Westside hit Kiwi television screens with a bang last year. Set in the 1970s, it tracked the origin of the notorious fictional West family, who were at the heart of Outrageous Fortune’s six-series sensation.

The second season of Westside takes us back to the early 1980s in New Zealand. A time of big hair and bold eyeliner, moustaches and tight pants, the music of Dave McArtney & The Pink Flamingos, shrimp cocktails and a government led by the cantankerous Rob Muldoon.

It was also an era when New Zealand experienced its greatest civil unrest since the 1951 waterfront dispute.

The producers of Westside couldn’t truly represent the time without covering the infamous protests of the 1981 Springbok tour, when thousands of New Zealanders rose up against the decision to host a rugby team whose government supported apartheid.

The show’s storyline is rich with the drama of that tour, using cleverly interspersed historic footage of the Hamilton pitch invasion (which shut down the second game of the tour) and the Eden Park protest where flour bombs were dropped from planes.

It was just 56 days in our history, but those days marked a major milestone for New Zealand. They have been described as the time New Zealand first took responsibility for its place on the world stage. More than 150,000 people participated in more than 200 demonstrations in 28 centres, and 1500 were charged with offences associated with the protests.

Core Westside cast members Antonia Prebble and Sophie Hambleton each have a strong family connection to the protests – stories they share with The Australian Women’s Weekly. And activist John Minto talks about being at the forefront of the civil disobedience.

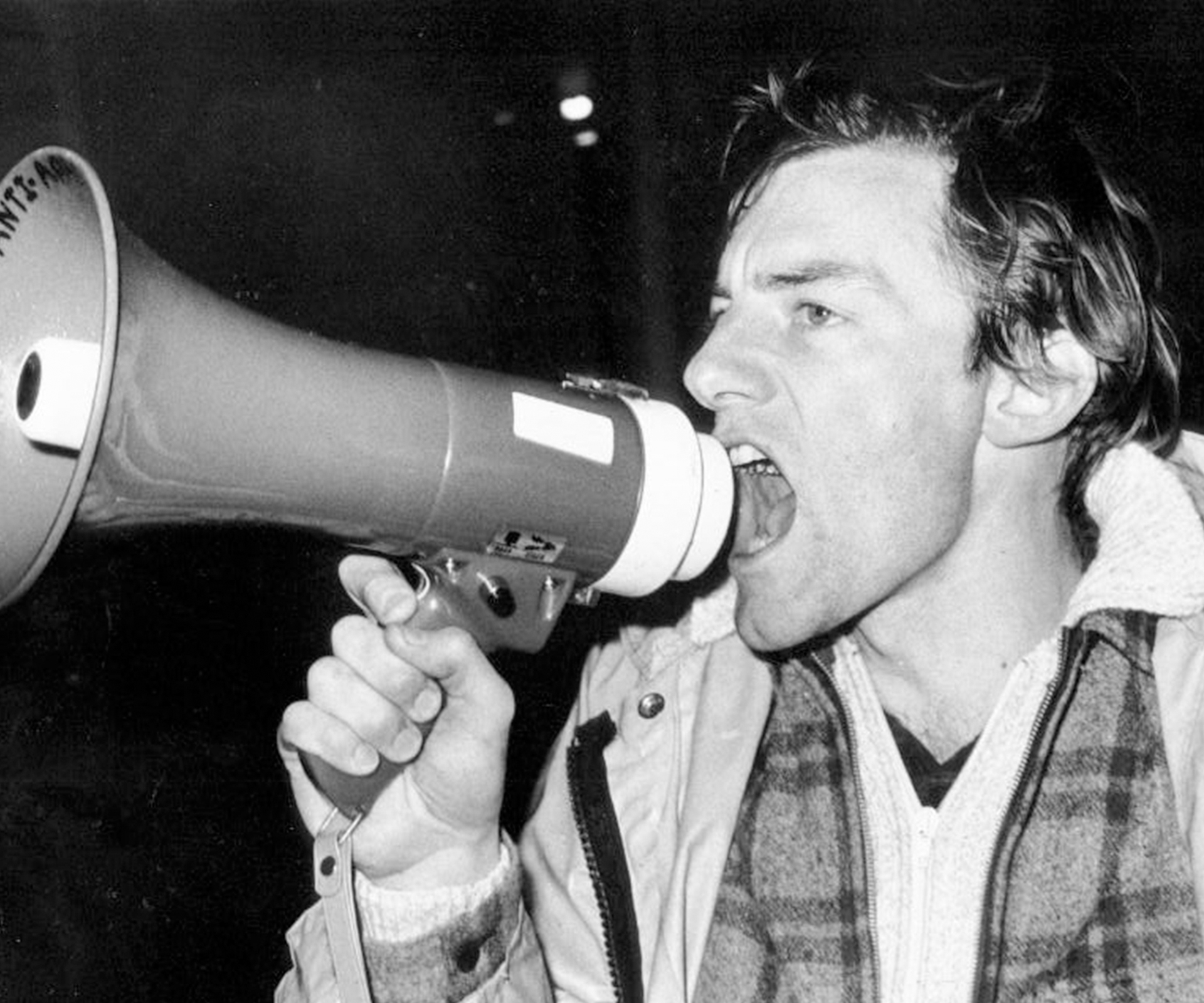

John Minto voicing his protest to the Springbok Rugby Tour in 1981.

John Minto joined HART (Halt All Racist Tours) in the mid-1970s in Napier. In 1977 he moved to Auckland and became secretary of the protest group. He was a pivotal force in the organised movement against the Springbok tour.

I got involved in [anti-Springbok tour action] because it was an important issue and one in which I thought New Zealand could punch well above its weight. We had the most important international link that white South Africans wanted – rugby and the All Blacks, and we knew we could make a difference.

We started the planning and organising almost two years before the Springboks came. Initially we focused on shifting public opinion. By the time the Springboks arrived, we had moved public opposition to the tour from about 15-20 per cent to 45 per cent. That was through educational work, film screenings, public meetings, petitions, public events and deputations.

When it became obvious the tour was going to go ahead, all of the planning went into the protests.

Early in the year we had a training camp in Auckland where people came from all around the country to do some basic civil disobedience training. We had men and women and people of all ages on those marches – from babies in prams to grandparents.

The protest in Hamilton [when protestors stormed the pitch and stopped the game] was quite deliberate – we knew we could get large numbers of people there from Auckland. I went down with a group of people first to look at where we might be able to break into the ground. Then on the Saturday we brought bolt cutters, ropes and clip-ons to break through the fences but in the end people just grabbed hold of the wire mesh and peeled it away like a banana.

After the game was called off it became absolute mayhem. People on the field were being attacked as they left – I got hit in the head by a full can of beer and knocked unconscious. A pensioner who lived across the road from the park brought 15-20 of us into his house without a second thought – there was a big ugly mob outside, baying for blood.

I walked out with a towel over my bleeding head wound to get into an ambulance and someone yelled, “There’s Minto – let’s get him!” We had to go back inside and have the ambulance come back an hour later. Everybody sat on the floor below the windows so we wouldn’t provide any provocation. It was pretty scary.

People were bashed willy-nilly around Hamilton that night – anyone who had a ‘Stop the tour’ sticker on their car was stopped at traffic lights and dragged out of their car. We had our own medical team and the vehicle they were using was attacked and a couple of people were dragged out of the back of it. We were incredibly lucky no one was killed.

We had been on the field chanting “The whole world’s watching, the whole world’s watching” and hoping like hell that they were – but the impact in South Africa was far more than we had anticipated. It was the very first time ever that a rugby game was televised live from New Zealand. South Africans got up in the middle of the night to watch the game and all they saw was protestors – white South Africans were furious and black South Africans jubilant.

Nelson Mandela, who was imprisoned on Robben Island at the time, later told Dame Cath Tizard that news of the game being called off because of anti-apartheid protests went around the prison like wildfire. They grabbed the bars on their cell doors and rattled them right around the prison. He said it was like the sun came out – here was a little country on the other side of the world where people were creating a huge blow to the apartheid regime.

It rocked New Zealand out of complacency about international events. We saw ourselves as a small, insular country at the bottom of the South Pacific, not beholden to anyone, but we were forced to realise we were part of a much bigger international community.

And it knocked our complacency about race relations in our own country. By 1985 the New Zealand Labour government gave The Waitangi Tribunal the power to look at historical treaty grievances and that started off a whole process, which I think has been a very healthy one for New Zealand. The debate that took place at the time was a big part of making that happen.

Antonia Prebble, 32, plays Rita West. Her mother, Nicola Riddiford, was involved in the march to parliament in Wellington on July 29, which turned violent. In Auckland, Antonia’s grandparents set up a makeshift hospital outside Eden Park during the September 12 match, to care for injured protestors. At that match smoke and flour bombs were dropped from a Cessna aircraft inside the grounds and police and protesters came to blows outside.

My father’s parents lived really close to Eden Park. My grandfather, Kenneth Prebble, was an Anglican minister and the vicar of St Paul’s on Symonds Street, and my grandmother, Mary Prebble, was a nurse.

There were some terrible injuries inflicted on protestors during that Auckland match and my grandparents set up a casualty clearing station on their front lawn to tend to them. They were liberal people and very into social justice. I am so proud of them, and I am so glad they were on that side of the fence.

My mum was six or seven months pregnant with my [older] sister at the time of the Wellington protests. She wanted to be involved because she felt so strongly about it, but she was also very aware of putting her unborn child in any danger. She marched most of the way there, but as things got more aggressive she pulled out, in case it erupted into violence. She said it was a pretty charged atmosphere and a crazy time to be in New Zealand.

My character in Westside, Rita, is not politically motivated at all – she is more interested in how she can take advantage of the situation for her own gain, but I’m 100 per cent sure I would have protested if I had been there. Apartheid is horrific and it would have been an opportunity to stand up against something that I fundamentally disagree with.

There is that saying that evil happens when people do nothing, and I believe if you have an opportunity to stand up to something you believe in, you should – particularly if it is on your doorstep.

I have never been involved in anything like that, so I don’t know how I would have coped with it – I can’t imagine I would have got into any fighting, but who knows!

Sophie Hambleton, 31, plays Carol O’Driscoll. Her aunt, Tulip Hambleton, was on the march that took place on August 29 when 7000 protesters gathered in central Wellington and blocked vehicle and pedestrian access to Athletic Park.

My Aunt Tulip was on the march against the Springboks that blocked the upper motorway in Wellington. She remembers looking around her at the crowd and feeling really proud and invigorated that so many people thought this was an important enough issue to physically attend.

She told me how united they were as a collective. She said the violence and chaos that erupted didn’t come from the protesters originally; they were just trying to stop the games from happening, which they did.

I guess at the time they didn’t think they were being particularly brave – they were a mass group of people taking action on an issue they believed in, but so many people did get injured. I would have been terrified.

My Westside character Carol represents a small portion of New Zealand that the Springbok Tour passed by, or maybe no one bothered to ask her opinion – she was much more interested in the royal wedding of 1981!

I acted recently in the tele movie Rage, about the protests, and played a young protestor who was batoned by the police in one of the marches outside parliament. It was such an emotionally fuelled issue – people panicked, the police panicked. We are a country so obsessed with rugby – it is so important to people that grown men cry and our domestic violence rates increase around Rugby World Cup time.

My mum was living in Sydney at the time of the protests and when she came back to New Zealand at the end of 1981 she was mortified – she’d had no idea how much people had been protesting and what was happening in New Zealand at the time.

Now we have social media and the internet and we know exactly what is going on in the world pretty much as soon as it happens. Back then, she was isolated from what had been going on and said she felt she had missed this huge movement that still really defines us.

It does that in a similar way to our nuclear policy – we are such a small country and the fact that a portion of our population could affect change is really incredible, and still something that is talked about internationally.

For my aunty, being involved in one of the bigger marches created a real sense of pride.They did stop games and they were able to have their voice heard internationally.

We roared loud for a small lion.

Westside screens on Sunday evenings at 8.30pm on TV3.