He was a big man – surely far too big for his own good. And when he walked through the door of Auckland University’s Human Nutrition Unit, Professor Sally Poppitt would have laid odds on him being well on the way to diabetes, as most people his size are.

He ticked all the boxes to be high risk. Obese, sedentary and with a diet high on junk food, he, like many other New Zealanders of similar dimensions, looked like a diagnosis waiting to happen. Alongside him in the waiting room, the slightly-built Indian man was dwarfed. Yes, he was overweight – most of those seen here are – but only slightly, the evidence a tight, round belly bulging over his belt buckle.

If Poppitt needed any more evidence that looks can deceive, it was this pair: the smaller man was on the verge of diabetes, the bigger man was not. Though he may have had other health issues because of his weight, diabetes wasn’t one of them. And it was no aberration. Scientists know that people of Asian ethnicity are susceptible to diabetes at a younger age and at a lower weight than Pacific people or Europeans.

But why? In the notoriously complex field of nutrition and metabolic health, it’s one of the most baffling questions of all, but a vitally important one that has ramifications for us all as we get older and fatter.

Poppitt, the Fonterra professor of nutrition at Auckland University, heads a team of scientists looking for the answers. It is one of five key research areas that make up the High-Value Nutrition National Science Challenge, a government-funded, $83 million, 10-year programme with the ultimate aim of finding food-based solutions to some of our commonest maladies – including obesity and diabetes, gut upsets, asthma and infant malnutrition.

Controversially, however, the main aim of the investment, from the government’s point of view, is not to make us healthier, but to add $1 billion to the economy by providing the evidence to allow health claims to be made on foods or supplements that we sell already or are yet to be developed. Imagine adding a blackcurrant extract to a breakfast cereal to help prevent asthma, or a yoghurt that stops your diarrhoea – and having the evidence to prove it.

It’s blue-sky stuff, challenge director Professor David Cameron-Smith agrees, and the single largest government investment ever in food and health research. “It is fundamentally important to invest in areas that impact on people’s health and there is no more important question than what foods are good for you and how can we build an economy based on food and health. If we don’t start taking on the hard, big questions, particularly those where we know there is enormous consumer need, then the boat passes us by. This is a whole new dawn, and a whole new opportunity to get things right.”

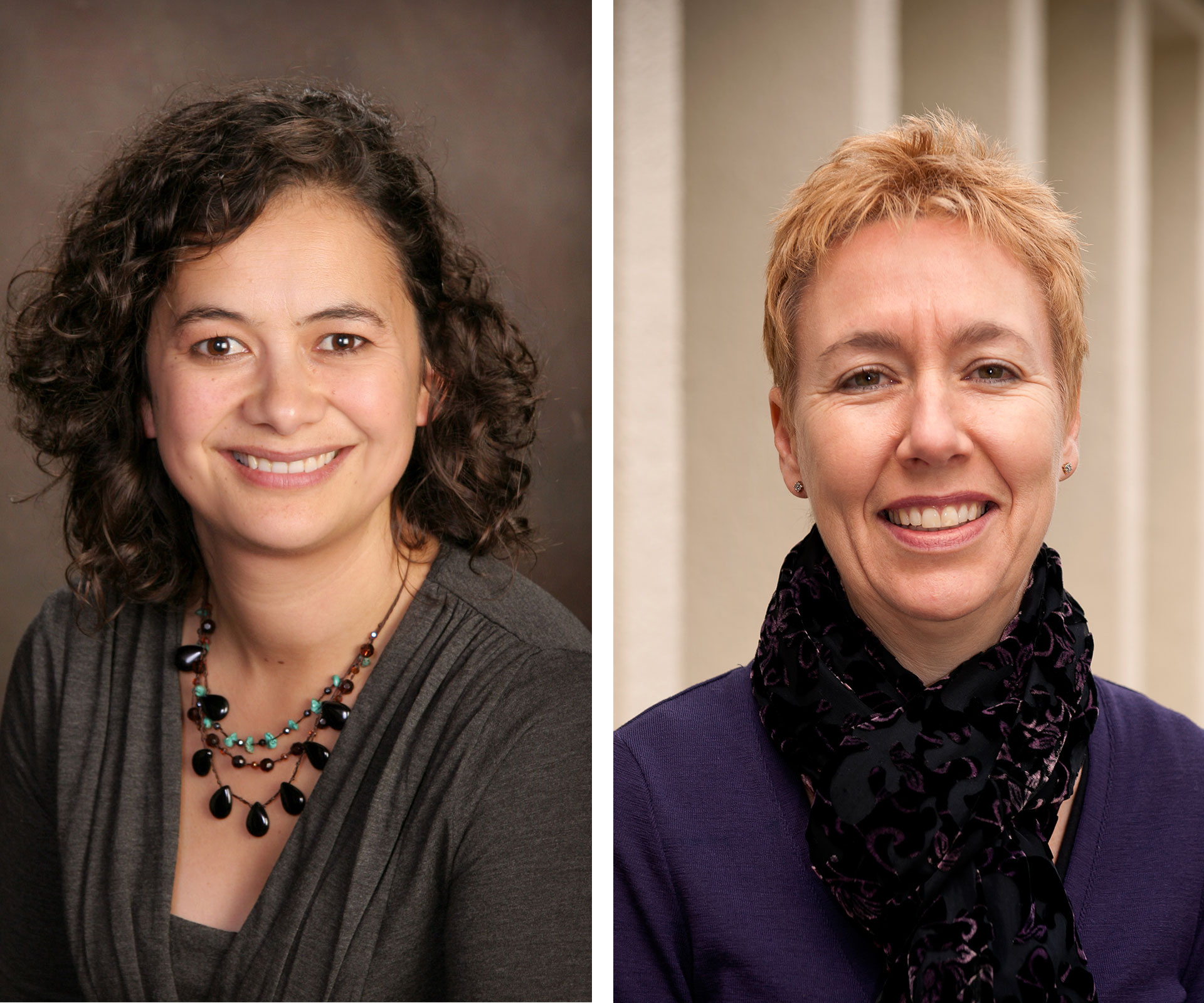

Left: University of Otago nutrition researcher Lisa Te Morenga says now even children are starting to develop fatty livers. Right: Professor Sally Poppitt and her team are investigating the “thin on the outside, fat on the inside” theory.

At the Human Nutrition Unit, Sally Poppitt sees all shapes and sizes – most of them large, or very large. What she’s learned, though, is that it’s impossible to predict from size alone who will be at increased risk of diabetes and who will not. When assessing candidates for trials at the unit, in about a quarter of cases, “I think they will definitely have a problem and they don’t, or I think they won’t and they do.”

In nutrition research, it’s called the “TOFI” theory – thin on the outside, fat on the inside – which means that even an apparently lean individual can store their body fat in the abdomen around their vital organs instead of the safer option, in the subcutaneous tissue, under the skin. It’s the visceral, rather than subcutaneous, fat that infiltrates the liver and other key organs and is associated with so-called metabolic syndrome – pre-diabetes – and type 2 diabetes.

Scientists made the connection around 30 years ago, but it’s still not well understood, meaning many of us are still reassured by a healthy BMI (body mass index) that may be completely irrelevant to our individual health risks.

In March, researchers from North Carolina’s Duke University reported that the gene Plexin D1, which is known to be involved in building blood vessels, may influence how and where we store fat. Zebrafish missing the gene had less visceral fat and were protected from insulin resistance – a precursor of diabetes – even when fed a high-fat diet. The American work has been bolstered by a Swedish study showing that Plexin D1 levels are higher in people with type 2 diabetes.

University of Otago nutrition researcher Lisa Te Morenga, who’s working with Poppitt, says around a quarter of adults have a fatty liver without knowing it, and now even children are starting to develop the condition. The best indicator of visceral fat is waist circumference – it should be half your height or less.

“I’m quite fat around my middle, but my doctor will say, ‘Don’t worry, you’re lean,’ and I say, ‘No, I’m not.’ I often worry now we are becoming so obsessed with fatness we are not seeing the wood for the trees. Perhaps we rely too heavily on obesity or overweight as a trigger to investigation when you can be just as unhealthy with a normal body weight.”

Auckland University of Technology nutrition professor Elaine Rush agrees. “I think health and food literacy are very poor in the population and probably not so strong in the medical profession, either. The focus is on how much space you take up and what your silhouette looks like, rather than functional measures like how fit you are and the quality of the food you are eating.”

At 63, she says her body fat is around 38 per cent – above what is considered healthy for her age and gender (31-36 per cent). The figure surprised her, but she’s not obsessing about it, saying she eats well, exercises regularly and is functionally fit. “I don’t get puffed when I walk up four flights of stairs and I biked the Otago rail trail in December.”

It takes specialised medical equipment to measure visceral fat – CT or MRI scans, or a machine known as a DEXA scanner, more often used to test bone density. Rush’s DEXA studies have revealed the extent of ethnic differences in body-fat ratios compared with BMI. For the same weight and height, for example, Indian women have 10 per cent more body fat than Pacific women. “It means they have less muscle and while I haven’t done the research to prove it, it’s lack of muscle that makes you more insulin resistant.”

One in six Indian women in Auckland has diabetes in pregnancy. “That’s huge. It means their babies are going to be born with more fat, so it’s a perpetuating cycle.”

One in six Indian women in Auckland has diabetes in pregnancy.

While we often think of Pacific people as being particularly prone to diabetes, the opposite is true – they are relatively protected, but develop the disease because of the sometimes vast amounts of extra weight they are carrying. Indian and Asian populations, however, tend to develop metabolic complications with lower ratios of body fat.

We might think those who seem to effortlessly stay slim are the lucky ones, but David Cameron-Smith says in evolutionary terms, those who can gain weight and hang on to it are better off. “The current environment that is creating this cataclysmic state is just a blip in a long evolutionary cycle. Wait for the next famine and the skinny people are goners.”

He says for the past 2500 years, Pacific people have been an “outstanding success”. “They’ve weathered tropical cyclones, they’ve been in environments where there are periods where food is plentiful and in absolute famine. They are remarkable survivors and it is only now, when they are living in the West, that it’s an absolute disaster.”

In the 1950s and 60s, says Cameron-Smith, the only people doctors saw with fatty liver disease were alcoholics. Now, at least half those with fatty livers haven’t been on the turps, but are unlucky enough to store fat viscerally. “What a dreadfully dire consequence of gaining a few kilograms as you march towards middle age.”

Most of us don’t have access to the equipment that can accurately measure our fat ratios, but estimates are often made using bioelectrical scales or skin fold callipers.

They can be woefully inaccurate, as Auckland University students and friends Eleanor Day and Ottilie Morrison, both 21, can attest.

Day’s gym did a bioelectric impedance test using scales which sent a small electrical impulse through the body to distinguish lean from fat. She was told she was “really fat inside”, had a total body fat of 30 per cent and should exercise more. Morrison’s gym did her measurements using callipers, and told her she had 17 per cent body fat – the physique of an athlete.

We decided to put the women, and two other volunteers, through the DEXA scanner at Auckland Hospital’s body composition laboratory to check (see below).

While Day’s body fat was 31.5 per cent, her levels of visceral fat were, in fact, extremely low – just seven per cent of her 1.1kg of abdominal fat. Morrison, despite an overall body fat of 39 per cent and a BMI that puts her in the overweight range, also had a low ratio of visceral fat – just nine per cent of her 1.9kg of abdominal fat.

Our other two guinea pigs, however, weren’t so well off. Despite having almost the same total fat as Morrison, 32-year-old Scarlett Jiang had a higher ratio of visceral fat at 30 per cent, while Andy Hammond, 45, a type 2 diabetic, had lower total fat – 35 per cent – but 50 per cent of his 4.9kg of abdominal fat was visceral.

“Most individuals with metabolic syndrome have fat stored in the wrong place, irrespective of their BMI,” says leading international researcher Jean-Pierre Despres, from Quebec.

“Maybe putting on visceral fat is a marker of the relative inability of the subcutaneous fat to act as a protective metabolic sink. So when we’re sedentary and have this lousy lifestyle and access to energy-dense food, some of us are able to put on subcutaneous fat and somehow get away without complications, whereas others gain less subcutaneous fat and become very sick because they store fat at undesired sites such as the liver, heart, skeletal muscle and so on.”

What makes some people store fat in safe places, and others not, is a question researchers still struggle with. Obviously genetics are important, but the challenge for these scientists is to work out how food can be adapted to reduce visceral fat and increase blood sugar control.

Professor David Cameron-Smith: “It is fundamentally important to invest in areas that impact on people’s health.”

The first few years of research for Poppitt’s group will involve trying to better understand the characteristics of people who do or don’t have diabetes. She says they’ll take a range of samples from healthy people, diabetics and “people in the middle” to examine their blood, liver, adipose tissue, and muscle and search for biomarkers that may predict risk. Different types of foods will then be tested to see if they alter the biomarkers, with vegetable or fish-based proteins a particular area of interest.

A big international trial is already under way to look at whether higher carbohydrate or higher protein diets are better for pre-diabetics and Poppitt says the High-Value Nutrition goal will not be to recommend a particular diet or food, but to identify food components, products or extracts that can improve the metabolic outcomes for people who struggle to lose weight. With obesity and diabetes increasing at a “cranking rate” in Asia – more than 60 per cent of the world’s diabetic population live there – the work has enormous export and economic potential, but also great relevance for New Zealanders, given nearly 30 per cent of us are obese.

At Otago, Lisa Te Morenga will explore how wholegrain foods influence health. Food scientists at the university will create and test breads and cereals made with whole or refined grains and then measure blood glucose and insulin responses in volunteers.

Products labelled “wholegrain” have to contain all the parts of the grain in the same relative proportions as they are in nature, but Te Morenga says there’s plenty of debate as to whether it’s beneficial to have the parts intact. She suspects size does matter. “At the moment a product like Cheerios cereal can call itself 100 per cent wholegrain, but if you were to look at it, you wouldn’t find any obvious grains in there. It’s much easier to make palatable products for consumers if you grind it up.”

She says food products that make it easier for people to make the right choices will become increasingly important. Many foods that seem healthy, really aren’t. “If you’re buying lunch and think about what you might get, sushi is high in refined carbohydrates, most sandwiches are in white bread like panini and even soup usually comes with a refined white roll.”

Bread is often served in thick chunks. “It’s not necessarily bad, but there’s a lot of it and it’s very easy to eat too much. You might be having the equivalent of four or five slices at once and it’s a better idea for someone with diabetes or pre-diabetes to limit it to two serves at lunchtime and fill up with vegetables, fruits and lean protein, rather than bulking up on breads.”

She says people should try to focus on eating more of the right foods, rather than concentrating on weight loss alone. Researchers at the university last year compared the metabolic outcomes in two groups of volunteers getting the same amount of sugar from fruit or from soft drinks. While there was no weight change, the fruit group tended to have lower blood pressure, and the men had lower levels of uric acid. High uric acid is linked to both gout and diabetes.

Te Morenga’s work made international headlines in 2011 after she published a study showing women lost more weight and improved their metabolic risk on a high-protein, high-fibre diet rather than a standard low-fat, high-carb regime.

Genetics, epigenetics, diet, environment – if research in health and nutrition wasn’t complicated enough already, another key player entered the picture in the late 1990s and has since threatened to steal the show.

It’s our microbiome – the trillions of ever-changing microorganisms in our internal ecosystem that have been linked with a raft of auto-immune, allergic and inflammatory conditions as diverse as asthma, obesity and cancer. But by manipulating the relative proportions of our gut bacteria, by promoting the good ones and reducing the bad, can scientists help to turn the tide of ill-health?

“We need to think about designing foods from the inside out,” Jeffrey Gordon of Washington University in St Louis told Scientific American last year.

In 2013, Gordon’s team published a series of experiments on genetically identical baby mice raised in a germ-free environment. The scientists then populated their guts with intestinal microbes collected from obese women and their lean twin sisters. Though the mice consumed the same diet in equal amounts, those with the bacteria from the obese women grew fatter than those with the bacteria from the thin ones.

When the animals were housed together, however, both groups stayed lean – evidence that the fat mice probably picked up some of the gut bacteria of the lean mice by eating their droppings. “Taken together,” Gordon told Scientific American, “these experiments provide pretty compelling proof that there is a cause-and-effect relationship and that it was possible to prevent the development of obesity.”

It’s astounding stuff, and therefore no surprise that our microbiota will be under the microscope in the High-Value Nutrition project, too. But here, researchers will be focusing on its role in immunity and gut health.

We’re all born with different populations of microbiota and only now are scientists realising the health trajectory this might set us on. Babies born to mothers who have a Caesarean section, for example, have a different bacterial profile, being colonised by fewer species – while babies born naturally acquire more species in the birth canal. Generally speaking, the more diverse your gut bacteria, the better off you are.

In a book out last year, Missing Microbes, New York professor and microbiome expert Martin Blaser said there was evidence antibiotics are not only changing the makeup of our gut bacteria, but are also making us fatter.

In mice experiments using DEXA scans, animals fed antibiotics had about 15 per cent more fat than others, and retrospective analysis of longitudinal research following more than 14,000 children from birth found those who had antibiotics in the first six months of life became fatter.

Otago University professor of medicine Richard Gearry: “If I‘d said five years ago that the bacteria in your gut may determine whether you were fat or not, people would have said, ‘That’s ridiculous, you’re joking.’ Now we accept that maybe it is true.”

For Christchurch Hospital-based gastroenterologist and Otago University professor of medicine Richard Gearry, the role of our gut bacteria is “the final frontier” when it comes to health. “If I’d said five years ago that the bacteria in your gut may determine whether you were fat or not, people would have said, ‘That’s ridiculous, you’re joking.’ Now we accept that maybe it is true.”

Gearry’s areas of expertise include Crohn’s disease and irritable bowel syndrome, two conditions thought to be heavily influenced by gut microbiota.

In the mid-2000s in Paris, gastroenterologist Harry Sokol discovered that tissue samples removed from patients with Crohn’s had relatively fewer amounts of a common bacterium. When the bacterium was transferred to mice, it protected them against intestinal inflammation.

Gearry’s research in Canterbury has discovered the region has the highest incidence of Crohn’s in the world, with 26 cases per 100,000 – a sharp jump on the 16/100,000 figure he found when researching his PhD in 2004. While the increase is large, rates of inflammatory, autoimmune diseases in general – type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s – are rising internationally, with most scientists favouring the “hygiene hypothesis” to explain it.

We live in a clean environment, awash with antibiotics. From an infection point of view, there’s not much happening that’s going to challenge our immune system – leaving it sitting there, twiddling its thumbs. And when the immune system gets bored, it simply attacks the wrong thing – healthy body tissue – by mistake.

In the gut, says Gearry, the body’s immune system is like the Dalai Lama. Despite billions of bacteria living there, it’s very tolerant. When inflammatory bowel disease strikes, it’s like having Paul Henry move in and, almost literally, shit-stirring.

The focus of Gearry’s work in the High-Value Nutrition study will be irritable bowel syndrome, which, though it affects one in six women and one in nine men, is still not well understood in its various forms.

Patients who’ve had colonoscopies and a diagnosis of irritable bowel will, among other studies, have gut and fecal microbiota samples analysed, and keep food diaries to examine the triggersand course of the disease. “We may find there is up- or down-regulation of various types of genes and cell-types that reflects the different things we eat. Unless we understand the basic science behind it, it’s very hard to come at it from the [food] product end.”

With 70 per cent of the function of our immune system associated with the intestinal tract, interactions between the diet, the microbiota and immunity is another key part of the science challenge. They have been a focus of Well-ington scientist Liz Forbes-Blom’s career for more than a decade but under the new research project, the target will be respiratory health and cold and flu infection.

Among foods that have already shown some promise in the lab against asthma and respiratory inflammation are fruit extracts – particularly from blackcurrants and boysenberries.

Like Gordon, Forbes-Blom’s team at the Malaghan Institute has mice that are genetically identical and live in identical environments, but have different gut bacteria. Her work will investigate the effects of manipulating the microbiota – for example with antibiotics – on immune responses to infection.

Malnutrition, she says, is the most common cause of a failing immune system, leaving it incapable of fighting infections such as colds and flu, and nutrition is one of the most accessible, cost-effective and underrated ways of boosting it.

Nutritional candidates that could change the makeup of gut bacteria include probiotics (the so-called “good” bacteria found in fermented foods such as yoghurt), prebiotics (non-digestible fibre that good bacteria use as food) and the combination of those two, known as synbiotics. Among the foods that have already shown some promise in the lab against asthma and respiratory inflammation are fruit extracts – particularly from blackcurrants and boysenberries.

Plant & Food Research scientist Roger Hurst says because the same immune pathways are activated in a number of allergies, it has implications for other conditions including psoriasis, eczema and hay fever.

The research has huge potential for the millions affected by air pollution in heavily industrialised Asian countries, where face masks are a common sight in the streets. “If you can manage the inflammation caused by pollution, you could potentially create a product for the Asian market because they are crying out for it,” says Hurst.

The “key performance indicator” for the High-Value Nutrition project is to add $1 billion to our economy by 2025. With food accounting for $25 billion in exports already, that’s not an unrealistic goal, Cameron-Smith believes. “The ultimate high value is foods that have substantiated health benefits – we can say these are good for you and sell it on that basis. New Zealand can promote to the world what it is as a country. Everything that leaves New Zealand should have in some way a health benefit. It’s what we do well.”

Progress in the challenge will be assessed at the halfway mark and if it’s not up to the mark, the money pin could be pulled. However, even if the $1 billion goal isn’t reached, says Cameron-Smith, the government’s investment won’t have been wasted. “We will have given countless thousands of people the opportunity to improve their health.”

Obesity, he says, is “the megatrend of the world. We talk about obesity, but in reality, everybody is getting fatter and it’s this shift in fatness that’s driving this massive cost.”

But at what point does the slide into ill-health begin? “If we can predict that, we can identify ways to stop it.”

For the Kiwi scientists, that is the billion-dollar question.

Inside Out

We know what we look like on the outside, but what about on the inside?

We recruited four guinea pigs with very different body types and took a look, thanks to new technology available at the DEXA body scanner at Auckland Hospital’s Body Composition Laboratory. The lab’s director, Associate Professor Lindsay Plank, says new software on the scanner now enables it to tell the difference between overall fat and visceral fat, which is linked with diseases such as diabetes.

While Plank says there’s no ideal number we should be aiming at for visceral fat levels, it’s common sense to think the lower the better.

Here’s how our participants fared:

Eleanor Day, 21, Student

**Eleanor Day, 21

Student**

Height: 1.79m

Weight: 72kg

Total body fat: 32kg (31.5%)

Abdominal fat: 1.14kg

Visceral fat: 73g (6.7% of abdominal fat)

Day was told after tests at her gym 18 months ago that she was “fat on the inside” and needed to exercise more. The scan proved otherwise, with her ratio of visceral fat the lowest of our group. “My flatmates would say that considering what I eat, I should be a lot fatter.”

Being tall, she says it’s easier to hide weight gain, reducing the incentive to diet and exercise more. She admits having a sweet tooth, enjoys a treat at the end of the day, and isn’t averse to the odd burger-and- chips takeaway. “Ice cream is my biggest weakness,” she says, and after six months’ exposure to Ben and Jerry’s while on a semester of study in the United States, she packed on 10kg.

“I eat a lot more than I should,” Day admits. Otherwise, her diet is generally healthy, with a strong emphasis on fresh salads and fish.

Ottilie Morrison, 21, Postgraduate student

**Ottilie Morrison, 21

Postgraduate student**

Height: 1.7m

Weight: 82kg

Total body fat: 32kg (39%)

Abdominal fat: 1.9kg

Visceral fat: 173g (9%)

After being told by her gym a year ago that she had the body fat of an athlete – around 17% – the results were a disappointment for Morrison, but there was also plenty of good news. Though she says she hates her “stocky” legs, from a health point of view that’s a far safer place to store fat than around the tummy, where her visceral fat ratio is low. “I’m quite muscly so I’m quite chunky.”

Her diet motto is “everything in moderation” and though she’s a sucker for ice cream, she binges on fruit and popcorn and shuns fizzy drinks. “I definitely want to become more toned and fit so I limit myself in what I eat.”

About two years ago, she began working out four to six times a week and also runs regularly. The regime has helped her lose 12kg. “I’m a work in progress,” she says.

Andy Hammond, 45, Digital sales manager.

**Andy Hammond, 45

Digital sales manager**

Height: 1.96m

Weight: 125kg

Total body fat: 43.5kg (34.6%)

Abdominal fat: 4.9kg

Visceral fat: 2.4kg (50%)

Hammond was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes about two years ago and is on medication. He says he’s struggled with his weight since piling on the pounds when he moved to the UK as a 23-year-old. “I started drinking a lot and didn’t do too much about my physical health.”

His weight has yo-yoed a few times since then, but he’s now on a fitness regime that has seen him lose about 1kg a week for the past two months. He stopped drinking a year ago and now runs regularly, completing an 8km run in mid-March in 54 minutes.

He says the slightly disappointing scan results are a big motivation to keep losing weight. And realising exercise alone isn’t enough, he’ll now try reducing his portion sizes, particularly at dinner.

Scarlett Jiang, 32.

**Scarlett Jiang, 32

Assistant accountant**

Height: 1.64m

Weight: 75kg

Total body fat: 30kg (40%)

Abdominal fat: 2.5kg

Visceral fat: 757g (30%)

Because of her Chinese ethnicity – she moved here from northern China as an 18-year-old – Jiang is at higher risk than Europeans and Pacific Islanders of the metabolic consequences of being overweight.

She describes her exercise regime as “relaxed” and her diet as “balanced – I eat everything, there’s nothing I leave out”. For lunch and dinner, she has rice, meat and vegetables, and breakfast is usually Weet-Bix with milk and raisins.

She does Pilates and walks 25 minutes each way to work and back daily, but admits to a penchant for ice cream; in summer she’ll have it up to five times a week, also cheese and dairy products. “I thought the calcium would be good for my bones.” Overweight as a child, she grew up eating a lot of ice cream, too. “My grandfather spoiled me rotten.”

She always has full-fat milk but will now opt for lower-fat options and try to increase her exercise.

Words by Donna Chisholm

Photos by Ken Downie