Despite diversions along the way, Claire Robinson – artist, academic and political scientist – eventually fulfilled what seems to have been her destiny, in a job that combines all her disparate talents.

Robinson, 53, is Pro-Vice Chancellor of Massey University’s College of Creative Arts in Wellington, where she oversees 150 staff and 1600 students. She’s also an occasional political commentator on TVNZ’s weekly Q+A.

Her parents, Alan and Marijke, were huge influences on her life and eventual career direction. Alan, a political scientist, died when Claire, his eldest child, was just 13, and Marijke Robinson, a public servant and political activist, died last year.

Robinson’s domain at Massey University is a minimalist, industrial-chic open-plan space dominated by a long communal kitchen with heavy-duty coffee machine and barista. Only Robinson has her own office, and although its glass walls ensure the integrity of the overall concept is maintained, inside it’s a riot of colour.

What are you wearing and what’s behind the flamboyant office design?

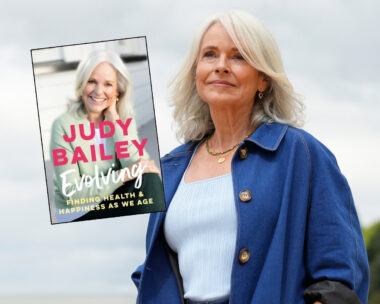

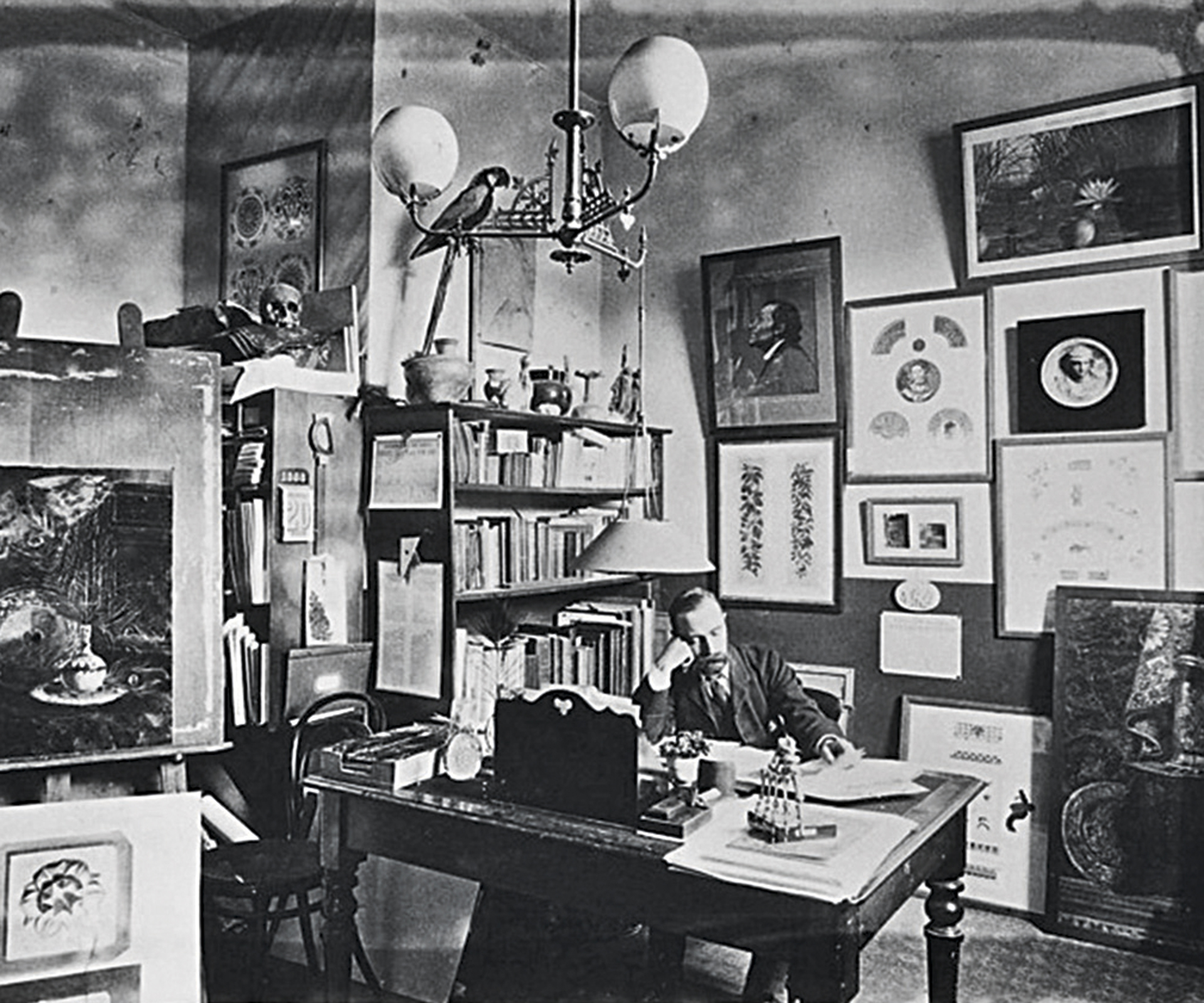

This dress is up-cycled and made from old New Zealand Post uniforms. It was designed by one of our students as part of a project called Space Between, which looks at how design can find solutions for clothing and textile waste. When I took the job in 2012, I decided to put my stamp on my office. One of my best friends works for me and she is phenomenally talented in terms of interior decorating. She went off and collected colours and fabrics; she also made the crazy lamp with the parrot. Arthur Riley created the school in 1886 and we have a fabulous black and white photo of him sitting at his desk with a skull. He also has a parrot sitting on his bookshelf, so that is a nod to him. A lot of office design is very masculine – brown, grey, white – and I wanted to feminise the work space, so that’s why I was keen on lots of florals, patterns and colours.

Tell me about your circuitous path to this role, especially your mother’s influence.

Mum was Dutch and came to New Zealand in 1960 after falling in love with my father when he was doing his PhD in politics in The Hague. Dad worked for Victoria University as a political scientist and Mum was in Karori raising three children. She had been a very cosmopolitan young Dutch woman, and arriving in Wellington in the early 1960s was a shock. She couldn’t find coffee and found everything very provincial, so she went through a period of misery raising us. In 1970, she went to hear Germaine Greer speak at Victoria University and it was a transformative moment for her.

Claire Robinson: “We grew up in a whirlwind of political activism.”

What do you remember of your mother’s political awakening?

We grew up in a whirlwind of political activism, following behind Mum at every protest march going in the 70s. Mum started the Women’s Electoral Lobby in 1975 with Judy Zavos – she’d gone through the madness of suburban neurosis, then came out the other end a feminist. She had also done her master’s degree at the same time, looking at the educational aspirations of kids at Naenae College and Onslow College and whether books had had an influence on their success at school. She surveyed these kids to see how many books were in their homes and what sort of books. It is no surprise to us now, but it was quite ground-breaking research at the time. It showed the more books you had in your house, the more likely your kids were to succeed at school.

You grew up surrounded by books?

We had political-science books all over the house, and encyclopaedias. Dad would sit with us at night and look through non-fiction books and he would collect series, as we did in the 1970s – The History of the World and all the Time Life books.

Mum’s original degree was in English and she had books from the 1950s and 60s. When she died and we were clearing out her house, I found this amazing European edition Penguin series that I couldn’t bear to throw away. The covers alone are so beautiful; they are awesome artefacts.

School of Design founder Arthur Riley.

How important is that creative side?

My mother was a great sewer, a knitter, and did crochet – she was always making things and that was a really strong part of me. I loved art, so I had that side, then my mother’s feminist-activist side and my father’s political work. I grew up with elections, and politics was part of my life. It was just there – Mum fighting with [Robert] Muldoon in the 70s, and in those days my father was a political scientist and did lots of commentary in the newspapers.

You went to university at 16 and graduated with a BA at 19. Then you travelled, worked at the State Services Commission and joined Foreign Affairs. How was your time as a diplomat?

I went to Kiribati on a joint posting with my then husband Brett Lineham, and that was quite unusual. Kiribati was a hardship post then, and still is. We opened the post and were the first full-time diplomats. Kiribati was a very difficult place to live.

Claire with father, Alan, and younger sister Kate in 1968;

When you returned, you worked for a year as Women’s Affairs private secretary in Jenny Shipley’s office, then went to design school, and had two children while continuing your studies. What direction did you take?

I retrained and got a Bachelor of Design, majoring in visual communications design. My major thesis project was on how to engage young people with the MMP referendum process. After the “mother of all budgets” in 1991, I developed an interest in how political messages are sold. I later put all those interests together and did my PhD in political advertising and political marketing. Then in 2002, Maryanne Ahern [now executive producer of Q+A] trotted into the office to ask a colleague what they thought of Jim Anderton’s Progressive Party’s new logo. I said to her, “I am doing my PhD in this area, so if you want any comment, give me a call.” That was that. Since then, there has been this other side of me that is doing political commentary.

Do you have much time for reading?

I read all through the day, when I’m not meeting or talking with people. Emails, texts, Twitter, policy papers, budget documents, academic books and articles, and online news about politics, education and design. I only get time to read as a leisure activity over the summer holidays. Last summer I read [Eleanor Catton’s] The Luminaries – actually, it took me two summers to get through it. I went on to The Goldfinch [by Donna Tartt], which started well, but I couldn’t finish it because it was too full of angst, then on to David Baldacci’s The Escape. I have books beside the bed: Swedish murder mystery Buried Angels by Camilla Lackberg, and the more serious Why the West Rules – for Now, about the rise of China, by Ian Morris – but I can’t read more than two pages at night before falling asleep. My current research project is on visual bias in newspapers in election years, and that is the stuff I can sit and think about and get lost in. Hours can just go by. I love what it does in my brain, the way it completely pushes me into spaces I know nobody else in the world has been. That is the great thing about doing academic research – it is completely original.

*Words by: Clare de Lore

Photos by: Hagen Hopkins*