At 31 years old, actress Lena Dunham has had a hysterectomy in an attempt to end years of chronic pain that she has suffered due to endometriosis.

The former Girls star revealed in an essay she wrote for the latest American edition of Vogue that the decision to remove her uterus was made after many years of trying other options.

But after a decade of suffering chronic pain, undergoing mulitple surgical procedures and trying countless alternative treatments including pelvic-floor therapy, massage therapy, pain therapy, colour therapy, acupuncture, yoga, “and a brief yet horrifying foray into vaginal massage”, what other options remained?

Dunham has been hospitalised at least three times in the last year for endometriosis. Last April, she underwent surgery to separate her ovaries from her rectal wall. Afterward, she had considered herself endometriosis-free. But in May, during her appearance at the Met Gala in New York, she was rushed to hospital with complications and subsequently had to cancel her nationwide Lenny IRL tour, telling fans she was “in the greatest amount of physical pain that I have ever experienced” after doctors discovered more endometriosis.

Radio NZ journalist Susie Ferguson has also had a hysterectomy to treat her endometriosis.

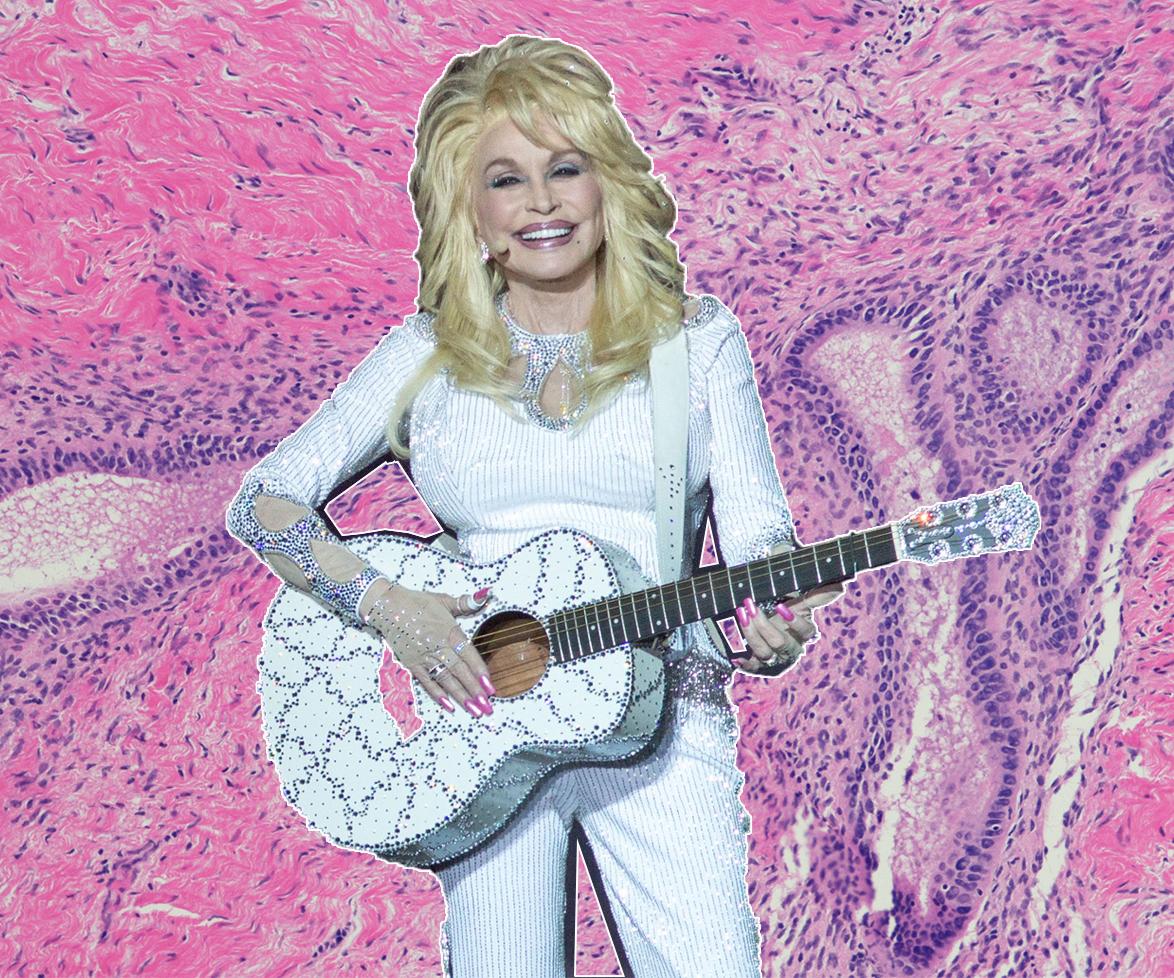

Endometriosis is a condition that affects one in 10 women and girls worldwide. It occurs when tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside of the uterus. Symptoms can include chronic pain and, in some cases, lead to infertility.

In the latest issue of The Australian Women’s Weekly Radio New Zealand broadcaster Susie Ferguson opened up about her three-decade struggle with the condition, which eventually led to her undergoing a laparoscopic hysterectomy.

“It’s life-changing. I’ve had no pain for weeks now,” she shared in The Australian Women’s Weekly.

Dunham’s ovaries were not removed as part of the surgery and she is optimistic of a future where she can possibly have children.

In Vogue she writes, “I may have felt choiceless before, but I know I have choices now. Soon I’ll start exploring whether my ovaries, which remain someplace inside me in that vast cavern of organs and scar tissue, have eggs. (Your brain, unaware that the rest of the apparatus has gone, in theory keeps firing up your eggs every month, to be released and reabsorbed into the cavern.) Adoption is a thrilling truth I’ll pursue with all my might. But I wanted that stomach. I wanted to know what nine months of complete togetherness could feel like.”

Endometriosis: the confronting facts

One in 10 girls and women are affected by endometriosis worldwide, with symptoms usually starting in the teen years. As well as painful periods and infertility, other common symptoms include bloating, IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome) type symptoms, painful ovulation, unexplained bleeding, pain during or after sex, fatigue and pelvic pain.

There are some cases where women show very few symptoms of endometriosis, and it’s only discovered when they struggle with infertility. It’s believed that 50 per cent of infertile women have the chronic disease.

On average, it takes more than eight years to be diagnosed from the first sign of symptoms.

It’s a billion dollar problem in New Zealand. It costs the country $1.2billion each year in public health costs, including surgical and medical expenses. This number doesn’t take into account the “hidden” costs on mental health, lost productivity at work and the burdens on individuals and their families.

According to Southern Cross Healthcare, endometriosis is the most common private surgical healthcare claim for women.

There is no known cure for endometriosis; the three main treatments are medical, surgical and symptom management with various therapies.

The symptoms do not correlate with the stage of disease. You can have mild endometriosis and severe symptoms.

Hysterectomies are not a cure for endometriosis. Some women may choose this option when other treatments have failed but further treatment will need to be considered if the symptoms return. Surgical treatment should remove (excise) the endometriosis. A hysterectomy treats adenomyosis which affects the muscle of the uterus and many women have this condition as well as endometriosis.

There are several theories about what causes endometriosis, and a strong genetic link – if your mum, grandmother or sister had it, there is a higher risk you might as well. Keep in mind that even if they weren’t diagnosed with it, it doesn’t mean they didn’t have it – for decades, endometriosis has been written off as “just bad periods”.

Last December, Australian Health Minister Greg Hunt formally apologised to women with endometriosis, admitting that the crippling condition should have been acknowledged earlier, and announcing the creation of a National Action Plan with immediate funding dedicated to research, education and awareness.

Early recognition of symptoms and early appropriate intervention are vital.

For more information, visit Endometriosis New Zealand at nzendo.org.nz.