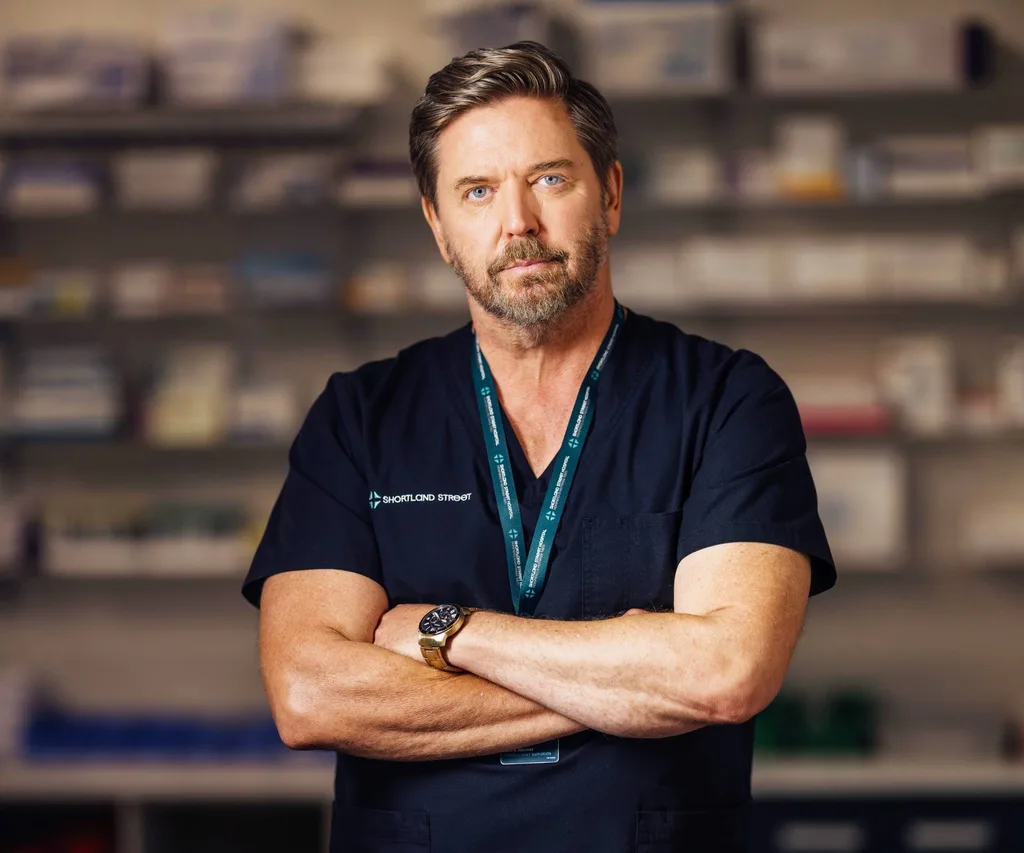

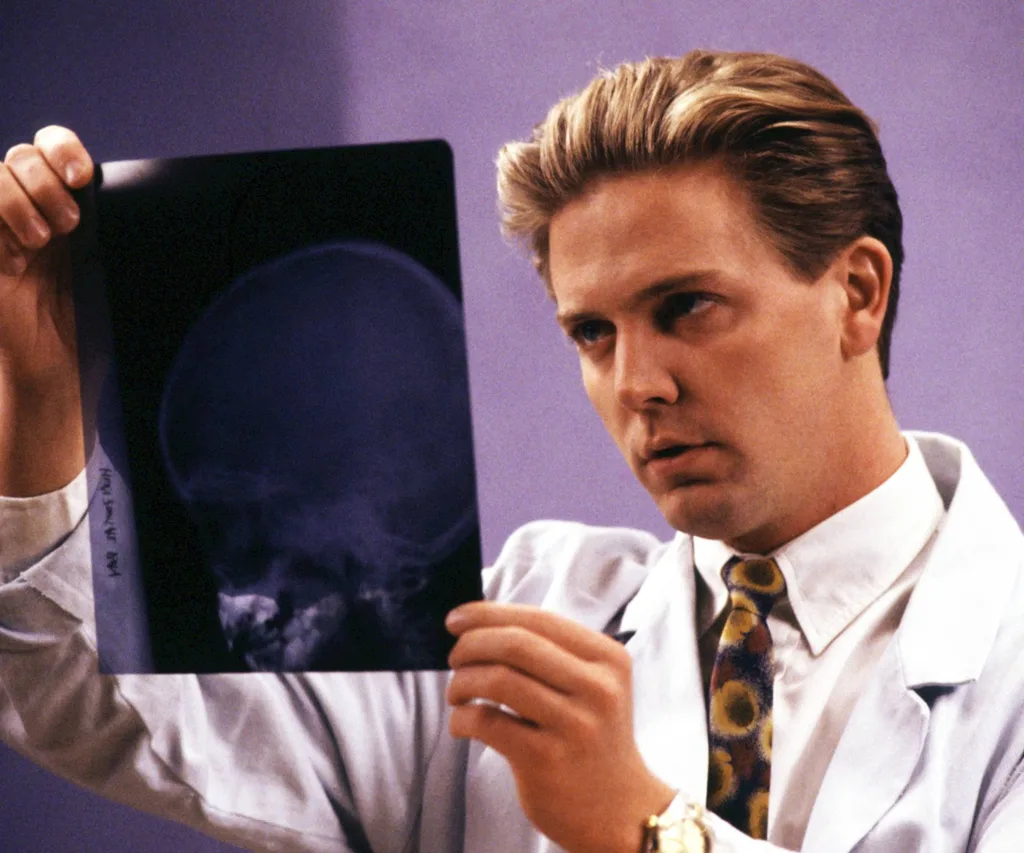

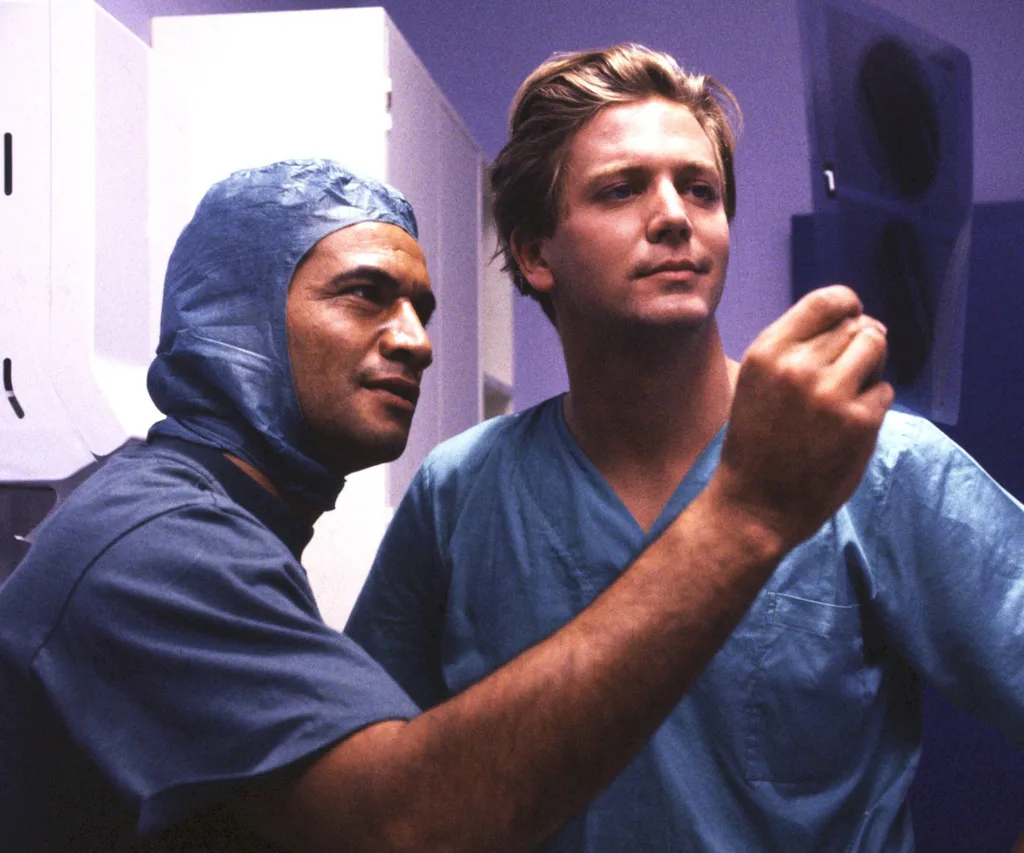

Michael Galvin holds the New Zealand record for being the longest-serving actor in a soap opera. A graduate of Victoria University and Toi Whakaari: New Zealand Drama School, he has played Dr Chris Warner on Shortland Street for more than 30 years. Alongside his successful screen career, Michael is a talented stage actor, musician and an award-winning playwright. But if acting hadn’t worked out, Michael, 60, says plan B was computer programming. Fortunately for his fans, he never had to take that route.

I was born in London because Dad was an economist working for the government and he was posted there.

Which is very cool because it means I have a UK passport. But we came back when I was two, which was also cool as I had a very pleasant childhood in Khandallah in Wellington.

I have two brothers and a sister

And apparently, I’m a classic middle child in that I’m an appeaser. It was a very Catholic upbringing. We went to church every Sunday and I was big in youth group, but I’m not religious now. My stepmother has a great quote, that a Catholic upbringing is a great immunisation against being religious in later life.

I do still have a spiritual side.

I read a lot of Western interpretations of Eastern spirituality. Writers like Michael Singer and Eckhart Tolle are basically about trying to free ourselves from being slaves to our thoughts and feelings. Which is about being present without a big narrative. It’s like a Western version of Buddhism and it’s helped me through life.

I was a very well-behaved child.

I was also very good at singing, which is how I became involved in musicals. All that attention, people applauding and telling you you’re wonderful, that’s where I got my taste for acting and being on stage.

At Raroa Normal Intermediate, a woman called Anne Fox was in charge of musicals.

She cast me as Oliver when I was 11. Oliver! was my gateway drug for theatre and it’s been downhill ever since!

I was never compelled to be naughty.

Mum was a social worker and a psychologist who’d talk with us about absolutely anything. Both parents were open-minded and we were never forbidden from doing things, so there was nothing for us to rebel against. Which is how I’ve tried to bring up my own daughter, by keeping the channels of communication open. I could also see the logic of not smoking behind the bike sheds.

For holidays, we rarely went further than the Kāpiti Coast, unless we were visiting our great-aunt and uncle in Meadowbank.

It’s still so exciting to think about those trips, as Auckland was such a magical destination. We had this big Fiat station wagon and we’d drive through the night or leave very early. My little brother Pete and I would be fast asleep in the very back with no seat belts, which is hilariously unsafe to imagine now.

Mum had a strong creative bent.

She played the piano and told lovely stories. Including about her own mother, who was a theatre usherette with a great ear for music. My grandmother would watch the movies, for example, a Fred Astaire film, then go home and play the songs she’d heard for all her friends. That was life before Spotify, but nobody in our family had pursued the arts professionally before.

Dad was very successful.

He was Secretary of Treasury and head of the Prime Minister’s Department when Muldoon was PM, so the peak of the civil service. Dad was also very encouraging and whenever I sang or was in a play, he was very sweet and effusive in his praise, as the arts were so alien to him.

I did a Bachelor of Arts at Victoria and, as a homage to my father, I did commerce, but I quickly dropped it because I had no enthusiasm for it.

Dad was supportive but like all parents, he worried for my job security. The landscape for actors was very different pre-Shorty. Back then, most actors worked in theatre, which didn’t pay very well, so he was right to be worried, as any parent should be when their child says they want to be an actor.

I was with a great bunch at drama school.

Marton Csokas and Cliff Curtis both have big international careers. Tim Balme, Emily Perkins and Sima Urale were there too. Although the first time I applied, I didn’t get in. I found out later it was because one of the tutors thought my degree would make me close-minded and unable to accept new ideas. I was hugely annoyed, but the second time I auditioned, they managed to get over that bias.

When I did Blue Sky Boys with Tim Balme, a musical about the Everly Brothers, we all went out to dinner afterwards.

I remember Dad shaking head as he couldn’t believe how much he enjoyed it and how impressed he was. He was very supportive and loving, in his way.

Dad died in 2010.

Although Mum is still with us, she’s in a dementia ward. She knows who I am and the staff take such good care of her, but that is a different kind of journey.

I’ve been on Shorty for more than 30 years now.

I was off for four, from ’96 to 2000, and I was scared to return when I got the call. Worried I’d look like a failure and that people would be negative or make fun of me. Because I’d supposedly left Shorty to find my fortune and instead I was crawling back with my tail between my legs, but the reaction was mostly very kind. There were a few sarcastic comments from some reporters, like, ‘Oh, he’s got a fake English accent’, but nothing like I’d imagined.

Being away and coming back made me appreciate what a blessing this job is.

How lucky I am to have this stability. We work incredibly hard to make Shorty and I’m always meeting new people, which is wonderful. This job is like the mighty river that’s always changing, yet always staying the same.

During my four years away, I tried Sydney but that didn’t work, then my partner at the time, artist Emily Wolfe, won a scholarship to the prestigious Slade School in London, so we went there.

I had my UK passport, but I couldn’t get an agent. They didn’t need New Zealand actors trying to do English accents as they had English people who could do English accents.

That was definitely tough and demoralising that none of my hopes panned out.

But that was London for me. Doors shut in my face and I couldn’t get any traction. But my writing developed and got stronger, and I did sell a screenplay. Although it never went anywhere, but I was paid proper money and that lifted me out of feeling like a failure. A little success goes a long way, but I don’t really write now.

When I did write, I had a lot of personal stuff to work through.

That was the compulsion. This tension that needed releasing, but I’m calmer and happier now, and that engine where the stories come from is less productive.

I do very little when I’m not working.

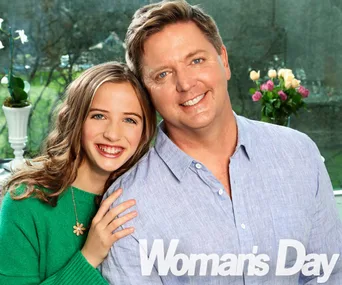

I have two cats, but they don’t take much looking after. I love spending time with my daughter, although she’s at university now. I’ve loved hanging out with her over the holidays. But you do have to be vigilant as a parent, to remember you’re not dealing with the person they were a year ago, as they change such a lot, but that is also a joyful thing.

I’m very spoiled.

I’ve got a lovely job where I engage with people in an energetic, creative way, including lots of young people. But I expend a lot of energy at work, so I enjoy the luxury of being by myself and doing nothing when I can. I enjoy solitude. I meditate, which is such a peaceful thing. The appreciation of quiet, of silence, of emptiness, for want of a better word. But the good sort of emptiness that you appreciate more as you get older.

I don’t torment myself as much as I used to or beat myself up.

My ambitions are much simpler. They’re more about what sort of person I want to be and I’m more in control of that than external things. That’s the standard course of life. Young people often focus their ambitions outwardly, chasing achievements and material success. If you’re lucky, your ambition shifts to a different plane and becomes more about what sort of person you want to be. But I’ve still got a long way to go.

Looking to the future, I’d like to continue to make Shorty, as it occupies such a special place in the nation’s landscape.

I never take this job for granted, either. I hope they keep making it and they keep finding a place for dear old Chris.”