The teenage deck boy peeked out from under the protective canopy as his rubber life raft drifted at the mercy of the towering seas.

“Are we all right?” asked the frightened women sitting alongside the 17-year-old, the stench of vomit overpowering the confined space.

Toby Gray thought he had already faced the worst in a day that saw the junior crew member, just his second week on the Wahine, in charge of a raft packed with survivors fleeing the stricken ferry sinking at the entrance to Wellington Harbour.

“I poked my head out and all I could see were rocks,” says the former Lower Hutt seafarer, who is telling his story about our worst maritime tragedy in modern history for the first time.

“I didn’t say anything. I thought if the women were all right – I might have to swim for it, but they weren’t. All the people were battered, some had even turned blue, and the giant swell meant everyone was spewing up.”

Then out of nowhere an enormous wave propelled the inflatable craft over the treacherous rocky coastline on the harbour’s inhospitable eastern edge.

A couple wade along Pencarrow Coast Rd.

“The waves took us like a big surfboard over the rocks and we dropped, bumping hard on the sand,” recalls Toby. As the teenager sprung into action to get the survivors out, he now faced a fresh problem – the super-strength undertow sweeping the craft back into the harbour. With no sign of help at hand, Toby decided to put a rope from the craft over a large rock to secure it – a move that nearly cost his life.

“I knew I would have to try and get the people out but the undertow was taking it back into the water. I put a rope around a rock but it came off and got wrapped around one of my legs, then the raft got swept out on the undertow. I had run out of energy. I had a lifejacket on but all my clothes were wet. That was the worst part of the whole episode.”

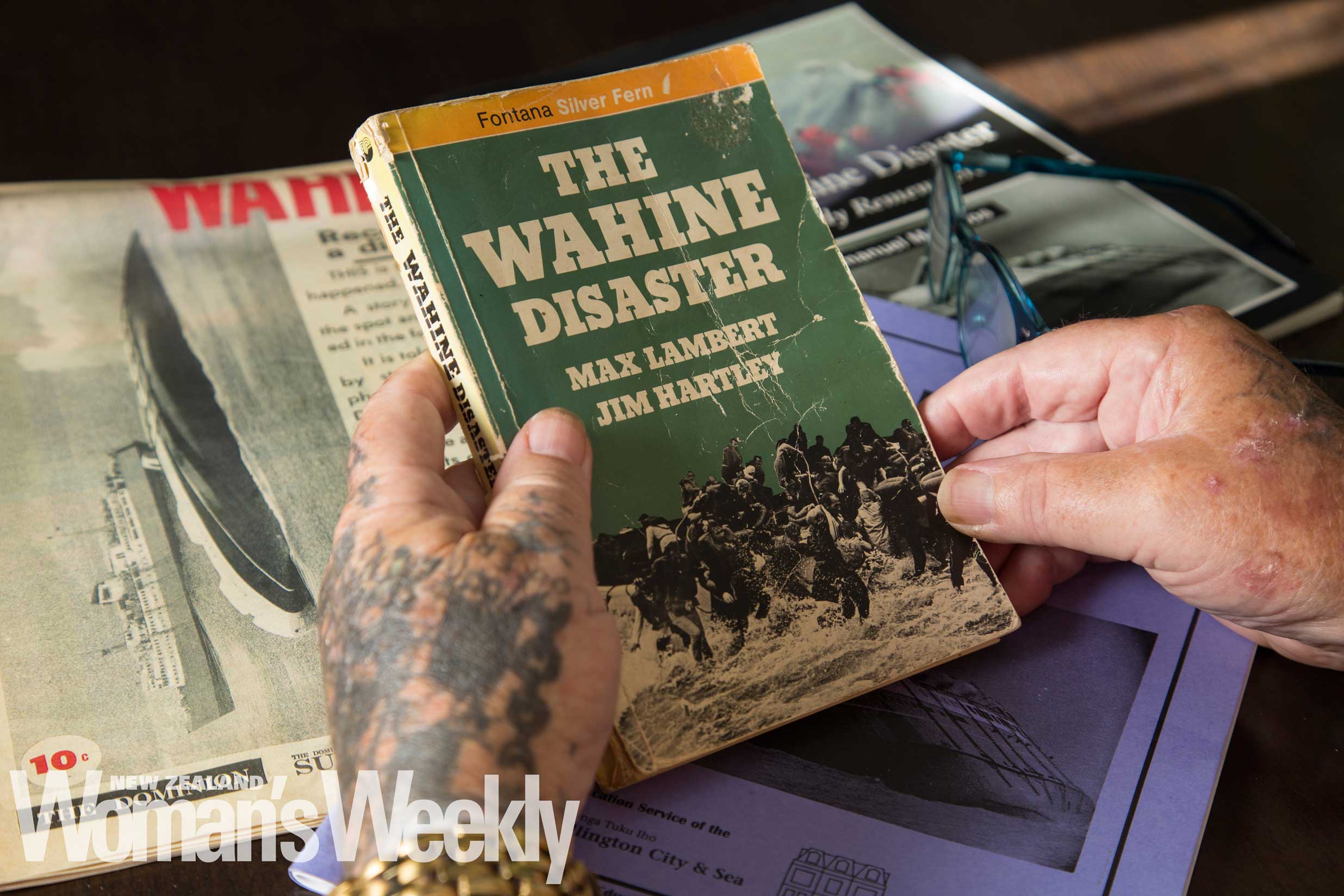

Dragged back into the churning sea, with waves smashing on his face, Toby’s luck turned as the first rescuers arrived in the nick of time and saved him from certain death. Toby’s spent the past 50 years letting the memory of the Wahine lie dormant, a ship’s graveyard tattoo etched on his upper arm a permanent reminder of that dreadful day.

But now, recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s, he wants to tell his story about the bravery and humanity he witnessed as the nightmare at sea unfolded.

His fateful passage was sealed a week before the Wahine set sail when he was rostered to take the place of another deckhand, a temporary posting he describes as his “worst luck ever”.

Despite being the youngest and newest crew member, he knew conditions were unusually bad when hoisting the ensign was abandoned as the ferry neared the harbour entrance.

“I was used to a rough sea, but I knew something was up. You could hear the pots and pans getting rattled.”

Exhausted survivors.

Then suddenly there was a smash as the Wahine veered onto Barrett Reef.

“When it went on the reef, it was like a can opener. There was a big wave that rushed over when we hit and then all hell broke loose.”

As the fierce storm lashed the stricken vessel, Toby was ordered to go down to secure vehicles in the ship’s hold, but what he saw had him fearing for his life.

“It was mayhem in the hold. Big trucks were smashing over and tipped on to their side. That’s when I knew I was in trouble.”

He awaited orders but, like most on board that day, didn’t think he was in grave danger.

“Everyone thought it was being safely towed – including me,” recalls Toby.

Passengers were in good spirits, singing and listening to radio bulletins detailing the ferocious storm lashing the capital and the rescue effort to bring the Wahine into the harbour. But the joyful strains were suddenly replaced by terrified shrieks when the large steel rope attempting to pull the ship to safety suddenly snapped, causing the vessel to list violently.

Toby says when an order was given to evacuate the ship, pandemonium ensued.

“There was screaming and yelling,” he remembers. “People were sliding down and getting hurt.”

Worse, a number of terrified passengers plunged into the sea only to lose their lives.

“People didn’t put their lifejackets on properly and a lot of people panicked, jumped into the water, and then their jackets came off. So many things happened at that time,” he recalls.

Stationed to a raft, Toby was one of the last to be lowered from the foundering passenger ferry with around 15 women and children. After clambering and jumping into their only means of escape, they floated in mountainous seas for an hour, steered by wind and tide.

“We were at the mercy of the elements,” he tells. “There was nothing I could do.”

When the raft finally ended up on a beach, Toby dared to breathe a sigh of relief, thinking his ordeal was coming to an end. But as people tried to make their escape, the stormy sea and strong under-tow posed a dangerous new hurdle to overcome.

He believes the near-perfect timing of the land-based rescue team meant the death toll wasn’t higher.

“They got everyone to shore. If it wasn’t for them, a whole lot of us wouldn’t be here today.”

Those helped to safety were taken to the Eastbourne RSA before going by bus to the city’s railway station, where Wahine victims assembled in the cafeteria. Toby finally turned up to his Wellington home, where he lived with his brother, at 7.30pm. “They were rapt,” he says of the moment he stepped through the door. “They all thought I was missing and then I turned up in a taxi!”

Toby, who encountered a second terrifying storm off the West Coast just a month later, decided to ditch his maritime career and ended up with his own painting business.

It’s taken half a century for him to go back to the coastline where 49 of the 53 victims washed up and where he narrowly cheated death. But earlier this year, encouraged by his family, he finally made his peace, visiting the Eastbourne memorial and posing for photos by the ill-fated vessel’s mast.

He says despite the day’s horrors, which he vividly recollects, the best of humanity shone through the darkness.

“People were helping people in a worse situation than they were in,” he reflects.

“You would see little kids slipping off and you would put out your hand.

“I was frightened but so busy helping people that you didn’t have time to think. I was so proud to be on there.”