“This is not a lunchroom”, warns a sign in block letters, but the tantalising smell of chicken, potato and leek soup is oozing out under the door.

Inside, an old-fashioned crockpot is bubbling on the table, next to bowls of green salad, hummus, and a bag of jet plane lollies for the kids. Dr Melanie Cheung, who’s manning the toasted-sandwich maker, rips open a tin of spaghetti – her trademark MAC Russian Red lipstick a slash of colour against the jet-black of her clothes and hair.

“I’m always worried there’s not going to be enough food!” she says, loading up slices of bread and passing round mugs of steaming homemade soup, after a karakia giving thanks for the meal.

Already it’s been a big day for this new intake of recruits on Cheung’s “FightHD” trial for people at risk of Huntington’s disease, an inherited neurodegenerative disorder that affects one in every two children – ripping through the generations like a genetic plague. The group, all members of the same extended family, left south of Auckland at 7am to drive into Auckland University’s Centre for Brain Research in Grafton, detouring to pick up an auntie on the way. One young woman with two small children has travelled up from Hamilton and will head back home tonight.

Melanie Cheung: “We don’t want to just collect data, but make sure people are well cared for. It’s a horrible, horrible disease.”

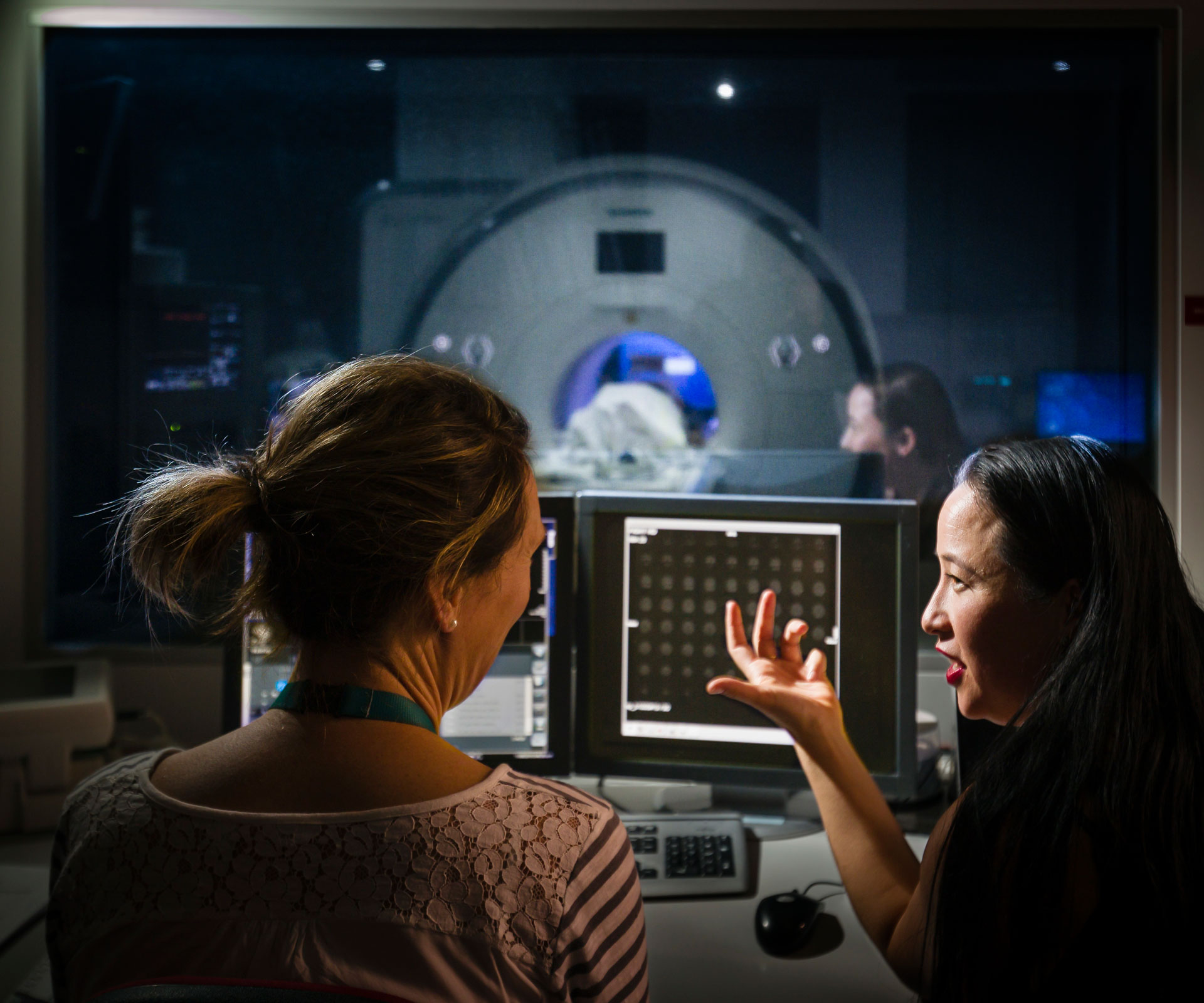

By noon, blood samples have been taken, and detailed psychiatric and psychological assessments are under way. But there’s still one more MRI scan scheduled after lunch and a few more tests to complete before they can finally cluster around Cheung’s laptop for their first look at what makes her research project so revolutionary.

Until now, there’s been no treatment for the cognitive decline that can start to affect people with Huntington’s in their 20s or 30s – years before the jerky, involuntary movements and mobility problems typically associated with the condition. Nor has a way been found to slow the inexorable progression of the disease. Cheung hopes to do both, using the principle of neuroplasticity – the brain’s ability to “rewire” itself – to beat Huntington’s at its own game.

What she’s come up with is a computer-based programme that takes the pop-science of brain training to a far more complex level. Using a series of targeted exercises to both stimulate and strengthen key pathways in the neural circuitry, she believes it’s possible to shore up the mental processes most vulnerable to attack.

And that, right there, is the simple beauty of it. No drugs, no surgery, no side effects. If Cheung’s gut instincts are right, all it might take is an internet connection and 30 minutes a day to stay one step ahead of Huntington’s – or at least buy extra time. For families like this one, who have four generations living in the shadow of the disease, it gives them something they’ve never had before. A fighting chance.

“We can treat some of the depression and anxiety, we can treat some of the motor decline, but there’s nothing we can do to stop the brain from dying,” says Cheung, who developed the project in collaboration with leading neuroscientist Professor Mike Merzenich, at the University of California, where she spent seven months working at his Brain Plasticity Institute on the back of a Fulbright award. “There isn’t even an ambulance at the bottom of the cliff.”

At one Huntington’s conference she went to, a woman spoke who had nursed her mother-in-law, her husband and one of their children.

“She was pleading to the scientific community to find a solution, because now she was staring down the barrel of having to nurse her grandchildren,” says Cheung, 38. “We’ve known the gene for Huntington’s for 22 years, and we’ve been trying to make drugs in cells and transgenic mice and translate it across to humans. Billions of dollars have been invested in that process, and none of them work. Shouldn’t we be trying something different?”

It’s not often you get to take a day off work, on doctor’s orders, to play computer games. Then again, it’s not often you find a world-class neurobiologist running a soup kitchen for her patients, either. But after spending her PhD in the lab, growing cells from brains post-mortem, Cheung decided she didn’t want to work on drugs or animals, and she definitely didn’t want to work on dead tissue anymore.

All FightHD trial participants undergo an MRI scan so their neural circuitry can be analysed. It’s difficult

to describe what goes wrong in a Huntington’s brain, says Cheung. “Almost everything does.”

“I realised I had to figure out how to work with live humans,” she says. “I was ready to work with people.”

And when you’re Maori, she laughs, that means setting aside a decent chunk of your funding budget for food (her creamed paua is legendary). Cheung’s mother is Maori (Ngati Rangitihi) and her father is Tahitian-Chinese. “There’s something special about breaking bread with people,” she says. “It’s part of our culture. But they also give to us and feed us in different ways through our research and by telling their stories.”

Cheung has a story of hope for those who come to sit at her table, with what Mike Merzenich describes as ‘the sword of Damocles” hanging over them. Until now, many of them didn’t even have a name for the sickness that’s taken their grandparents, their aunties, their cousins – and might one day carry off their children.

It’s particularly cruel and frightening, this genetic flaw that attacks a person’s brain in the prime of their life, slowly eroding their ability to think, to remember, to swallow, to speak, to smell, to control the wild movements of their body or tame the emotional tumult in their mind, until the very essence of who they are is lost deep within the disease.

Drugs can help with the depression or psychosis, and manage some of the physical symptoms, such as the involuntary, writhing motions known as chorea (derived from the Greek word for dance). But until now, there’s been nothing to protect against the inevitable cognitive decline as the brain starts to decay, affecting everything from memory and impulse control to processing speed and mental agility. It’s this deterioration Cheung believes she can delay – and even potentially reverse. “If we can fix those things, or at the very least slow them down, can we prevent some of the more awful things from happening altogether?”

There are few public “heroes” with Huntington’s, which affects roughly one in 18,000 people. No Michael J. Fox, Muhammad Ali or John Walker, as there is for Parkinson’s (a far more common condition); no Glen Campbell, Ronald Reagan or Rita Hayworth, who all went public after their diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Just a few decades ago, people with “HD” ended up in psychiatric wards, often shunned and routinely misdiagnosed.

Even today, less than a third of those at risk choose to find out whether they’ve inherited the DNA stutter that triggers the disorder, although a simple blood test has been available since the HTT gene responsible was discovered in 1993. It’s a knowledge not everyone can bear; “survivor’s guilt” means the risk of suicide is high even among those who are negative.

A model showing the basal ganglia, deep structures of the brain primarily affected in Huntington’s disease.

All of us are born with two copies of the HTT gene – one from each parent – which codes for a protein that’s an essential building block for life (lab mice with both copies of the gene removed do not survive). That means every child who has a parent with Huntington’s has a 50 per cent chance of inheriting their mutated gene – so a positive test result has enormous ramifications for the wider family. There are no symptom-free “carriers” and the disease can’t skip a generation, but may develop progressively earlier as it’s passed down the line.

Early European settlers are believed to have carried the gene to New Zealand, but it’s in Maori communities, where large families are culturally valued, that the toll seems particularly savage. Through her research, Cheung has built a close relationship with eight extended whanau, from Northland to Invercargill. In one Maori family alone, it’s estimated 300 to 400 people are at risk.

Drawing on elders for guidance, she’s developed a framework of tikanga Maori protocols, which include lab practices to respect the tapu around handling human tissue. Travel costs are covered for those on the trial and ongoing support includes regular home visits and health checks. Not everyone wants to know if they carry the gene, so blood tests are analysed in the US and then blinded, so even Cheung isn’t privy to the results. “Whakapapa is important to Maori – who we are and where we’re from,” she says. “We don’t take it lightly when we work with genetic diseases.”

Participants are divided randomly into two groups and train for 30 minutes a day, working through a series of tasks that gradually increase in difficulty. Questions are also asked to track their emotional state of mind. Half follow a broad-based cognitive programme that gives the brain a general workout; the rest do specific plasticity training, which targets more complex processes. (Details of the exercises are being kept under wraps until the trial is complete.)

After 20 weeks, another round of assessments is made against the baseline data, and then again at 40 weeks, when those on the cognitive programme switch over. “We don’t want anyone to miss out,” says Cheung, who has a $1.2 million funding grant from the Health Research Council and is still recruiting Maori participants for her trial.

To protect the families’ privacy, we agreed not to identify anyone taking part in the research. But Aroha, the first person to sign up, is open about her positive status and hopes others will follow her lead. The eldest of 12 children, she lost her grandfather and some of her uncles to Huntington’s. Her mother, who was sectioned under the Mental Health Act, has also tested positive.

After 103 days on the programme, friends and family have noticed significant improvements in both her mood and memory. Her ability to concentrate and even her peripheral vision has sharpened. She’s also a healthy weight. “Looking back at photos, I’m shocked at how skinny I was.” She doesn’t drink or smoke; now her half-hour brain training is also part of her everyday wellbeing routine. “They told me it was too late for Mum, but it wasn’t too late for me.”

Folk legend Woody Guthrie. Police thought he was a vagrant when they picked him up wandering a New Jersey highway in the 1950s. He spent his final years in a state hospital, before dying of Huntington’s at the age of 55.

Aroha doesn’t have children – but her 36 nieces and nephews are all at risk from the rogue family gene. “It’s about the kids now,” she says. “Mum tried to hide this from us, but we need to be prepared and share this knowledge for the next generation.”

Angel, a youth worker in South Auckland, joined the trial a few weeks ago and is anxiously awaiting her test results. She was raised by her grandmother, who was diagnosed with late-onset Huntington’s in her 70s. “For me, finding out will help me challenge whatever comes.”

She says being part of the research has opened her family to a new understanding of Huntington’s, which she hadn’t known was a disease of the brain. “Some don’t want to be part of it; they’re afraid to know. But Nan, she’s our everything. We need to have a plan in place, for her and for ourselves. When the time comes, we need to know what to do.”

Neuropsychiatrist Greg Finucane, who’s on the research team, describes Auckland as an unexplained “hotspot” for Huntington’s. (Tasmania is another.) Over the past decade, the number of people affected across the region is estimated to have increased tenfold. For the Maori population, with its strong youth skew, he warns the disease could “kneecap some of the Maori renaissance”.

There’s evidence neuroplasticity is already occurring at some level in people with Huntington’s, says Finucane. Pre-symptomatic patients may perform normally in neuropsychiatric tests, but a closer look shows their brains are having to work harder. “So there’s a sense in which the brain is adapting itself to remain more functional.

If we can find ways to train the brain to do that better than it does spontaneously, then yep, we might be able to delay the onset.”

Professor Richard Faull.

Cheung was “quite bright” growing up in Edgecumbe, where her dad worked at the dairy factory and her mum stayed home with Melanie and her big sister. Her first biology lessons were on her grandfather’s farm. “You see it all happening; the cycle of life.”

By high school, being smart wasn’t cool anymore. Scraping through UE, she dropped out of Auckland University halfway through her science degree and had an “interesting” early 20s, working her way up through the hospitality trade to earn some decent money as a restaurant manager. “I was a little bit naughty,” she says. “A little bit lost.”

It was when she decided to give uni another go, and was taken on as a biology tutor with the Tuakana mentoring programme for Maori and Pasifika students, that the lights went on for her academically. By then, she’d also turned into a stroppy young Maori.

At the Centre for Brain Research, where she did her PhD with Professors Richard Faull and Mike Dragunow, she handed out photocopied chapters from books on Maori cosmology and decolonising methodologies. “They never missed a beat,” she says. “I told Richard I didn’t want to be his token darkie. He was fabulously offended.”

Faull, who is actually part-Maori himself (Ngati Rahiti, Te Atiawa) led the ground-breaking research that showed – against the accepted science of the time – that an adult brain can grow new cells. On a visit back to his hometown in 2007, he was approached by a Maori family struggling with Huntington’s disease who made a desperate plea for help. The next time he went down, Faull took Cheung with him.

By then, she’d already started developing her tikanga protocols and had decided she wanted to work with indigenous communities. So when she read about Mike Merzenich’s pioneering neuroplasticity work in the US on brain disorders, all the pieces fell into place.

Faull calls Cheung’s research project revolutionary. “There’s science out there just aching to be applied,” he says. “It’s a story of hope, of getting out of the lab and looking after people in their own environment – not looking at their brains after death. Mel pushes the boundaries in the most challenging ways. But she has passion, commitment and enthusiasm, and she loves life. That’s enough for anything.”

Jo Dysart, the only clinical nurse specialist for Huntington’s in Australasia and a key part of the FightHD team.

When Cheung sent Merzenich an email through his company website two years ago, explaining why she thought his brain-training exercises might work in Huntington’s disease, he was so impressed he invited her over to stay with him in California – and told her that if no one was home when she arrived, there’d be a key left under the mat. She spent her first day with him picking grapes on his Sonoma Valley vineyard, and then sat with the crème de la crème from the world of neuroscience around his dinner table.

“I told my wife it was one of the most intelligent and logically cogent considerations by a young scientist I had ever received and it would be sort of disgraceful not to help her,” says Merzenich, who has still never asked to see her CV. “I’d bet my house on the hypothesis that at the very least we can give [people with Huntington’s] more years of healthy life.”

At the end of July, Cheung heads back to the US. She’s keen to develop new exercises for her Huntington’s research and is working up other projects with Merzenich, who’s had impressive results using plasticity training to help people with schizophrenia. Their next target, he says, will be Parkinson’s disease.

He sees Cheung as having the potential to be a world leader in her field. “She has that kind of moxie,” he says. “Something I love about Mel is that she’s genuinely compelled to go do good. I can’t tell you how few scientists I run across who have that instinct.

“She’s not really young; it’s taken a whole lot of life to get here. But she’ll be a leader. Not in the lab, playing around with test tubes, but out there inspiring other people. She’ll know what to do.”

For more details on the FightHD trial, email study co-ordinator Emma Lambert at [email protected].

Words by: Joanna Wane

Photos: Adrian Malloch