. “True happiness is much more important than that ‘picture’ of happiness… they were definitely happier apart. I was not embarrassed about having parents who separated.”

Ruby was aged about eight at this time. She left Wellington to live with her mother and her new partner in Takaka, near Nelson.

It was not a happy time.

“Mum was working all hours trying to establish a new business. I don’t know how she did it.”

In 2000 her brother Dane was born. It was not a good year. She adored her younger brother but her mother’s relationship was falling apart.

“Sometimes as a kid you can just tell things are not going to work, but you have to let them work it through.”

The family was struggling to make ends meet and put food on the table.

“I think this made me a lot closer to Mum,” Ruby says. “I have a lot of respect for her, washing dishes, waitressing. I think Mum taught me that you can always get a job.”

Sometime later, in an effort to take a bit of the load off her mother, Ruby made the choice to return to Wellington to be with her father.

“Dad gave me a lot more freedom when I was with him. I thought, ‘Man, I’m cool.'” But it wasn’t long before she decided that life wasn’t for her. “I saw things at a young age that made me say straightaway, ‘I’m never doing that, I’m never going to waste my life away.'”

It might have been easy for Ruby to go off the rails, but she credits her dad for keeping her strong.

“Dad has a good heart and lots of love for me. He would whisper in my ear all the time, ‘Bud, you’re the best.’ I think it bloody stuck!” she laughs.

Ruby was enrolled at Wellington East Girls College and then suddenly found herself back with her mother, this time in Greymouth on the West Coast. “I made Mum promise there would be no more moves.”

She’d been to six schools by the time she arrived at Greymouth’s John Paul II College, and was well over moving. It had been hard to maintain friendships – each time she moved she’d have to start again. It was tough, but it was sport that pulled Ruby through; it was a way to make instant friends.

“I played everything. Netball, soccer, rugby, squash.” Netball, though, was her great love. “I’d spend all day at the courts, reffing, jumping into other games.”

John Paul was a small school and Ruby represented it at pretty much every sport it offered. At home, though, things were not going well and eventually the family ended up at the Women’s Refuge in Westport.

Ruby remains enormously grateful to the Refuge and is keen to support their work in any way possible.

“They are amazing, they helped us so much.”

She also credits members of her extended family for supporting her through the tough times. Her father’s sister Tala was another mother figure, a constant in her life. “I spent half my childhood with Tala. I adored my cousins. No matter what was going on, I found lots of treats and love with Tala.

“Mum’s brother, Uncle Neil, was a father figure. He ran a horse farm and cottages on family land at Punakaiki. He built the cottages himself, he showed me what hard work can do. His place was an escape for me. He once spent $300 on a pair of netball shoes for me. I couldn’t believe it. It was nothing much to him but, to me, it was everything. I always think of these people as two pillars in my life.”

It wasn’t until she enrolled in Canterbury University’s Media and Communications degree that she discovered the joys of women’s rugby.

The student accommodation was right next door to the rugby fields. The accommodation was expensive. When she was asked to come up with the quarterly rental, she realised the lump sum her mum had put down at the beginning of term was only enough for a couple of months’ stay. Ruby had to find a job, fast.

As luck would have it an aunt found her work in the university bar. With that, and jobs she found online, she managed to scrape together enough to pay most of her board. Every couple of months she would gather every cent she had and take it to the office.

“This is all I have,” she’d tell them.

They obviously saw the promise in the young girl from the Coast, and let her stay, even though the money barely covered their costs.

Ruby began playing rugby because she didn’t have to pay for the bus to get to practice. She found she was a natural. She relished the fact that although there’s supposed to be no contact in netball, rugby was all about contact and she wasn’t confined to one part of the field. She could run free, she was in her element. She was playing with the elite of the sport in her university club team.

At that stage Casey Robertson was one of the world’s best.

“She was powerful, off the farm, she’d just brush Black Ferns off in tackles. I loved to watch her. Then one day I tackled her and she came down and I thought, ‘Holy heck – I just tackled Casey Robertson!’ It was a light bulb moment. I thought, ‘I can do this.'”

This was 15-aside rugby; Ruby was small for the sport, but quick and strong. Then, in the summer of 2011, she discovered Sevens.

“Suddenly, being smaller and quicker became an advantage, it was a whole new world. I wasn’t any good at passing. I never lacked heart, mongrel and fight, but my skills needed work. I thought I’ll do anything to get better at this game. I went to every single training. They were all reps in the team but many of them had other calls on their time. I just kept turning up and eventually they must have thought. ‘This young, eager chick just keeps turning up, we’ll put her in the team,'” she says.

The first tournament was in Australia. It went well. And here we come full circle because it was Mere Baker who was coaching that team. She was fierce. She took no prisoners.

Ruby remembers it vividly.

“We were running. There were the good girls, the mid group, the stragglers, then there was me. Mere was watching me, I was intimidated by her. She said, ‘You know you can go faster, eh? If you catch that group, I’ll make you the best sevens player in the world.’

“With that I just started running faster, I passed the stragglers, I had a mental breakthrough. My whole body changed, I could feel the physiological effect on it.”

For the past seven years Ruby has held on to that mind-body connection.

“Unlike most women, I’m constantly trying to put weight on. I have to eat every two or three hours or I swear I can hear my muscles eating themselves.”

She’s careful what she eats – 20g of protein, carbs then micronutrients like iron and amino acids. “Mentality has a huge part to play [in staying match fit]. If you’re struggling, worried or stressed, you will get injured – that’s my experience.”

Sevens rugby brings its own peculiar stresses. With 15-aside, it’s all over after 80 minutes; in Sevens it’s 48 hours of constant readiness.

She runs through the post-match routine for me. First, hand sanitiser. (“Germs cost medals,” she tells me sagely. She was the player sidelined by the mumps at the last Commonwealth Games.)

After the sanitiser, it’s lollies to replace the sugar lost, then a team-talk, food, ice baths and a shower.

“For me, the shower is a metaphor for dropping off the last game, then I like to nap until the video replay – it can be five minutes or two hours, it doesn’t matter. Lastly, we wake up the body with exercises on rollers. We listen to Stan Walker sing Aotearoa before we head onto the field to warm up, the captain talks, then we’re into the next game.”

The Black Ferns do have a unique culture.

“The girls who started with me in the World Cup Sevens squad in 2012 will be friends for life. We are all so different, but we all bring something different to the team. We’re always laughing and having fun.”

She says Maori culture has a huge impact on the team’s success. The coach and several players are fluent in Te Reo. Team talks are all in Te Reo, then translated. Many of the on-field calls are in Maori.

“The language contains so much wisdom that is not literally translatable; words can mean different things to different people, but we all buy into it, it’s genius!”

They save their powerful haka for the end of the tournament, if they win.

“It’s all about respect and honour.”

That haka – in all its pride, glory and sheer joy – has become synonymous with the team.

Ruby is relishing her time in the Sevens team; this is her seventh year.

“I still can’t believe I get two pairs of boots for free,” she says incredulously.

She loves the game so much she’s had two goal posts intersected by a heartbeat tattooed on her ribs. These days she combines her love of rugby with her communication skills as a commentator for Sky TV.

“I love the ability to connect with an audience. Sky has helped me grow as a person. I hope I can make my family proud.”

She lives close to the Sevens training headquarters in Tauranga with Taryn, her partner of five years. She doesn’t necessarily identify as gay.

“It’s all about love. I’ve had boyfriends before. You need someone to care about you. Taryn has supported me as a person and she supports my dreams.

“I have created standards for myself that I hold dear. Mental health is important. You have to learn to figure yourself out and prioritise that. I hope that people figure that out, focus on themselves and understand who they are, then they can make the world a better place.”

As for her beloved Sevens?

“I hope we go down in history as one of the most successful sporting teams in the world.”