Sparks cascade from the whirring bench grinder as Joy Cowley skillfully twists the blades of her metal tools across the spinning stone face, her fingers millimeters from razor-sharp edges. Inside the double garage at the back of her Featherston house, the 82-year-old children’s author, and newest recipient of the Order of New Zealand, is equally at home with her power tools as she is tapping away on a computer keyboard.

It’s in this workroom, with neatly stacked wood rounds to one side and tables upon which her prized skill saw, grinder and lathe sit, that the Kiwi woman who has made a literary mark internationally is pursuing her wood passion.

It’s a hobby that dates back some 70 years, when she donned overalls and helped her father build the family home in the Horowhenua township of Foxton.

With cuts perfect for moulding into bowls, platters and even pens, Joy is in her element, working the raw material on her lathe.

“I quite like doing bowls with paua shells and resin on the inside,” she tells.

Placing a chunk of sequoia on the machine, she begins to methodically and meticulously run her gouge across the face of the spinning wood, revealing a smooth, round surface with contrasting shades of red. A bowl quickly takes shape before our eyes.

“I’ve always liked working with wood since I was a child,” says Joy. “I used to make doll houses and rocking horses.”

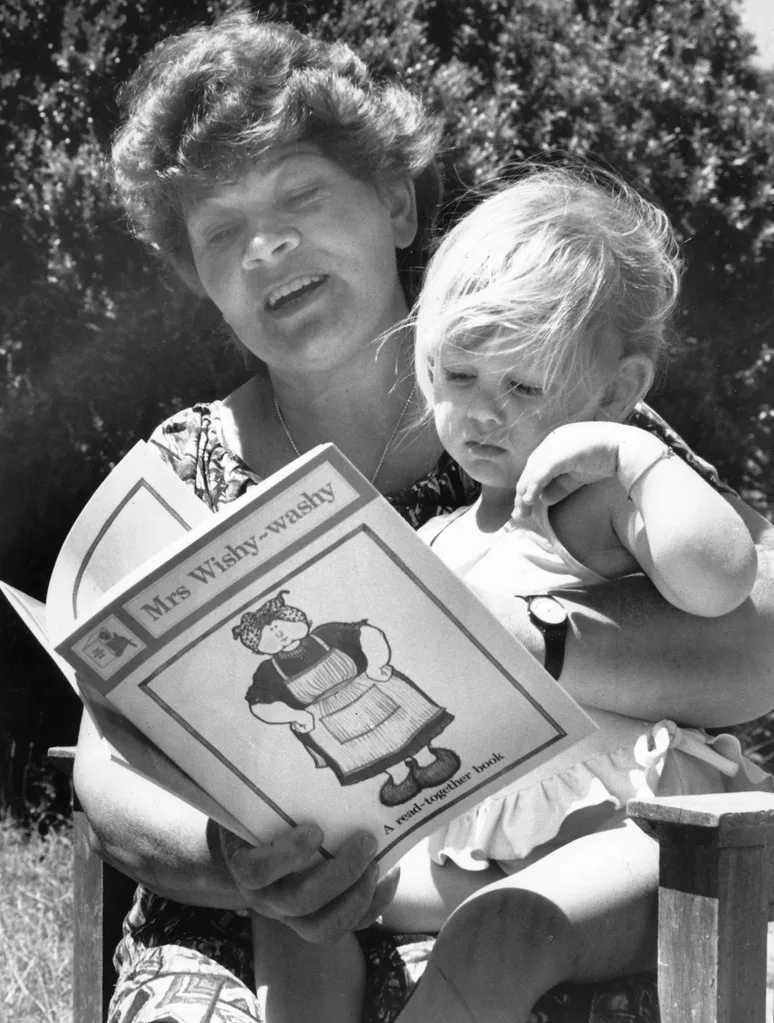

Within 15 minutes the lump has a base and curves and Joy, a study in concentration, is covered in wood shavings. It’s a hobby that’s held the fascination of the woman behind Mrs Wishy Washy for the past 20 years when she took up woodturning and piano at age 60 because, for the first time in decades, she had time to do it.

“I’ve always messed around with wood. When we bought this cottage, it had this big shed out there and I knew I was old and wouldn’t have too long to learn woodturning on my own so I did two courses,” she tells, adding that she proudly lists her Aoraki Polytechnic diploma on official documents. And while the piano playing has taken a back seat − “I stopped at grade six because my fingers wouldn’t go fast enough but I did get satisfaction from learning Debussy and Chopin and I now play these very slowly” − the love affair with wood continues, with the author disappearing for hours at a time into her workshop.

It’s something to which she will be devoting more time than ever with life switching gears earlier this year after her husband Terry Coles suffered a serious stroke. The couple decided to permanently relocate to Featherston soon after.

“We did have an apartment in Wellington and we sold it because Terry couldn’t cope with the stairs. That was a sensible thing to do,” says Joy. “I used to go out a lot doing talks, but I’ve cut right back this year. I can still go away for a couple of days and do other things, but family [need to] move in with him.

“He’s 88 and he’s managed very well to come out of this because we wondered if he would − he had three weeks in hospital in February. He had two minor strokes before where he lost the left hemisphere of vision and left hemisphere of hearing, but this one was by far the worst.”

Nowadays you’ll find the pair pottering around home, their garden full of winter greens and citrus fruit, with Joy still rising at 4am to write.

As she sits down to a morning tea of freshly baked gingerbread loaf, the celebrated author reveals her incredible shock at discovering she was in line for the distinguished honour.

“You know when something is so surprising you go into brain freeze? Well, that’s how I was,” she tells. “I stared at this letter and the words Order of New Zealand didn’t have any meaning in the context of me.”

Even thinking there had been a mistake, Joy confesses it took time to recognise herself as a worthy recipient but values the medal’s special provenance, saying it seems “so right” and very meaningful.

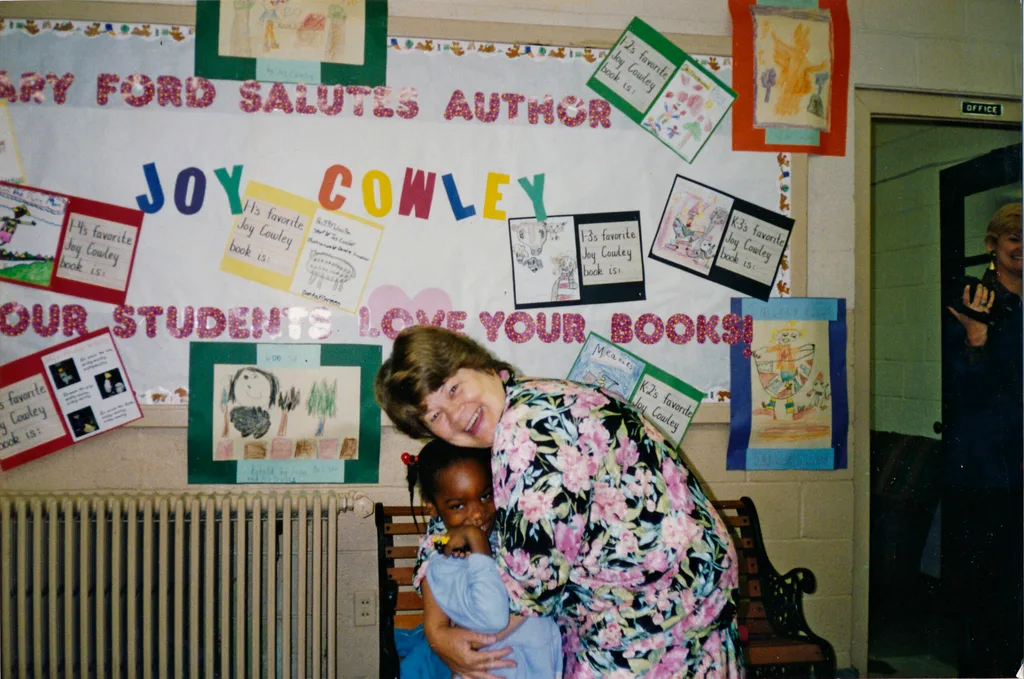

“I thought it was a lovely order before I got it because it doesn’t have a title and because I work with children I don’t use titles − they just know me as Joy or Joy Cowley − and I wouldn’t want anything to get in the way of that.

“But also each medal is a heritage thing. It gets passed from person to person and obviously they think about that stream of inheritance because when I die it’ll probably go to someone else who is either in education or the arts.”

Her medal’s predecessor, artist Cliff Whiting, had previously worked with Joy illustrating a school journal story and a book. Before that, the medal was worn by Clarence Beeby, credited as the architect of our education system.

Joy, who started writing for adult audiences, tells the Weekly her switch to children’s books was initially to help her son Edward, who was struggling to read.

“I had the same problem but for different reasons when I was at school and I know how failure felt, classifying myself as a bad reader,” confesses Joy.

A teacher encouraged the talented mum to write stories for him that combined meaning with a word list for beginner readers.

“I found that children related best to stories about themselves, so I started making personal books for children who struggled with reading.

“Edward and another boy couldn’t relate to fiction, so they really wanted stories about their interests. They would tell me about volcanoes and dinosaurs and it would be their interpretation I would put down in their stories,” she says.

“Edward is 60 this year and he still reads for information – he doesn’t read fiction. He still picks up a copy of the old Encyclopedia Britannica and starts reading it!”

Joy was writing for school journals and early readers when her much-loved Greedy Cat series was born. She says she still has no trouble recounting works that are very popular with the children, but there are others she’d like to disappear.

When it comes to the inspiration for her work, it’s a simple formula.

“It’s part memory, part senses,” explains Joy. “There’ll be a sensory trigger − something happens that I can see or hear or smell that reminds me of when I was a child or told to me − but once you get one idea, others will cluster around it. It almost seems to be magnetic.’

“When I lived in Khandallah there was a school down the end of the street and children, with their parent’s permission, used to come in and have hot chocolate and cookies, and they would talk to me mainly about their pets and what they did. One little girl was very excited because they had a new kitten and I said, ‘What’s it called?’ and she said, ‘Oh. it’s got a real name but I can’t remember it because we call it Greedy Cat because it’s greedy’. And that was the beginning of Greedy Cat.”

While early reader books remain the focus of her prolific output, Joy is also working on an adult novel with the musical working title Planning for Stravinsky.

“I won’t say too much about it except that it is set in a retirement village over three days in which some residents are trying to organise transport to Wellington to hear the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra play Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. The story will be funny, wise, sad and very physical,” she reveals.

For now, the simple pleasures of knitting jerseys and crafting unique gifts from her lathe are filling her downtime as she steps out of the public spotlight.

Tells Joy, “My focus is caring for Terry. That’s the most important thing. Everything else gets fitted around it.”