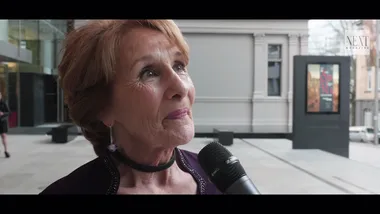

Category winner for Arts & Culture: Carla van Zon

In June last year, Carla van Zon collapsed on the floor of a Western Union money-transfer branch in Montreal, during a trip scouting shows for the 2017 Auckland Arts Festival (AAF). She’d put the extreme tiredness down to a busy schedule and a lingering flu, put the swollen feet down to all the flying, and put the metallic taste down to something she’d eaten.

After collapsing, she was diagnosed in a Montreal hospital with chronic kidney disease (also called end-stage renal disease). Knowing little about it, she asked what she needed to do. The answer was life-long dialysis, unless she could get a kidney transplant. In dialysis, the cleansing fluid dialysate flows through a tube into your abdomen to filter waste products from your blood. Average life expectancy on dialysis is five-10 years.

“Yes, I was scared.”

Back home, she found neither sister was a match for a kidney transplant, but a close friend was. A year later, her friend is – frustratingly – still awaiting final tests to determine if the operation can go ahead. It’s unlikely she’ll get a kidney from a deceased donor, as the 700-name waiting list is ranked by how long you’ve waited, and many of them share her blood type O. She’s angry about New Zealand’s under-funded, over-stretched, inefficient health system, but her iron will and laser-like focus is intact. “I’m determined to get the transplant and get to a friend’s 70th in Italy next year.”

The 65-year-old did everything possible – including drastically changing her diet – to stay off dialysis, because she hates being hooked up to a machine for 20-30 minutes every four hours, and because life expect-ancy is best if you go from diagnosis to transplant, skipping dialysis.

“But the doctor told me in August I’d be dead by Christmas without peritoneal dialysis, so I’m doing it myself at home.”

She began dialysis after hosting her fourth and final AAF in March as artistic director. She had planned to retire at 65 anyway, but the plan was to enjoy Totaranui Orchard – her lifestyle block near Otaki – and travel for pleasure rather than work. Carla spent six years catching flights from Kapiti Coast Airport to Auckland to work four days from the AAF office, staying three nights with friends. Her regular overseas trips to scout talent weren’t glamorous. In Europe, it was usually a country a day with many hours in transit, and no time for sightseeing.

Used to working flat-tack, she’s finding it hard to adjust to doing little. Between the dialysis and debilitating tiredness, she can no longer manage her vege garden at Totaranui, but is walking on the beach a lot.

When NEXT visits she’s finalising the latest arts event she’s producing in an Otaki community hub. Outside, her husband Gregg Fletcher is making cider from their apples. She brought him back from Washington, D.C. 35 years ago along with her Master of Arts; they decided against children.

Ten years later, they moved to central Wellington when Carla joined the New Zealand International Arts Festival (now the NZ Festival). During 12 years there – half as executive director, half as artistic director – she brought the festival out of the red, and it won local economy and national tourism awards. Later, in Auckland, she oversaw the AAF’s transition from a biennial to an annual event, and doubled attendance numbers, including drawing a younger demographic.

At both festivals, she increased box-office income; introduced greater divers-ity including work by women and Maˉori, Pasifika and Asian artists; and convinced many globally influential artists like Canadian playwright Robert Lepage to bring their work down under. The international and edgier shows have influenced many local artists.

She’s proudest of commissioning and presenting New Zealand work. “We need to tell our own stories.”

The numerous arts practitioners she’s championed and commissioned include playwright Hone Kouka, visual artist Lisa Reihana, composer Gareth Farr, and playwright Renee Liang (who wrote an opera for the 2017 AAF).

Carla’s ongoing legacy project Whaˉnui saw the 2017 AAF co-produce five participatory arts projects where local artists worked with community groups, including the marae-led creation of a korowai (cloak) that incorporates 7500 tiny perspex houses. She’s also led artist-development initiatives including the AAF’s RAW, where artists present a work-in-progress to an audience.

During her stints at Creative New Zealand, and the NZ Arts Council, she oversaw the development of successful strategies to help New Zealand arts practitioners achieve international success, including touring Asia.

Her legacy includes NZ at Edinburgh, where New Zealand arts practitioners participate in the various Edinburgh festivals. Fondly dubbed Aunty Carla, she’s also mentored many arts-industry colleagues, including WOMAD programme director Emere Wano and CubaDupa artistic director Drew James.

One of her biggest contributions has been demystifying art, “switching on” people to art forms they never imagined they’d enjoy. She sees art as a communion between artist and audience, something that creates a sense of community. “You’re seeing work that reflects your life, or helps you understand other people – and that they’re not so different to you.”

Judges comments

“Festival director, mentor, talent scout, commissioner of the arts… Carla has poured her energy, heart and soul into bringing art to ordinary Kiwis and we are all the richer for it. She is nothing short of inspirational.”

Category winner for Business & innovation: Ranjna Patel

If you build it, they will come. Raised in a Herne Bay fruit shop – back when the upmarket Auckland suburb was a different world entirely – there was never a career plan for Ranjna Patel. One of seven kids, it was her three younger brothers who had the big hopes pinned on them.

And yet it is Ranjna who is the co-founder and director of Nirvana Health Group, New Zealand’s largest independent primary healthcare group. When she and her husband, Dr Kantilal Patel, opened East Tamaki Healthcare in South Auckland’s Otara in 1977, it was the time when the lower socio-economic suburb was experiencing the infamous machete murders and dawn raids.

Kantilal had already faced challenges: even though he was a fully trained doctor in India, he had a long battle to get registered so he could work here. But after doing so, and trying to move into specialised medicine, he was told by one specialist that central Auckland was not ready for a coloured specialist with an accent, so they should move to an area that ‘looks and sounds like you’.

Otara was the answer: a working-class area that was being let down by its local services.

“People couldn’t take an hour off work to come to the doctor, because they’d lose their job,” Ranjna, 62, says. The couple immediately opened their doors from 8am-6pm, instead of the standard nine to five. They also charged as little as they could to keep their fees achievable for the locals.

“Basic 101 business: if you meet your customers’ demand, your business will grow.”

And grow it did; they had to move premises regularly to make room for their expanding client base. Ranjna took on many roles: receptionist, cleaner, book keeper, accountant.

“Being brought up in a fruit shop, we all learned the value of customer service,” she says.

Forty years on, East Tamaki Healthcare is now Nirvana Health Group, with 35 clinics across three cities, 4000 clients a day and 1.2 million visits a year. They’ve also invested in a Sydney-based healthcare business.

Even after a business acquisition, where they had the possibility of moving their office to Auckland’s CBD, Ranjna stood fast: they began in Otara, they were staying in Otara. “That’s our roots,” she says. The population in South Auckland has grown hugely in the past 40 years, and the issues their customers face are part of a bigger problem.

“Health is part of it, but it’s also lack of good housing, food, education,” Ranjna says. “If you could deal with those issues, you could deal much better with the health.”

For her it’s paramount that Nirvana staff have the right ideals. She sits in on every final interview to ask potential candidates: “Are you here to serve the community?”

This is what is behind all the work Ranjna does; she and Kantilal also built a Hindu temple in Papatoetoe for the Indian community, where they feed 500 people every Sunday. Ranjna jokes she can’t attend a service without being handed a CV, or a document to sign (she’s a JP), or being asked wedding questions (she’s also a marriage celebrant). But there’s a darker side of community life she’s also been helping to combat.

The police asked her to join their South Asian Advisory Board after a disturbing statistic about family violence came to their attention: in 2012/2013, four out of 14 women killed were Indian.

That figure was disproportionate with the Indian population, and the police wanted help. Ranjna went to Manukau Institute of Technology to do a social work course, and gathered together Family Violence officers and the relevant NGOs to discuss a plan.

“I didn’t believe it was an Indian problem. I believe it’s a community problem. You can remove the woman, but then the man just goes onto another woman and hurts her. I knew we needed to help the men to then help everyone.”

She got nine providers together, eight of whom dropped out once it was clear funding would be an issue. But one stayed on, and with the help of counselling charity Sahaayta, they created Gandhi Nivas, a home for men who needed immediate counselling to tackle domestic abuse.

Gandhi means ‘man of peace’, Nivas ‘home’. With in-house social workers, it’s a place to stay, cool off and get help – as opposed to a trip to jail, where the men end up with a criminal record, a factor which can put their wives off seeking help in the first place. It’s for early intervention, Ranjna says, rather than serial offending; they have a three strikes policy.

“You have to want to change,” she says. “It’s not a hotel.”

But Gandhi Nivas is working. Out of the 640 families they’ve dealt with since the home opened in 2014, only half a dozen have said it was an ongoing problem. An overwhelming majority of the men have never reoffended; and the biggest victory, Ranjna says, is the fact men ring and ask for a place to stay because they can sense their stress triggers coming.

While it was initially for South Asian men only, Gandhi Nivas now caters to all ethnicities. “It works across all cultures and all socio-economic areas,” she says. “It’s not just a poor man’s disease.”

Her aim is to change the intergenerational effect of abuse: “So the children don’t grow up thinking ‘Dad hit a little bit, it’s okay.'”

Her dream is to take the model nation-wide; West Auckland will soon get its own peace home, then Waikato, then Lower Hutt. Spare time is rare; Ranjna is also on numerous boards, well aware of the power she has but also the minorities she represents.

She often wears a traditional sari when presenting at business conferences, wanting to make the audience aware of the unconscious bias people like her and Kantilal have had to work with their whole lives.

“I feel as a rule, women don’t get asked to do things or speak at things. Ethnic women even less. Now that I get asked to speak, I’m too afraid to say no. I’m in a privileged position, with the amount of people walking through our doors, and the difference I can make.”

Judges comments

“Ranjna is outstanding in her category – not solely due to her business’s huge success, but because of her unwavering focus on serving her community and being a role model to the minorities she represents.”

Category winner for Health & Science: Melanie Cheung

The word Melanie Cheung uses to describe herself the most is “lucky”. A better word to use, however, would be ‘ballsy’. This is a woman who, when she couldn’t find what she needed to help heal people’s brains, told her supervisor “I might just have toinvent a new type of science.”

At 41, Melanie is not only one of a handful of neurobiologists leading the world in fighting degenerative brain diseases, she’s also busting stereotypes left, right and centre about what we think of when we think of a scientist. She is not a white man with a beard and glasses.

She is a cool, half Tahitian-Chinese, half Maˉori woman with a signature shade of lipstick (MAC Lady Danger) and shiny silver brogues. And she is fighting long and hard against one of the cruellest diseases on the planet: Huntington’s.

The disorder is described as being motor neurone disease combined with Parkinson’s combined with Alzheimer’s. A degenerative illness with a cruel twist: if you have it, your children have a 50% chance of getting it. At one conference Melanie attended, she heard from a woman who had nursed her mother-in-law, her husband, one of her children and was now staring down the barrel of nursing one of her grandchildren.

With all degenerative conditions, it is the lack of hope that can be the hardest to bear, for the sufferers and for those around them. And in New Zealand, we have an especially high incidence of Huntington’s, with Maori most heavily impacted. But there is a glimmer of light, growing by the year, thanks to Melanie’s work at the Centre for Brain Research, University of Auckland.

It was after completing her PhD, where she grew human brain cells from cadavers and tested treatments on them, that Melanie was at a loss of what to do next. She knew she didn’t want to make drugs, she wanted to help fix people whose brains were deteriorating.

“I knew there were already behavioural therapies, but those therapies don’t slow the Huntington’s brain from dying. But neither do any drugs. I knew there had to be another way.”

By chance, a friend gave her a book called The Brain That Changes Itself. “It was the science of people who were pioneers before their time – helping deaf people hear, helping blind people see.”

One chapter featured the work of Dr Mike Merzenich, a neuroscientist based in San Francisco who was using neuro-plasticity-based cognitive training – ‘brain training’ – to help treat stroke, dementia, multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia and learning disabilities. Neuroplasticity is how your brain changes and adapts itself; most of this happens when we’re younger as we’re being exposed to new experiences and our brain needs to adapt to them.

Melanie tracked him down and sent him an email, introducing herself and her hypothesis that brain-training could also work for those with Huntington’s.

“I had absolutely nothing to lose. I said: ‘Do you want to work with me because I’m young and I’m hard-working and I’m bright?'”

Dr Merzenich emailed back the next day, and so began the professional partnership that would see the pair create the ‘FightHD’ neuroplasticity-based training programme designed with the aim of slowing down the cognitive impairments that come with Huntington’s.

The general theory, Melanie explains, is that the brain changes caused by the disease happen long before the motor function deterioration, so if the brain training can slow the cognitive changes, then hopefully it can also slow the physical and emotional changes. Basically, if successful, the programme could buy precious time for those facing a disease that progressively kills off body function after body function (concentration, thinking, planning, decision-making, personality, emotions, movement, balance, coordination, speech production).

There are 98 people currently enrolled in the HRC-funded FightHD programme. It’s time-consuming; 100 hours of brain-training: half an hour a day, five days a week, for 40 weeks.

There are 28 volunteers who’ve finished their training so far and the results are looking good – so good, in fact, that the MRI specialist re-did the MRI analyses 40 times, just to be sure the data was real.

They won’t know until a couple of years down the track how long-lasting those changes are, but in the meantime, “We’ve got a lot of very happy research participants who feel like it’s changed their lives. On a science level it’s good, but at a human level, we’ve got these amazing, resilient communities who finally feel hope again,” Melanie says.

The pace of this project is huge; for the next generation of Huntington’s – and there is always a next generation in this inherited disease – it is a race against time. Melanie and her team – she lists about 25 people who are instrumental to the work – have been working around the clock for years to get this done.

Next to her desk, Melanie used to keep a photo of a young woman she had worked with, right back at the start of her PhD. She had attended this girl’s 21st birthday, which her sick father had tried to hold on for. He died nine months before his daughter’s birthday, and the memory is still raw for Melanie.

“When it was 12- or 16-hour days – and it’s still like that now – and I’d think ‘I can’t do this any more, it’s too hard,’ I’d look at this girl’s photo and think ‘these are the people I’m going to keep working hard for.’ The communities we work with are what keep us going. They’re the reason we get to do the work that we do.”

Judges comments

“Here is a woman making huge strides in finding a treatment that has eluded scientists for years. Melanie is the embodiment of what can be achieved when a brilliant mind is coupled with a big heart.”

Category winner for Sport: Heather Te Au-Skipworth

Creating Iron Maori, the world’s only indigenous half IronMan, is quite the triumph, but Heather Te Au-Skipworth’s career has been built on big challenges.

When she started as a health coach, her first client threw down the gauntlet on day one. He said, “My doctor has referred me to you; I have to lose weight or I’m going to die.”

As Heather puts it: “I didn’t know how I was going to help him not die, but I knew that I could build a relationship with him, and earn his trust.”

With her help, that client went from 180kg to 84kg. Heather built a loyal following in her hometown of Pakipaki, near Hastings, giving people the tools they needed to get their weight under control. She created a gym that was less scary Lycra and more of a safe space where bigger clients could feel comfortable and motivated, that they were among friends.

It was this initial experience that paved the way for her to eventually create IronMaˉori, an event which took that safe space and made it a country-wide movement.

Making sport both financially accessible and comfortable for her clients was the point of difference for Heather right from the start of her career. After dropping out of high school because she found it “a bit boring”, she did a certificate in exercise and nutrition at the same time as becoming an aerobics instructor.

She took the fitness trend of the time – Tae Bo – and learned it herself so she could run her own classes, where she charged people $5 a pop rather than the normal $20. It was during this time she was shoulder tapped to become a gym manager and a lifestyle coach.

But after working with her clients, she realised she wanted a bigger goal for them, to bring about bigger change. It was after she completed a few triathlons – “I felt like it was going to half kill me” – and moved onto training for her first IronMan that Heather got an inkling of what it must be like for her clients.

The full IronMan is widely believed to be one of the most difficult sporting events in the world; you swim for 3.8km, you bike ride for 180km, then you run a full marathon: 42km.

About three months before the event, Heather had signed up for a half IronMan to see how she was going in her training. She completed it in just under the allotted amount of time – “it was a big, Sir Edmund Hillary achievement for me” – but when she rang her trainer to tell him, he told her maybe the IronMan wasn’t for her; that she should rethink it.

“It made me think of my clients – how many times in their lives people have said that to them. That really drove me to keep going; I wanted to prove that I was right.”

So she did the full IronMan, and completed it well under the allotted 17 hours. All 30 of her clients came out to cheer her on as she crossed the finish line. The sense of achievement, Heather says, was indescribable.

“I thought, ‘If I could transfer what I felt on that day for my clients, the world would be their oyster.'”

Her goal was born: “I wanted to create an event that was so physically challenging, it would force a lifestyle change.” But she wanted to do it within the safe space she’d created for her clients, and to cater for the Maˉori and Pacific Island community.

“When we went to mainstream events, everyone was very well-maintained. With my clients, the average weight would have been 100-150kg. They felt self-conscious. I wanted something where it didn’t matter what size, shape or form you are.”

And so Iron Maori was born; a half IronMan event for those who would not usually consider tackling such a goal, and the name courtesy of her husband Wayne.

The first event was held in 2009 with 300 people. The next year, 600 applied. The third year, 1550. The fourth year, more than 2000 signed up to do the 2km swim, 90km bike ride and 21.1 km run. There are now eight events under the IronMaori umbrella, including kids’ events, seniors’ events, women’s only events; more than 50,000 people have taken part.

Heather jokes it’s “the world’s biggest Maˉori Lycra party”, and there are now events around New Zealand and Australia.

“Eventually we want to take it to other indigenous countries, to smaller communities there and show them how to do it, and then step away so it becomes theirs. We’d love to attract more international people to our events as well; we are the only indigenous multi-sport organisers in the world.”

On a personal level, Heather says it’s made her far more confident; she used to cry during public speaking, now she jokes you have to yank the microphone away from her. “I’ve always got this big drive to learn more. I’ll set challenges and achieve them, but it’s not enough. I’m always asking: what’s next?”

Judges comments

“When it comes to empathy, Heather truly goes the distance. By relating to the needs of those who don’t fit the traditional ‘sporty’ mould, yet also setting the bar high, she’s empowered thousands of Kiwis, helping them achieve fitness goals beyond their wildest dreams.”

Category winner for education: Dame Wendy Pye

The No 1 question not to ask Dame Wendy Pye is: When are you going to retire? At parties with fellow 70-year-olds – “the worst kind of parties” – it’s what she gets asked the most. You can understand the question – Wendy is 74, and also reportedly worth more than $100 million. But the retired life doesn’t appeal to the founder and publisher of Sunshine Books.

“You have two choices: You either do something like sail around the world – I can’t think of anything more boring – or you put that money back into something.”

At the time of her NEXT interview, Wendy is recovering from the flu, but apart from a nasty cough, you wouldn’t know it. Resplendent in a hot pink blazer and a string of pearls, she looks like a lady and she talks like a gangster. She likes fast cars, good jewels, and racing horses because she enjoys “beating the boys”.

Wendy’s two life philosophies are: what you put into life, you get out of it; and to treat people the way they want to be treated.

“There are people who are ruthless, but that’s a pretty lonely life. I’ve had to make hard decisions, but I haven’t made enemies along the way.”

Her Sunshine Books office in Auckland, she jokes, is like “the Sunshine retirement village”, on account of the fact everyone working there (minus the young ones doing technology) have been there at least 20 years. Her art director has been with her 44 years; her secretary for 42.

The origins of Sunshine Books are the stuff of legend; surely somewhere a screen-writer is working on turning ‘the Wendy Pye story’ into a movie. Back when she was in journalism, she saw three 13-year-old Pacific Island boys who couldn’t read, and she was appalled. “It was the most disgusting thing I’d ever seen. They had no self-esteem; how could they possibly take their place in the world?”

It created her core belief and the ideal that would shape her Sunshine Books empire: literacy is the way out of poverty. She wanted to stop kids from falling through the cracks and she knew education would be their ticket to a better life. So she called together authors and educators, found out what works for every child and created her own line of books.

She took them on the road in New Zealand, then exported to Australia. Then she went to Europe. Then to the US, to China, to South Africa, to Asia. Sunshine Books has sold more than 300 million copies worldwide, and has launched numerous digital platforms globally.

So what does Wendy do next? Well, she has one big, audacious goal she’s aiming for in the next five years. There are 59 million kids who don’t go to school – “mostly girls” – and 124 million people without access to literature. The solution? The Sunshine Super Reader: a solar-powered digital tablet pre-loaded with hundreds of e-books and 1000 activities – a one-stop shop that will teach them how to read.

It’s already in Asia, and soon will be rolled out in Africa, India, and the more isolated parts of South America. She wants to get it into the hands of refugee children around the world, currently out of school.

“If I can educate those kids, they’ll get a job and they won’t be isolated. People who aren’t part of society are the ones at risk.”

But Wendy hasn’t left books behind. Next year she’ll roll out a nationwide launch of reading material across China. When she showed the Chinese embassy in New Zealand what she had in mind, they told her it was amazing. Her reply: “You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Her next key project? To upgrade Maori education: “How do we make them feel good about themselves? Forget about the Ministry of Education. We just do it.”

There’s a plan to get books into Spain – “good wine!”; to Russia – “I love the emeralds!” That’s why there’s no retirement on the cards yet, when there’s so much world domination left to achieve.

“We’re changing people’s lives. We’re getting on with it. What would I do if I retired? I already make jams and pickles,” Wendy says.

“I’ve worked with three generations of children: I’ve seen them learn to read, get a job, feel good about themselves. If we’re lucky enough to be given the skills or ability to make a difference, I think it’s our responsibility. Don’t you agree?”

Judges comments

“Dame Wendy’s publishing empire is a Kiwi institution to make us all proud. She could be relaxing in style; instead she’s living out her ‘retirement’ as she has lived her whole life: changing lives one book at a time.”

Lifetime achievement award: Theresa Gattung

This is our eighth NEXT Woman of the Year, and we’re marking the occasion with a Lifetime Achievement award for a Kiwi woman who exemplifies the traits we look for: successful, community-focused, intent on making the world a better place. We’re delighted to name Theresa Gattung our 2017 recipient. Here she outlines what she believes we need to focus on.

Next year marks 125 years since women in New Zealand won the right to vote. After Kate Sheppard and her colleagues secured votes for women in 1893 following a 14-year campaign, they identified their next highest priorities as: pushing to allow women to become MPs, which took a further 25 years; the economic independence of married women; the right for divorced women to retain custody of their children, and equal pay for work of equal value – 125 years later we’re still waiting for the latter.

I recently read Manal al-Sharif’s book, Daring to Drive. She was ultimately forced to leave Saudi Arabia and lost touch with her eldest child for daring to drive.

One of the most disturbing parts of the book was how much hostility she invoked from other women when she sat behind the wheel of a car that day. In that society the limits of female autonomy are low. In our society they’re higher, but we don’t value women having any equal place in public life or we wouldn’t accept the absence of women taking an equal seat at the table in business, in large business in particular.

It’s still gob-smacking that in 2017 we have only one female CEO of a top NZX listed company.

How can this be? Because as a society a picture of a leader still looks like a tall white man. In Chimamanda Adichie’s wonderful book We Should All Be Feminists she says if we see the same thing over and over

again it becomes normal. As Aunt Lydia helpfully outlined for us in episode one of The Handmaid’s Tale, once you see the same thing over and over again you become used to it and you forget the way things were before.

If we keep only seeing men as heads of companies and as leaders, it starts to seem natural that only men should be heads of companies. As Chimamanda pointed out, the person more qualified to lead is

the more intelligent, the more knowledge-able, the more creative, the more innovative.

There are no hormones for these attributes. A woman is as likely to be as intelligent, innovative and creative as a man. Women are still too invested in being liked; we don’t teach boys to care about being likeable.

But just as in Saudi Arabia, women are half the population. Ultimately it’s us also saying “this is good enough”, that the place women hold in our society is enough. Gains made can be lost if they are not claimed and reclaimed. We should never take what we have achieved for granted. It’s still harder to be a woman in public life than a man. And it’s important we don’t judge other women and their choices.

Women are paid less than men in every country in the world. It is like this in New Zealand because we all accept it. Ultimately we’re all part of the system and we need to take concerted action. In 2017 it is totally unacceptable that equal work of equal value is not paid for equally. New Zealand is a country that values treating everyone equally.

It matters to us, let’s fix it.