Growing up in Te Aroha in the 80s was a kids’ idyll. We biked all over town, unfettered by stranger-danger warnings and road-safety instructions; we built huts in the bush and swam in waterholes without fear of drowning. We caught frogs in the Te Aroha Domain and played pick-up games of rugby league, ripping up the pristine croquet turf.

Weekly treats were Friday-night shopping and fish and chips for dinner; one of the annual highlights for me and my mates was the Brick Street Derby, when we raced our carts down the town’s steepest street into several tonnes of sand deposited at the finish line, just shy of the main road.

I don’t recall any of my friends’ parents being unemployed, or anyone missing a school trip because they couldn’t afford the fees. When our town bridge needed a spruce-up, half of Te Aroha turned up on a Saturday morning, paintbrushes in hand, to give the old girl a new coat.

The bubble burst for Te Aroha in the late 1980s when the Bendon factory closed, leaving 98 locals jobless. The five-storeyed headquarters of the Thames Valley Electric Power Board (the only building in Te Aroha with an elevator) was another major employer to follow suit. Then the Hauraki Catchment Board, where my father worked – later to become Environment Waikato – downsized dramatically.

Steve Hale and his daughter, Ella.

But since those industries and the workers who depended on them left town, Te Aroha’s population has been steady, a creep upwards from 3830 at the 1991 census to around 4000 today.

The town has had a few false starts over the years. After gold was discovered by Hone Werahiko in 1880, the population of the nearby Waiorongomai Valley soared from near-nothing to 2000 residents within three years. The gold rush was relatively short-lived, however, and by 1900 only a few hundred prospectors remained. Buildings from Waiorongomai were put on rollers and pulled by bullock teams back to Te Aroha. Many of the native-timber mine managers’ cottages remain in the town, as do listed heritage buildings like the Grand Tavern and Cadman Bath House.

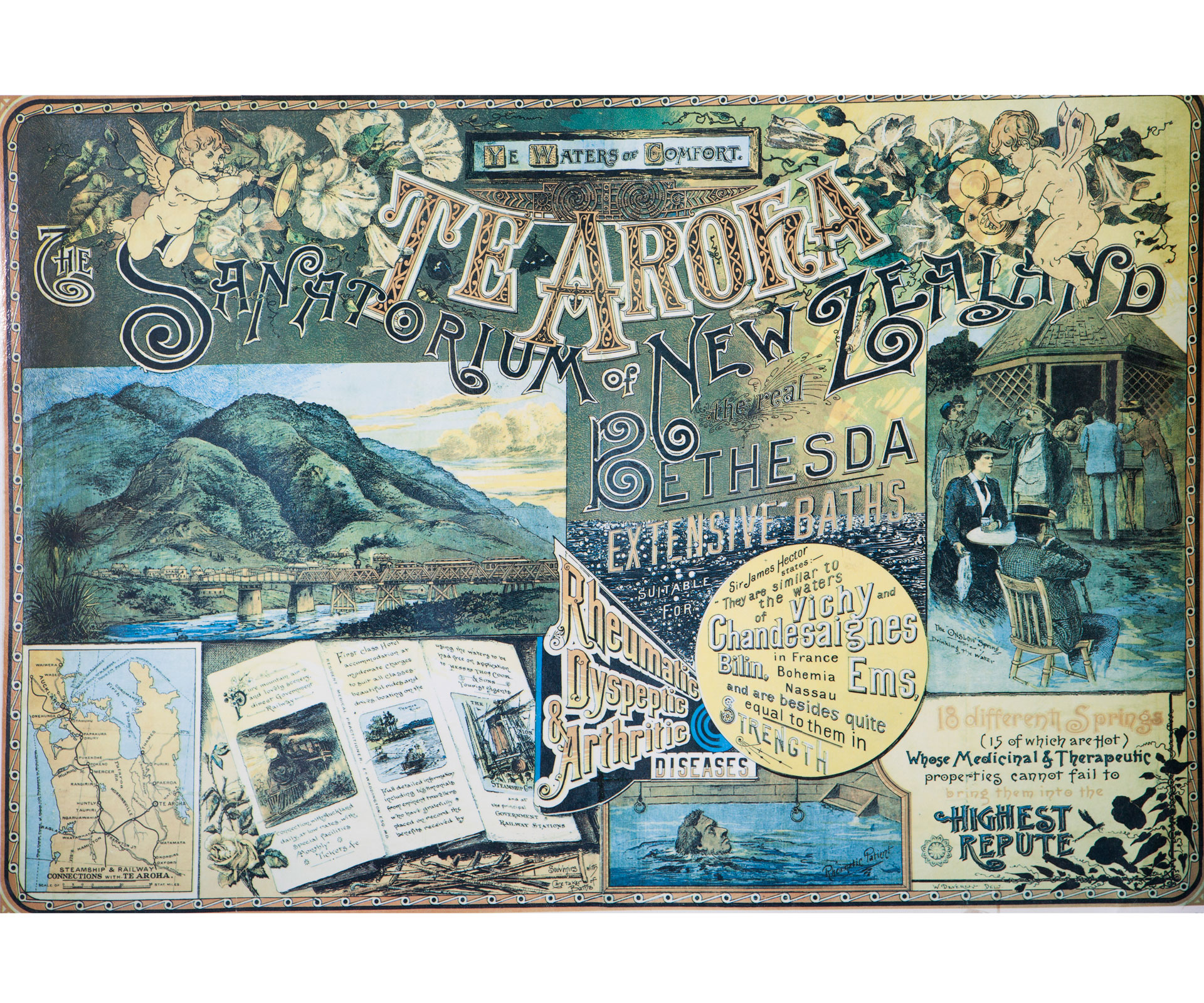

The therapeutic benefits of “taking the waters” at Te Aroha’s mineral springs drew cure-seekers from the mid-1880s to the early 1900s. For a few heady years, the government-owned bath houses drew more visitors than Rotorua or Hanmer Springs. The spa’s glory days ended when the railway from Auckland to Rotorua opened in 1894.

In my late teens, Te Aroha stopped being my centre of the universe. It was the bobby-calf season of 1993. My days consisted of 5am starts, working outside on a cold concrete pad while hooking and hoisting the hindquarters of decomposing animals onto a rusting conveyor belt. It was time to leave; to get a tertiary qualification and see the world.

In 2005, while living in Guernsey in the Channel Islands, I received a call from my father about an unexpected family illness. Within three months, my wife, Joss, son Boston and I were back in Te Aroha. It wasn’t part of my life plan. I’d been content, teaching and exploring Europe during our summer holidays. But to my surprise, the Te Aroha I returned to felt invigorating. I managed to patch together a living as a school caretaker, marriage celebrant and radio rugby host; also teaching part-time and freelance writing.

And although sausages smothered in sauce and onions were still a sports-day staple, Te Aroha of the 2000s had a busy sushi lunch bar, an excellent Indian restaurant and skilled baristas. It also had affordable housing. In 2008, we purchased a four-bedroom, native-timber bungalow on a half-acre section for $300,000.

My neighbour is one who typifies semi-retirees looking to free up capital and escape big-city stresses. He moved to Te Aroha eight years ago from Auckland, where he still owns and leases warehouses. He now works as a volunteer groundskeeper at the Te Aroha racecourse, enjoys a pint at the RSA and has joined the gun club. He doesn’t miss Auckland, but says he’s close enough to pop up for business.

A barista at Banco cafe. For Hale, the positives of living in the small Waikato town far outweigh any negatives. “The sense of community is strong.”

Jacqui Revell, who co-owns the local Harcourts agency, says it’s not just Aucklanders who are discovering Te Aroha: “We’ve recently sold properties to families from Tauranga, Hamilton and Gisborne. Some already knew about Te Aroha through family connections, some simply stumble across the place. Everyone seems to be fixated by the mountain [952m Mt Te Aroha]. We get lots of comments on how beautiful it is.”

Migrants have come from further afield, too. Two of our GPs and a school principal are South African. We have Uruguayan students, a Scottish CrossFit gym owner who doubles as an osteopath, and a vibrant Tongan community. Many of those lost factory jobs of the 80s have been replaced: within a 14km radius of town there are five major processing plants, including Fonterra, Inghams Enterprises, Tatua Co-operative Dairy Company and Silver Fern Farms. School leavers can earn around $650 a week in the hand for entry-level positions.

Te Aroha benefits from its “location, location, location”. The town is 139km from down-town Auckland and 150km from Taupo. It’s an easy drive to Tauranga (80km), Rotorua (100km) and Coromandel (106km). I can be paddling in the surf at Waihi Beach or cheering on the Chiefs at Waikato Stadium within 45 minutes of leaving my doorstep.

Looking across the croquet greens to the Grand Tavern.

There’s a lack of regular public transport, however, and only one daily return bus service between Coromandel and Hamilton that passes through town. And the downside of that 45-minute run to the Hamilton malls is a scattering of empty shops along Te Aroha’s main street. Arguably, though, local businesses that refuse to trade on weekends are missing out on the business flowing into town since the Hauraki Rail Trail cycleway was completed in 2012.

My most common local purchases include diesel, Guinness, espresso and Sharpie pens; big grocery shops we tend to do in Hamilton, where prices are considerably lower. However, living on the edge of good hunting-shooting territory has its advantages. My freezer is chock-full of home-kill bacon, beef, lamb and wild pork.

Due to my long offshore sabbatical, I probably have another 15 years or so on probation before my local citizenship status is restored. But the key for newcomers wanting to fit in is to get involved in local activities, to be prepared to help out. In my experience, the positives of living in Te Aroha far outweigh any negatives. The sense of community is strong.

The domain, where Hale caught frogs as a child.

Small towns do things differently. The recent funeral of “Mountain Radio” hardware-store DJ Wayne Pitts was held at the Cobras (College Old Boys Rugby & Sports) Rugby Club, and was attended by hundreds of locals, some in suits, others in bush-shirts and work boots. The bar remained opened throughout the service.

My children feel grounded, confident and secure in their surroundings. They attend local schools and are getting a fine education, even as some of the town’s secondary students choose to bus out of Te Aroha College’s zone to Hamilton schools.

The perception is that not much happens in small towns. My reality as a parent is there’s too much to do. My daughter packs in after-school netball training, swimming lessons, acting and dancing classes. Our winter Saturdays revolve around sport. By 9am, the local netball courts are abuzz. My daughter’s team sometimes plays two games in a row, rain, shine or gale-force wind. We then walk to Boyd Park to watch our son play rugby, often staying on to support the Cobras senior team, and enjoy a few after-match drinks.

An old poster from Te Aroha’s spa-town heyday.

I love the spirit here. The local fire siren blares at 8am, 12pm and 5pm to mark the working day. Rush hour means it may take an extra two minutes to get home.

Whenever I’m driving back towards Te Aroha and the transmitter tower on the mountain appears on my horizon, I subconsciously relax. It’s like a lighthouse guiding me back. I’m proud, once more, to call Te Aroha home.

Words by: Steve Hale

Photos by: Ken Downie

.jpg)

.jpg)