The first thing I notice as Georgina Beyer welcomes me into her housing corp apartment in Wellington is a photo of her with the Queen.

Her Majesty, I think to myself, looks happier than she normally does at such occasions, a broad smile on her face that reaches her eyes. There’s a delight there and it’s easy to see why. I expect she’s thinking, ‘Here, at last, is someone who is not afraid to be herself, who won’t put on airs and graces, someone who will be interesting to talk to.’

She wouldn’t be disappointed.

Georgina, or Georgie as her mates call her, is a people magnet. She is warm, sensitive, engaging and often outrageous. She is also a great raconteur.

As we sit to begin our chat, I spot another picture of Georgina with the Queen.

“Oh that was in ’95 on my first trip to Government House in Wellington.”

She was the mayor of Carterton at the time.

“Dame Cath [Tizard] was a great supporter of mine, and she brought the Queen over to meet me.” Again I notice the big, real, smile from Her Majesty. The two chatted and then Georgina made her way to the VIP tent where she met Joan Bolger, the wife of then Prime Minister Jim Bolger.

“Joan said to me, ‘I see you met the Queen,’ and I said, ‘She’s the first real Queen I’ve ever met!’”

She laughs uproariously at this. Because of course she is loud and proud as a member of the transgender community.

Needless to say, the headline in the British papers the following day screamed: “The first real Queen I’ve ever met, by George”.

Georgina was born George in November of 1957 to Noeline and Jack Bertrand. Noeline, of Te Ati Awa heritage, was training as a nurse. Jack, of Ngati Mutunga, was a policeman. The couple eventually divorced and son George was sent to live with Noeline’s parents on their Taranaki farm, where he stayed until his mother remarried.

It wasn’t ideal. Little George’s grandfather didn’t want his grandson around.

“One day my uncles had been out hunting and they brought back a little fawn as a pet for me. I was delighted. But I let it run riot and it got into the garden. My grandfather dragged me out of bed one morning, then he killed the fawn in front of me and thrashed me with a piece of bamboo.”

Georgina is matter-of-fact as she tells me about this.

“Times were different then,” she explains. “It was just the way things were.”

“My grandmother was my greatest protector.”

Georgina was just 10 when her grandmother died. She was devastated.

Like many Maori children of the time, Georgina was, in her words, ‘pakeha-fied’. Te Reo was foreign to her.

“I remember going to stay with my great aunt in the school holidays. She had a moko. I was frightened by it. When I had to attend a tangi, or funeral, I was terrified by the whole marae situation.

“At three or four I began to feel different. I used to play with a little girl down the road. There was a big dress-up box and I was drawn to the dresses. We’d put on little shows and all the adults loved it. But as I grew older, about seven or eight, the adults began to condition me out of it. I was expected to go out hunting and do ‘boy’ things. I hated it. I began to relate dressing up as a girl with punishment.”

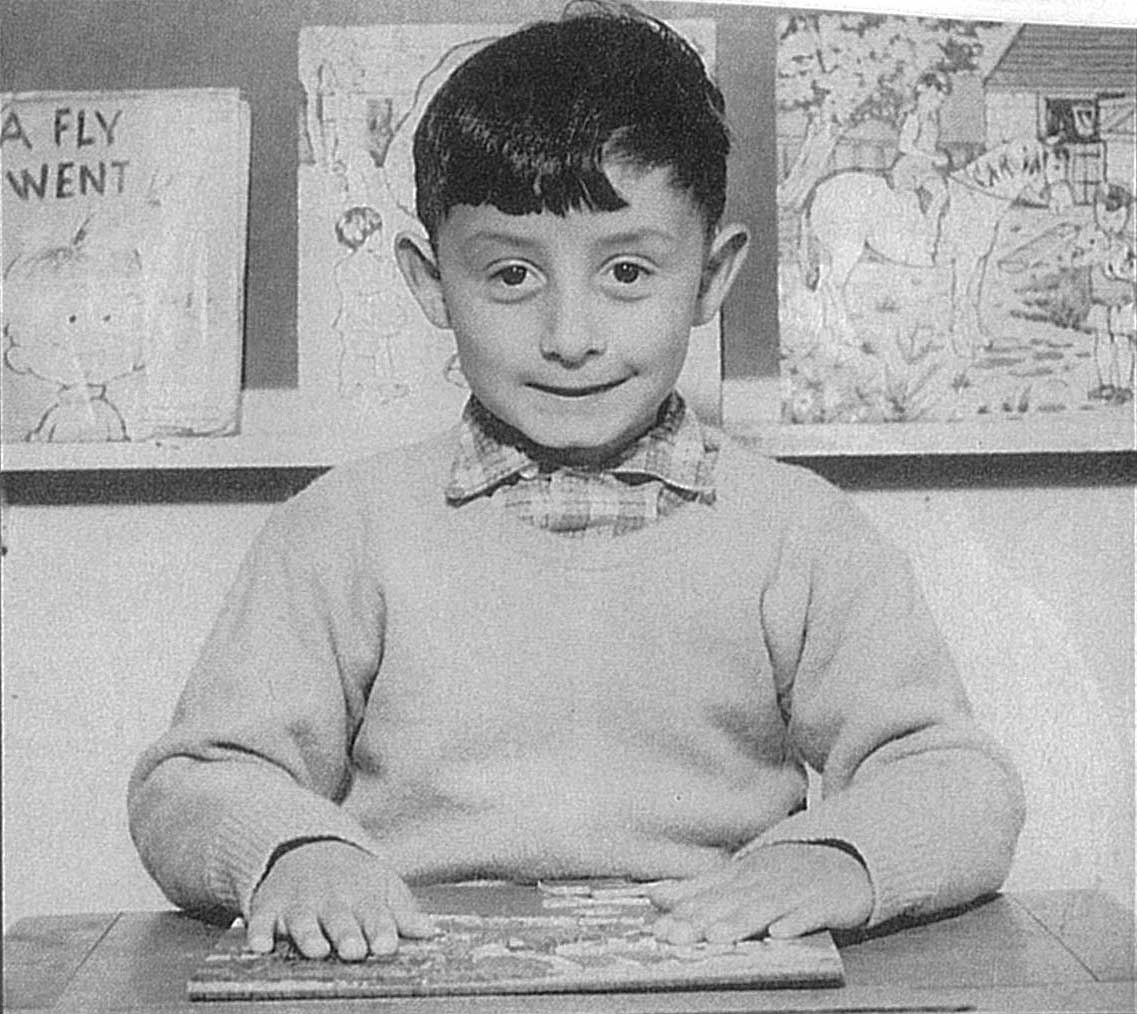

Young schoolboy George.

Georgina’s mother, Noeline, had by now remarried. Her new husband, Colin Beyer, a young Wellington lawyer, was a mover and shaker in the capital.

He and his Wellington College friends, including Ron Brierley, and Trevor Beyer, Colin’s brother, were members of the Wellington brat pack of the time.

Original directors of the property company Brierley Investments, they were all extremely wealthy by the end of the 1960s. They lived the high life.

Georgina remembers that along with fellow property developer Bob Jones, they would gather their families and have Sunday cricket matches in Otaihanga on the Kapiti Coast.

Georgina had returned to live with her newlywed mother when she was about five. She continued to want to dress as a girl.

“I became secretive about it. When Mum and Dad were out I would dive into Mum’s lace tablecloths and prance about in them. Then I would replace them in exactly the same place.”

One day, though, she decided to wear a dress outside the house.

“Mum was a wonderful dressmaker and milliner. I dressed to the nines and then trotted off to the dairy. Unfortunately, the dairy owner recognised me and phoned my mother.”

Her mum and stepfather were horrified.

“I forgive them now – after all, they were the social mores of the times.”

By the time George reached intermediate school, Noeline and Colin’s marriage was in trouble. Their son was sent to the exclusive Wellesley boarding school in Day’s Bay. They were happy years.

When Georgina was a member of parliament, she returned to Wellesley for a reunion. She was assigned one of the current students as a chaperone and noticed him looking confused as he read her name tag. It said: Georgina Beyer – old boy.

“Don’t worry, she told him, “look at all these people – I’m the only member of parliament and you’ve got me.”

“I’m glad I went to Wellesley,” she tells me now. “It grounded me, the discipline there.”

By the time he left Wellesley, George’s mother’s marriage had broken down and Noeline would again be on her own. With no money for private schools, George was sent to Onslow College – another great move for him.

Georgina on the steps of parliament.

“There was a huge student protest running at the time to get rid of the uniform and short-hair rules. We staged sit-ins and forced the resignation of some of the board of governors. We were successful and became a mufti school. The ‘disobedience’ had paid off and I relished it,” Georgina laughs.

The seeds of her future activism were planted there.

Noeline then moved to Auckland, to a nursing job at Middlemore Hospital. George found himself at Papatoetoe High School and it was there he began a lifetime love affair with drama. Of course one of the attractions was that it allowed him to dress up and wear make-up.

“I became a theatre groupie.”

By 16, George had left school, against his mother’s wishes, intending to go to drama school in Wellington. But money was a problem. How to earn it? It wasn’t long before George was living as Georgina.

She was inevitably drawn to the capital’s nightclub scene and the transgender community, centred on the strip clubs and cabarets of Vivian Street. She had cut all ties with her family.

“I didn’t want to deal with their disapproval,” she admits.

She was being supported by friends in the gay community and became a regular at Carmen’s Balcony where she was entranced with the gorgeous show “girls”.

“Once they opened their mouths, I realised what they were… trannies.”

Georgina began working as a singer and cabaret performer but ended up working in strip clubs and supplementing that income on the streets. They were reckless days, the early 1980s.

“We took a cocktail of drugs – uppers, downers, hormones – enough to kill an elephant,” she says ruefully.

The glamorous woman George became as Georgina.

Eventually she decided the time was right to come out. She called her mother to tell her about her new status. Noeline was not impressed.

She had her own problems. She was dying of cervical cancer. She lost her battle in the late 1970s, at just 43 years old.

Georgina finally found enough cash to pay for her gender reassignment surgery in 1984. At last comfortable in her own skin, her life began to look up. She found work and success as an actress.

Her starring role in the seminal Kiwi drama, Jewel’s Darl (1987), earned her a best actress nomination in the film and television awards of the day. The fact she was nominated as best actress is a personal triumph she relishes to this day. Other roles followed.

But it was her move to the Wairarapa town of Carterton that would prove a defining moment in her life. She worked as a radio host, and found herself becoming involved in local politics. It was the homeless who galvanised her into action.

In 1991, after the “Mother of all Budgets”, benefits were slashed by 25 per cent and the homeless began to appear on Carterton’s streets.

Georgina wanted to park a caravan on council land to provide shelter for those people. The council turned her down. She was infuriated by this lack of concern and took little persuading to run for council, knowing she could make a difference.

Although she missed out narrowly on her first attempt, she would go on to become mayor and then, once her credibility was firmly established, the Labour MP for Wairarapa.

“I felt a great sense of achievement. But it was hard. I had to start from scratch [and learn the business of politics].”

As a competitor on television show Dancing with the Stars in 2005.

It was a lonely time. “It took a long time to gain acceptance in the role. It was two years before the mayor would invite me to his Christmas function,” she says.

As the world’s first transgender mayor and MP, she put Carterton and the Wairarapa on the map.

“I was shameless about promoting them. You can’t fritter away those opportunities. Suddenly people built up pride; there was no ‘ooh yuck’ factor.”

She left parliament in 2007 and since then has struggled with finding work. You would think she’d be snapped up – a high-profile mover and shaker with a good brain, a sharp wit and a list of achievements behind her – but it wasn’t to be.

“Former politicians are sometimes box-office poison,” she tells me sadly. “I guess Georgina Beyer has a reputation as being feisty and that’s too scary for some people.”

She had to sell her house to get money to live. Eventually the money ran out and, struggling with ill health, she was forced to apply for the dole. The humiliation still causes the tears to spill.

“The last time I’d been in that WINZ office I was the local member, escorting the prime minister. It was embarrassing, shameful. It destroyed a piece of my soul,” she sobs brokenly.

She is particularly fragile right now, recovering from a kidney transplant that she hopes will be the key to a new life.

Diagnosed with chronic kidney disease in 2013, she spent four years “of hell” on dialysis, until, on her 58th birthday, a friend offered her his kidney.

Meeting the Queen.

The drugs she still has to take are taking a toll. She has regained the 20kg she lost on dialysis, and then some, bemoaning the fact she can no longer fit the designer outfits she used to wear. And she is tormented by mood swings. But each day she’s closer to recovery.

The transgender community has much to thank her for.

“All those years selling my ass on Vivian Street, I stood on the shoulders of those who went before. Now people stand on my shoulders. There are now transgender doctors and lawyers. People can at last reach their potential.”

She has a comforting word for parents of transgender and homosexual children.

“Don’t beat yourselves up,” she says. “We tend to forget that they sometimes punish themselves for the way their children have turned out.”

Now nearly 60, Georgina is looking ahead to better years after recovering from her kidney transplant.

Georgina hasn’t given away thoughts of a return to politics. Her heart is in the Wairarapa. But she tells me, wistfully, “I’ve sacrificed my personal life [for politics], I’ve never had a husband or a boyfriend and that would be nice.”

There is a loneliness there, a space that yearns to be filled.