They are our brightest brains. Awarded the biggest trophy, written up in the local paper and immortalised in gold leaf on the school hall honours board. The dux. In Latin, it means “leader”. Simply the best.

This month, hundreds of students at colleges around the country will leave school with the title and guaranteed acceptance into virtually any university course they choose.

At Auckland Grammar’s senior prizegiving in early December, the biggest ovation, as always, will be for the dux – a sign of the respect for the title and the boy who wins it. “The cup for the dux is the biggest – no cup is permitted to be bigger than the cup for the dux – and it doesn’t matter what else has occurred in the school year, the applause for the dux is always the loudest,” says headmaster Tim O’Connor. “Academic success is number one and that’s what we hold tight to.”

Rivalry for the title is extreme and the race can be won or lost by the barest of margins – as little as 0.5 of a mark. Each boy, after each exam, knows exactly where he ranks. “When they sit in the scholars’ photo, they sit in rank order.”

Increasing numbers of the top students these days are heading for prestigious universities overseas, such as Oxford, Cambridge and Princeton, and O’Connor acknowledges the potential for the loss to New Zealand to be permanent. But he says that’s always been the case.

Otago University is trying to buck that trend. Since 2006, it has made a determined effort to attract duxes by offering a scholarship, now worth $5000, to each dux who studies there. More than half the 80 duxes who enrolled this year went into medicine and a fifth went into science.

Otago deputy vice-chancellor Professor Vernon Squire says the university wanted to attract the best scholars. “We know that the duxes we bring into university perform better than other students in general. The pass rate for duxes in the first semester this year was 96 per cent, compared to 82 per cent for other students.” But he says it’s not just about academic prowess; duxes are usually “very well-rounded individuals”.

To mark this month’s round of prizegivings, we trawled the dux lists of a dozen high schools from the 80s and 90s – from decile one to decile 10, from co-ed to single sex, from state to private, and religious to secular.

Medicine, predictably, featured prominently among the chosen careers. At Grammar, for example, of the six duxes we were able to trace from the 1990s, all became doctors.

There were other trends, too, including the dominance of Asian names on the lists from the mid-1990s, a surprising number of siblings gaining the same honour in different years, and the emergence of IT over more traditional professions as a prime career option for the seriously smart. And there were stories of young talent cut tragically short, like the King’s dux of the mid-1980s who was dead two years later, or those who never fulfilled their potential because of physical or mental illness.

So, does being a dux count when the studying is over? And for how long does it hang around on a CV?

We found out what life had in store for six former duxes, now in their 30s and 40s.

Nick Cutfield with his dux medal, above main image Dr Nick Cutfield in his medical practice office.

Nick Cutfield

OTAGO BOYS’ HIGH SCHOOL

Class of 1992

From his early months as a baby in a cardboard box in the Oxford University research laboratory of renowned chemist and Nobel Prize winner Dorothy Hodgkin, Nick Cutfield was destined for a career in science or medicine.

His mother, Sue, was completing her PhD, and his father, John, was doing his post-doctoral research. For baby Nick, it was akin to hitting genetic bingo. By the seventh form in 1992, he was not only dux of Otago Boys’ High School, but also competing in the NZ Chemistry Olympiad.

Cutfield, like most of the duxes we spoke to, says he wasn’t much of a swot – with these sorts of brains, prizes and top marks seem to come easily. He says medical school, where he had to learn so many facts, was far more difficult than school, where the emphasis on maths and the physical sciences was on learning as few facts as possible but working things out from first principles.

“If you’re strong in the sciences and you’re also a good communicator, then medicine is considered a good option in New Zealand, whereas in, say, North America, Europe or the UK, there’s a greater range of industry and that’s not necessarily the case.”

He was quickly drawn to neurology. “I always had an interest in clinical neuroscience but when I was studying for the specialist physician exams, preparing for the neurology part was more challenging because you needed to adapt your strategy, to think more and solve more difficult problems, so I enjoyed that challenge.

Cutfield, 40, a consultant neurologist at Dunedin Hospital, is now a father of two, and married to a biochemistry research fellow. He says he’s making an effort to enjoy other parts of life apart from work and study, “like seeing my kids climbing some mountains”.

That well-rounded approach was also apparent at school, where he performed in school productions and music groups and played club tennis.

While his school peers are spread around the globe, Cutfield says he always intended to return home, and did so five years ago, after four years in London.

Yes, he says, he was happy being dux. “But did it change things hugely for me? I don’t know. After you’ve been out of school for a while, the CV starts to drop off those high-school achievements.”

Vaughan Smith at Facebook headquarters in Menlo Park, California.

Vaughan Smith

CHRIST’S COLLEGE

Class of 1984

If you opened Facebook on your mobile today, former Christ’s College dux Vaughan Smith is one of those you have to thank.

The son of Southland farmers, Smith says his parents made real sacrifices to send him to board at the prestigious school in 1982. He repaid them by leaving as dux in 1984. Thirty years on, he’s a vice-president at Facebook’s California headquarters in Menlo Park and in regular contact with founder Mark Zuckerberg, one of the world’s richest and most influential men.

Zuckerberg once said the company acquired people, not products. So it says much for Smith that Zuckerberg not only acquired him but also put him in charge of acquiring others. Smith was one of the people Zuckerberg entrusted to lead Facebook’s move from a desktop to a mobile company. It was a “huge transition”, says Smith. “The aim was to make our mobile products fantastic. They used to suck.”

Smith, 47, has come far since he graduated from Canterbury University with a PhD in electrical engineering. Like his stellar school results, it was achieved with little observable effort. “My flatmates, who were trying to give me career advice, literally took me aside and said, ‘Look, you’re such a bum, you’ll probably never get a real job.’”

Despite the heft of a PhD behind him, Smith did a career u-turn on leaving university in 1992, going into investment banking. “I had multiple job offers to do engineering but when I talked to my predecessors, they didn’t seem as excited about their jobs or to be having as much impact as the people I talked to in investment banking.”

He says he was taken on as a good all-rounder, despite having no experience, and having “dux” on his CV, he says, “sure didn’t hurt”. While the title becomes less important as time passes, it always counts, Smith believes. “You’re always looking for signs that people can excel. And being the best at something is a good sign that people are capable of excelling.”

Vaughan Smith with his parents, Southland farmers, on graduation day at Christ’s College.

After four years in investment banking – a job he grew into after initially struggling with the “huge handicap” of having no background in finance or economics – he was headhunted by Telecom. He was hired as head of strategy to work with then-CEO Rod Deane, despite being told he had no experience and was 15 years too young for the job.

Smith was at the telco for four years, and during that time set up a new group to provide e-commerce services to business – and met his interior designer wife, Bridget McIver.

In 2000, the couple took a year off to travel the world, before settling in Silicon Valley, California. “I’d always wanted to come here – it’s where the action is. I decided I wanted to be a CEO of a technology company.” He had no qualms about knocking on doors and selling himself, saying his time at Christ’s gave him “an expectation that I could be the best, an expectation that you could do anything you wanted to do”. His confidence worked; he was given the CEO position at LiquidWit, a company he describes as “like an eBay for professional services”.

The company failed about a year later, which he took hard. “It was about 10 years ahead of its time. I want people to be clear that I’ve always made plenty of mistakes and got knocked down, but you always get up because you think you can be successful, and that goes back to the mindset that was created at Christ’s College and I credit the school with doing a phenomenal job on that.”

After LiquidWit’s failure, Smith joined eBay in a leadership role, becoming one of the company’s first 15 vice-presidents. “At the time I joined, it was the hottest company in the valley. It was making a lot of money and growing really quickly. People with talent who were looking for jobs wanted to work at eBay, so the people I was lucky enough to join with were really strong. I met so many great people, and have friendships I continue to cherish.”

In his six years there, he led internet marketing, managing a budget of several hundred million dollars, and ran the acquisition of PayPal, which he says has been described as one of the most important technology acquisitions in Silicon Valley.

Departing eBay in 2007, Smith then joined a real estate company, trying to turn it around by moving its business online. “I failed. I was just too optimistic that I knew the right answer about the strategy and didn’t pay enough attention to the signs the strategy wasn’t quite right. I regard it as a personal failure because I wasn’t successful doing what I joined the company to do.”

Since 2008, Smith has been at Facebook and has taken a number of key roles, including attracting investment dollars during the Global Financial Crisis in a deal that has been labelled as heralding the start of the current bull market in Silicon Valley, and leading the transition from desktop to mobile. He’s now working on “strategic projects” he doesn’t want to speak about publicly but which are fresh challenges. “I get bored easily. I like solving hard problems.”

Despite an IQ likely to be in the stratosphere, he says he wishes he was as good a learner as his CEO Zuckerberg. “He’s incredibly gifted, strategic and a great person at the same time. And he’s a lot brighter than I am.”

Lawyer Deanne Burt

Deanne Burt

OTAHUHU COLLEGE

Class of 1992

The same year Nick Cutfield was picking up his dux award, Deanne Burt was graduating with the same prize from a school at the other end of the socio-economic spectrum – decile-one Otahuhu College in South Auckland. And, unlike the heady academic heights Cutfield’s parents achieved, Burt was a truckie’s daughter and the first child in her family to finish high school.

“I didn’t think I was especially clever, but I’ve always been a bit of a geek and enjoyed my schoolwork.” And, she says, she saw from an early age that a university education was her ticket out of South Auckland.

One of only four Pakeha in her seventh-form class, Burt says she enjoyed growing up in the area, although she was also aware of its problems.

“I don’t look down on South Auckland but it has a real set of challenges. It’s quite hard to find a way out, maybe, of the life that’s almost dictated for you.”

Her family – her father died when she was 15 – lived in Mangere. “You’d hear things like family violence in the neighbouring houses and see police cars visiting. I remember walking to catch the bus and carloads of people driving past and yelling out, trying to be offensive. I found it quite bizarre – I thought, what was their problem with me? I didn’t know them from a bar of soap. I didn’t find it scary, just bewildering.”

For Burt, her academic strength was in languages, geography, English and history. “I couldn’t do maths to save myself so I dropped it as soon as I could after School C. I was very aware of what my strengths were so I played to them.”

She says her parents could never have afforded a private school, but the disparity was hammered home when her class did a “trading places” day in the sixth form with neighbouring King’s College. “It was a real eye-opener seeing what they had. Each student had their own laptop and their music resources outweighed anything we had. I wasn’t resentful, because we always knew they were better off than us, but it was interesting to see what it looked like on the other side of the fence. It was kind of aspirational,” Burt says.

Becoming dux was a happy “bolt out of the blue” – she was in awe of those who were good at the sciences – but she felt it was also a validation for her hard work.

Deanne Burt (third row up, second in from the left) at decile-one Otahuhu College.

At Auckland University, she earned a BA in anthropology and history, then an MA in anthropology, specifically archaeology. “It’s very niche, very interesting, but not that easy to translate into a career.”

Not long after her MA, she met her future husband, a Brit, and went to London with him. She couldn’t get her dream job as a museum curator, but spent an enjoyable seven years in sales and marketing with Getty, the image library.

By January 2007, however, she had returned home and the academic itch was back too. Supported by her husband, she enrolled in law school at 31, completing her degree in 2012. “It was challenging. Very much so. I was used to free time and all of a sudden I had to devote that to reading, writing essays and studying for exams. It was a real shock to the system.”

Drawn to employment law, she gained a job in a small suburban general practice firm before moving soon after to the Employers and Manufacturers Association as an employer adviser, where she remains today. Her personal life, however, has been less settled. Her marriage broke up, she had a son in a new relationship and that partnership, too, has broken down. Burt, now a solo mum with a one-year-old, works four days a week, juggling the care of her son with the demands of a job where she advises EMA members on anything from redundancies and restructuring, to health and safety reform and discipline.

She’s hoping to further her career in employment law by appearing at the Employment Relations Authority and Employment Court representing clients – something she doesn’t do now.

Now 39, she says she still has aspirations, “probably even more so now because I have a child to think about. I wouldn’t say I’m extremely successful, but I’ve kept going, one foot in front of the other, trying to always look ahead to the future, always wanting to do well. Fear of failure is my big driver.

Yes, I’m proud of being dux. I’m pleased that I’ve done my best and that’s all I can do.”

Eletha Taylor in the operating theatre.

Eletha Taylor

DIOCESAN SCHOOL FOR GIRLS

Class of 1994

If King’s of the early 1990s was the top private school for boys in Auckland, its equivalents for girls were Diocesan and St Cuthbert’s.

In 1994, two years after Deanne Burt left Otahuhu College, Eletha Taylor was finishing the last of her 13 years at Dio as joint dux. “I think part of the reason I wanted to succeed is that I’m very black and white and had the view, especially then, that if you’re not the best at something you must be crap.”

Her parents – her mother was a nurse and her father a sailor in the merchant navy – “went without” to send her and her brother to private schools but their sacrifices have paid off, with both children now established in medical careers. Taylor is a breast and general surgeon in public and private practice, her brother Matt an anaesthetist at Middlemore Hospital.

She suspects she might not have become a surgeon without her private- school background. “Going to a single-sex private school, we had the luxury of it just being an assumption that you could do whatever you wanted.

“It was never explicit, just a constant sensation that I didn’t have to question whether or not I could do what I wanted.”

Surgery, she says, is a profession dominated by men but she never questioned her ability to join them. “I did see some colleagues who thought medical school would be a struggle and therefore it became a struggle.”

The pupil with whom she shared the dux award was a Chinese girl from Hong Kong who was at the school just two years and is now a high-profile lawyer in Beijing, a partner in an international firm.

Eletha Taylor at Diocesan School for Girls.

Like Smith and Cutfield, Taylor, 37, acknowledges her school achievements came relatively easily. “But that doesn’t mean I haven’t worked incredibly hard at other aspects of my life and, further down the track, the academic stuff didn’t just float out the end of the pen. Working full-time and doing the sub-specialty exams I did was horrendous and one of the hardest things I’ve ever done.”

Although she’s not on any crusade, she was probably subtly influenced to pursue breast surgery after her mother was diagnosed with breast cancer as Taylor neared the end of her medical school training.

She says her parents, despite not having the educational opportunities she and her brother had, “are two very intelligent people”. Her father’s two older brothers were doctors. “But in that generation you couldn’t go to university without parental support and, as the youngest son, I think he decided his parents were just not in a position to do it for him, so he left school at 16 and went to sea.”

Like Burt, Taylor works four days a week and is also coping with a demanding job and young child – her son is less than a year old – but she and her fiancé can share the load.

She suspects being dux has opened doors in her life, even if she’s not quite sure which ones. “Even 20 years down the track, being able to say you were dux… people recognise that as something a little different.”

More recently, she says, it’s coming up again as her brother and colleagues who want their own daughters to go to Dio visit the school and see her name on the honours board. “That stuff means a lot to me now.”

Phill Rendle at Victoria University’s Ferrier Research Institute and at Burnside High School (insert).

Phill Rendle

BURNSIDE HIGH SCHOOL

Class of 1989

You know, when you struggle to even understand Phill Rendle’s online job description, that you’ve got a seriously smart individual.

It says of the principal scientist at Victoria University-based Ferrier Research Institute: “Phill manages the custom synthesis, scale-up and process development work, linking to GlycoSyn’s cGMP facility. He researches dendrimers for pharmaceutical use.” Say, what?

No surprises, then, that Rendle, now 43, emerged as dux of the South Island’s largest high school, Burnside, in 1989. The biggest surprise is discovering, in a phone conversation, that not only is he un-nerdy, but he can also explain, simply and engagingly, what he does and why it matters.

Ferrier is involved with trying to develop new drugs, through the institute’s own research, and also helping other labs and biotechs to get their own discoveries to market. One, part of a newly approved medical device, is a gel put in condoms that provides a second line of defence against sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.

The anti-microbial condoms are about to be launched in Australia, and, though discovered there, the key gel ingredient was “scaled up” at Ferrier in a large project led by Rendle so that kilograms of the stuff could be made, rather than just a few grams.

Even more exciting is the news that Ferrier’s internationally renowned chemists, in collaboration with a New York researcher, made a molecule – known as compound BCX4430 – that the American National Institutes of Health has just announced shows promise in treating Ebola.

The son of a chemistry teacher, Rendle says he always had a bent towards maths and science – English was his poorest subject, although an inspiring teacher in his final year helped him improve enough to take the dux prize.

“I wasn’t aware I was even in the running – it hadn’t occurred to me. A few weeks before they were announced, one of my classmates came and sat down beside me in the library and said, ‘Who do you think is going to be dux, me or you?’ I looked at him blankly.” The colleague, who was strong in the arts, was proxime accessit.

Rendle says he’s never thought of the title as particularly important – he gained direct entry into second-year chemistry at university because of his marks in the subject, not any honour. His parents, of course, were chuffed, and all the grandparents came to Christchurch for the prize-giving.

Like Cutfield, Rendle always wanted to return to New Zealand after a post-doctoral period in England, although he says on pay rates alone and how scientists are treated here, “I can see why people don’t want to.”

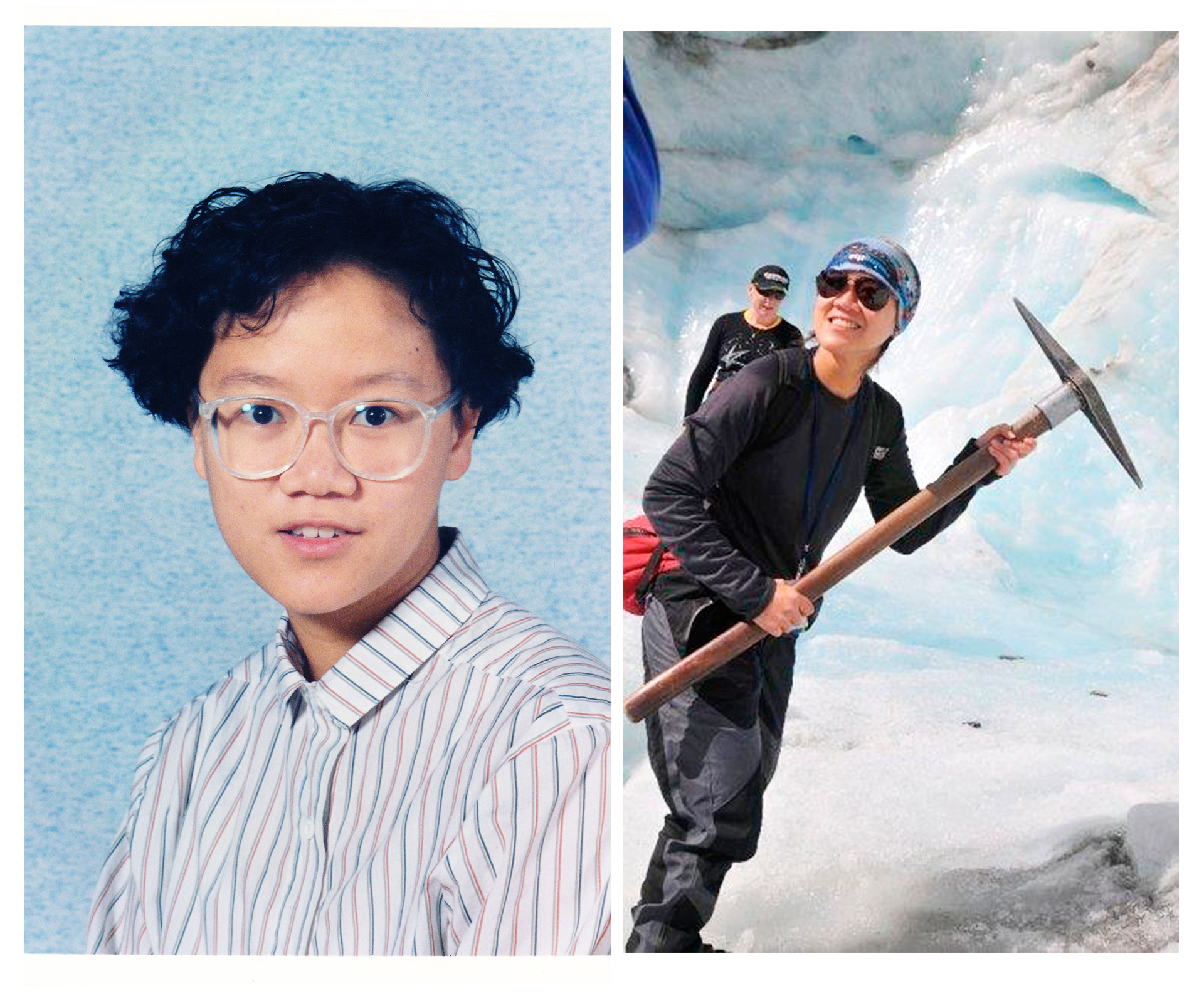

Deanna Wong as a third-former at Samuel Marsden Collegiate left, and on a New Zealand holiday in 2009.

Deanna Wong

SAMUEL MARSDEN COLLEGIATE

Class of 1992

One of the many duxes who have made their names overseas and are likely to stay there for a good while yet is Samuel Marsden Collegiate’s 1992 joint dux, Deanna Wong.

New Zealand born, Wong was raised in Hong Kong before her parents, who stayed overseas, sent her to board in Wellington at the age of 14.

Excelling at maths and chemistry, she says she always worked hard at school.

“I didn’t work hard to be dux, I was working hard to get into the universities and the subjects I wanted. When it was announced, I held my breath a little and was a little disappointed when [the other student] got it as well. It was important to me in a way.”

Wong was accepted into both Auckland and Otago medical schools. “To be honest, I was pretty sure I wanted to be a lawyer, but to satisfy my curiosity, and my parents – if you get into medical school it’s a bit of a waste not to do it – I gave it a go for a year. I didn’t hate it but decided I’d rather do what I’ve done.”

Wong got an LLB and BSc at Victoria – her science degree was a double major in molecular biology and genetics – before heading to Australia to become a management consultant. “I had job offers in law in New Zealand but the Melbourne job was quite a lucrative offer – substantially more than a first-year law graduate would get paid in New Zealand.”

Deanna Wong with her family at the school in 1990 left, and with husband Alex.

Now a partner in a Beijing law firm, and specialising in intellectual property law where she can also use her scientific expertise, Wong, 40, says that “at some stage” a return to New Zealand is likely, but she doesn’t know when. Her husband of seven years is also from Wellington, but they met in Hong Kong.

She agrees it’s a shame New Zealand loses many of its brightest academic stars overseas. “But you hope they still regard New Zealand as home and you hope a lot of them will come back for family ties.”

While being dux was an honour, she says it hasn’t helped her career. “Not many people outside New Zealand know the meaning of the word. In the States, it’s valedictorian.”

Her goal in life now, she says, is simply to be happy. “My biggest achievement is marrying my husband.”

Words by: Donna Chisholm

Photos: Alan Dove, Ken Downie and Mike White