Education Minister Hekia Parata steps through the towering glass doors of her modern beachfront home, brushing the sand off her feet. Even without the power suit she’s known for wearing in the Beehive, she cuts an elegant figure.

To most of us, she’s the Minister of Education. But when we meet her, she wants to be known by her first name. “Call me Hekia,” she insists with a warm smile. Born and bred in the tiny East Cape community of Ruatoria, Hekia entered politics with an impressive pedigree and was once tipped to be Prime Minister.

Her great-great-grandfather Tame Parata was an MP for Southern Maori for two decades and she grew up strongly influenced by the great Maori leader Sir Apirana Ngata.

But in a shock move, Hekia, 58, last month announced she would not be standing in next year’s election. Known for her work ethic, she says she has given a decade of her life to politics. “Ten years is about the right parabola for this sort of job.”

Normally a fiercely private person, as she sits down with Woman’s Day Hekia is sharing for the first time her very personal story. While she’s had job offers, she has no immediate career plans. “I literally do not know what I’m going to do next,” she laughs.

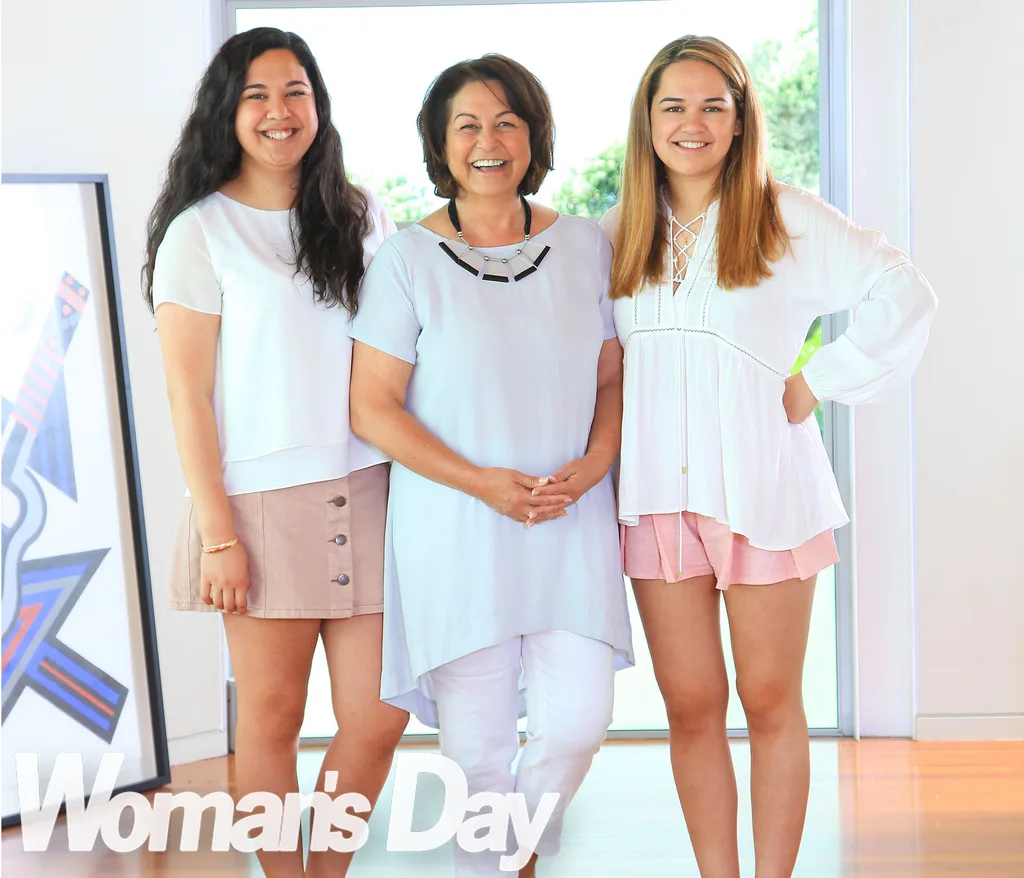

Despite rumours, she insists her husband Sir Wira Gardiner, 73, is not sick. “Wira is as strong as an ox.” This summer, the National MP plans to recharge and consider her options, with her husband and their daughters, Rakaitemania and Mihimaraea, who are both in their 20s and studying at Victoria University in Wellington.

Hekia and her gorgeous girls make a tight trio. Whatever city she is in, she sends them messages first thing in the morning and last thing at night. “I love my daughters beyond belief,” she says.

Their stunning house in the sand dunes at Wainui Beach, near Gisborne, was bought six months ago as a more permanent home. After years of dividing their lives between cities, Hekia

and Wira craved a private oasis for their family.

She laughs, “Of course, I came to the auction for the house and everyone whispered, ‘There’s the Education Minister.’”

The third of eight kids and the eldest girl, Hekia is still known to her whanau as “Sis”. She tells, “I was the decision maker, the peacemaker in our family.”

Hekia’s dad Roslyn “Ron” Parata was deputy principal at Ngata Memorial College in Ruatoria and the family lived in a three-bedroom Ministry of Education house just off the main drag.

“To my country cousins, it was the CBD,” laughs Hekia. The Parata children were encouraged to work hard, serve their community and strive for success. Education, though, trumped everything.

Her father, who passed away in 2002 at 82, encouraged his children to be clear thinkers. “He was intolerant of stupidity.” Ron fought in the Maori Battalion before training as a teacher. “He was counter-culture,” says Hekia. “He broke barriers. He told us, ‘Don’t let anyone tell you how to think.’”

According to family legend, he rode a motorbike up from the South Island in the early 1950s. “Dad burst into Ruatoria in his leathers,” recounts Hekia.

Her mother Hiria Reedy was said to be playing tennis when she caught the young soldier’s eye. Hekia’s voice still catches when she talks about her mum.

Hiria lived with Hekia and her family before she passed away in 2009. “Mum was a sort of Pied Piper for kids in Rua.”

Hiria instilled in her children a love of language. Her own – te reo o Ngati Porou – as well as English. She encouraged Hekia and her siblings to learn six new words every week.

Hekia tells, “I remember sitting under the clothesline as she pegged out the clothes and spelled out ‘rumination’.”

Hiria, who established Playcentre on the East Cape, had her own ideas about education. Hekia recalls her mother throwing Rakai and Mihi’s colouring-in books across the room, saying, “My grandchildren will not be confined to someone else’s view of the world and draw inside someone else’s lines!”

Hekia tells how she loved school and sat in the front row of every class. “I guess you could call me a geek.”

At the University of Waikato, she was president of the students’ union and worked nights in a bar to fund her Masters degree in Arts. She didn’t have a career plan but knew she needed to be ready when opportunities arose.

Her decade in public service began with Foreign Affairs and a posting to Washington DC. Hekia was working for Housing Corp when her brother Selwyn suggested she apply for a job at Te Puni Kokiri.

“He said, ‘Call the new chief executive, Wira Gardiner.’ I said, ‘Never met him.’”

Hekia phoned to talk about a meeting. “Then he hung up on me – without saying goodbye,” she laughs. “I know now that’s what Wira does when the conversation’s over.”

Wira was a soldier before entering public service. In 2008, he was knighted for services to Maori. Hekia describes her husband as “his own person” and a dad with unconditional love. He has three older children and seven grandkids from his first marriage.

“When the girls were little, if they wanted ice cream at 1am, they got it,” says Hekia, rolling her eyes. “He’s the best dad in the world,” adds Mihi. His many nephews and nieces call him “Uncle Sir”.

“Wira loves strong women,” says Hekia, smiling across at her daughters. “That’s the thing that first attracted me to him.” In 1993, the couple married in Te Horo on the East Cape, the childhood home of Hekia’s beloved mother. Their careers in public service beckoned and they returned to Wellington to work.

When Mihi was newborn, Hekia had an urge to return to the coast. “I looked at Wira and said, ‘Let’s go home.’ We packed up the car like the Beverly Hillbillies. “We had nowhere to live and no jobs. We bought a section in Ruatoria and moved on a kitset home. All I knew was that I wanted my girls to grow up at home.”

Hekia wrote social policy for local and international clients, and the couple started their own consultancy company. “No-one knew I was working at an old school desk in my Ugg boots,” recalls Hekia.

The girls attended a decile-one Maori-immersion kura kaupapa and grew up among whanau. They spoke little English until they were about seven. “It was the best decision we ever made,” insists Hekia.

With seven siblings within a 1km radius, Rakai, Mihi and their 22 cousins rotated around households each weekend.

“We had the best childhood,” says Mihi. “It was the best of both worlds.”

In 2002, Hekia stood as the National Party candidate for the general election. Why National? She explains, “We share important values – getting government out of people’s lives so they can occupy them instead.”

She didn’t make it to Parliament that election and didn’t stand the next, but was finally elected in 2008 as a list MP. “People couldn’t figure us out,” Mihi recalls of their move to Wellington.

“We were too Maori for Pakeha and a bit Pakeha for Maori. We can go from red bands at the marae, to high heels at the Beehive to see Mum.”

Hekia was appointed Minister of Education in 2011 and it was a baptism of fire. She has referred to 2012 as her annus horribilis. “If anything could go wrong, it did.”

She arrived in the aftermath of the Christchurch earthquakes and inherited the Novopay debacle. She copped flak for larger classes, closing schools and her idea of online classrooms. Hekia was called “divisive” and “public enemy number one”.

She tells, “I remember driving along the Desert Road during the 2012 maelstrom and Bill English called to see how I was coping. I said, ‘I haven’t read a newspaper for a week.’”

Hekia says the resilience encouraged in her as a child saw her through, as did support from her whanau. She is stepping away confident that New Zealand has a “world-class education system”.

“I am a big change agent and those changes need time to settle,” she insists. “What’s needed next is someone with a different set of skills.”

Hekia says she has given “200%” to the job, driven by a desire to create opportunity and choice for all young people. She’s proud that 79.1% of all school leavers achieved at least NCEA level 2 last year – an 11.6% increase on 2009.

While she doesn’t know what the future holds, for her, that’s the best part. “I have never known what chapter lies ahead in my career,” she explains.

Hekia has vowed to learn stand-up paddle boarding and is planning long walks on Wainui Beach with her family. She and her daughters are avid readers and she has books to swap with them.

“I’m excited about the little things, like standing in line at the supermarket without being recognised,” she jokes. For Rakai and Mihi, their mother’s move from the limelight hasn’t come a moment too soon. “I’ve been telling her to quit for years,” says Mihi.

Adds Rakai, “I’m just looking forward to you having more time for you, Mum.”