Not many people have a full-sized moa skeleton in the front room, but then Christine Fernyhough is not most people.

Her home is full of surprises. There she stands, a female stout-legged moa, smaller than the giant fortunately, in a big glass enclosure at one end of Christine’s vibrant turquoise-coloured Parnell living room.

Christine is a collector. For more than three decades she has been haunting second-hand shops and auction houses the length of the country in an effort to preserve what she sees as a golden era in New Zealand.

The 1950s and 1960s were a time when New Zealand came into its own.

A simple, uncomplicated time when we made things ourselves, before manufacturing was outsourced to China.

Her collection includes furniture, toys, Crown Lynn china and a vast array of Kiwiana. Much of it is displayed in the old family bach she bought with her husband John Fernyhough at Mangawhai, north of Auckland.

They called the bach The Butterfly House and, yes, as befits its mid-century origins, there is a splendid butterfly on the wall near the front door.

Now she’s published a book of the same name to immortalise the collection and the bach.

It’s a delightful, visual, nostalgia fest. Entertainingly written by Chrissie and with vibrant photos, it is both a memoir of seaside family life and a vivid account of our social and cultural history.

“I didn’t start out to make a collection, the collection made me,” she explains.

It is also a revealing study of the spontaneous, passionate woman who wrote it.

The Butterfly House is full of collectables:

Christine is the second of three children.

They grew up on the classic Kiwi quarter-acre section. Theirs was a happy childhood, full of people and fun.

“We had lots of pot luck dinners and Uncle Jim would play Tiptoe Through the Tulips on the piano.”

She remembers her parents as hard-working, honest and strong on family.

“Dad was one of six, so there were lots of uncles and aunts and cousins. My father’s sister was the best baker. There was always a trolley full of cakes at her house – sponges and condensed milk slices.”

Christmases were generally spent on her aunt and uncle’s orchard in Huapai.

“One year they came to us in their green flat-deck Bedford. There on the truck was a beautiful burgundy bike for me. I called her Saucy Jane, and I rode her for years.”

Her memories will resonate with so many of us who grew up in New Zealand in the middle of last century.

Her parents, Angus and Gladys Don, scrimped and saved to send her to Diocesan, one of Auckland’s leading private schools for girls.

“I was good at learning and I had a great group of friends.”

A naturally gregarious person, Chrissie remains close to many of those friends and still sees them regularly.

“I draw great strength from my Dio friends.”

Like many women of her generation, she headed off to secretarial college after school.

“Dad thought uni was a stopgap before marriage,” she smiles ruefully.

Now, well into her 70s, she’s working her way towards a BA in art history.

She married and had her three children young – David, Kate and Joe were born by the time she was 26.

But it was her second husband who remains the love of her life. She met John Fernyhough at an art group and they became inseparable.

“He was my greatest mentor. He had a wonderful facility for peeling the layers off the onion… an eclectic and lateral thinker.”

John was one of the most influential businessmen of the 80s and 90s, one of the brains behind the state-owned enterprise model and the first chairman of Electricorp.

They moved in powerful circles, counting among their friends other multi-millionaire captains of industry like Doug Myers, Alan Gibbs and Charles Bidwill.

It was those corporate contacts that Chrissie would call on for support when she co-founded the Duffy Books in Homes programme with Once Were Warriors author Alan Duff.

The charity, which began in Auckland and Northland in 1994, now brings books to otherwise bookless homes nationwide.

Her programme to help gifted children from low decile schools grew out of Books in Homes.

“All New Zealand’s resources were directed towards at-risk children. We tend to forget about that 10 per cent of the population that’s gifted. We were in danger of losing a lot of gorgeous creativity and lateral thinking. These kids are the leaders of the future and I’m afraid they still don’t get a fair go.”

The programme was eventually abandoned because it was considered elitist.

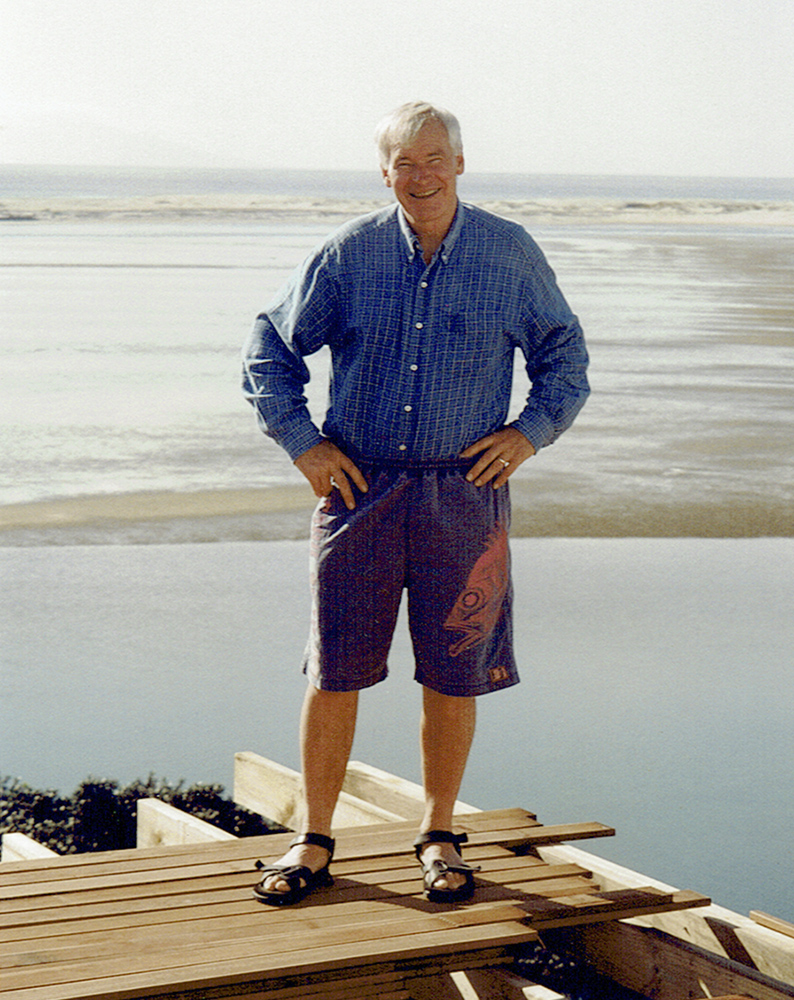

Chrissie’s late husband John Fernyhough during bach renovations.

Chrissie is committed to improving the lot of the nation’s youth, particularly those from troubled backgrounds.

She is a patron of the Limited Service Volunteers programme at Burnham Military Camp for unemployed youth.

“It’s a job-ready programme, I don’t call it boot camp. They are universally keen on boundaries and structure. There are remarkable officers running it and remarkable young people taking part. They learn self-respect, responsibility for others, and self-responsibility.”

The success rate is high. At the end of the course 80 per cent get jobs and after three months 70 per cent are still employed.

Christine has written a typically pithy and humorous handbook to augment the course, Rockhopper’s Tips for Getting Ahead and Getting a Job.

It’s illustrated with quirky graphics of rockhopper penguins. Typical snippets: “Rockhoppers stand tall and look you in the eye”and “they wear black tuxedos over clean white shirts.” Simple messages delivered in a delightfully non-preachy way.

Of her philanthropy she says, “I’m lucky enough to have financial support. I think it behoves all of us to give either time or money or both to people.”

Time is something she didn’t get enough of with her beloved husband John.

They enjoyed 20 years together and then cancer claimed him at just 65.

In one of those dreadful twists of fate she lost the two men who meant most to her within hours of each other.

Funerals for her dad, Angus, and for John were held just two days apart. The devastation was profound.

But she eventually found the courage to rebuild her life.

“I thought it was time to get out of eating chops and drinking chardonnay. I went to visit my close friends Dick and Jude Frizzell in Hawke’s Bay. I was surrounded by fat contented animals and a cornucopia of fruit and grapes… and I thought, ‘I’ll go farming.'”

It was a typically spontaneous thing to do.

Chrissie had never farmed before – she was a city slicker from a privileged background. And it wasn’t just any farm she chose.

She bought the South Island’s iconic high-country station, Castle Hill, having spent less than 24 hours roaming its craggy peaks and tussock flats.

“I was enthralled by its beauty,” she tells me simply. Her love affair with Castle Hill lasted 10 years before – missing family, her children and nine grandchildren – she was drawn back to Auckland.

In that time, she and her team turned the rundown station around.

The locals were waiting for her to fail, but instead they came to admire the energetic woman who learned to ride and muster on horseback and dag and drench her own sheep.

It wasn’t easy. She reckons she survived those lonely early days on a diet of Bob Marley and scotch.

She turned her experiences into a bestseller, The Road to Castle Hill: A High Country Love Story, published in 2013.

Chrissie would leave Castle Hill sporting a permanent limp after getting caught between an angry cow and her calf. Her leg was broken in three places and her ankle crushed.

She was alone at the time and had to crawl to her truck and drive herself back to the homestead to get help, with the agony of opening and closing multiple gates on the way.

Chrissie impressed the locals with her tenacity during a decade farming at Castle Hill.

Despite that, she is now in the throes of setting up a new farm, near her Mangawhai bach.

It’s a more manageable nine hectares this time, totara-covered and overlooking the Brynderwyns.

She’ll run a flock of Beltex sheep there, bred in Belgium for their “big bottoms”, she tells me. “Extra meaty!”

The new farm and her family are now her top priority.

“They say you can take the person from the farm but you can’t take the farming out of a person. I love space and air and animals. And I really like sheep and border collies.”

Chrissie is now passing her love of adventure to her grandchildren. “I want them to have done things.”

She took two grandsons to Tuva in south Siberia, considered the throat-singing capital of the world.

The nomadic Tuva people developed throat singing as a way to muster stock. The sound is always associated with nature, wind, water, leaves and the hooves of horses.

Chrissie brought the top throat singer to New Zealand last year for a sold-out tour.

“We have so much to learn from these people. They listen to the music of nature, of life. We’re inclined to think they’re primitive but they’re more in tune with what the world’s about than most people.”

She’s taken other grandchildren to Antarctica and the Galapagos.

I bet they loved her company – life with Chrissie is an experience to be relished.