Despite being half a world away in New Zealand, Mark Longley knew something was terribly wrong the day his beautiful daughter Emily drew her last breath.

“I remember driving around all day and hitting the curb,” recalls Mark, 50. “My wife Hilary was asking, ‘Are you OK?’ All day I had this horrible feeling I just couldn’t shake.”

Later that night, on May 7, 2011, Mark and Hilary were woken by a missed call at the dreaded hour of 2am.

“I cleared the message from Emily’s mother Caroline, and all I could hear was her sobbing and my daughter Hannah shouting in the background, ‘Emily’s dead! Emily’s dead! Emily’s dead!’ It was a blur after that.”

Mark phoned his parents in Bournemouth, on England’s south coast, where Emily was staying. A police officer at the house confirmed that 18,000km away, on the other side of the globe, his spirited 17-year-old daughter had been found dead.

“I thought, ‘That can’t be true.’ That morning, we’d chatted on Facebook. She was normal and happy – there was no hint about what was going to unfold.”

At first, the family was given only scant details.

“We thought it could be a sudden death, but Emily had been out in New Zealand only a week earlier – she was fit and looked amazing. I knew her body wouldn’t give up on her like that.”

Hannah adds, “She seemed happy. She was happy to be here, spending time with us. She even liked seeing my dog, who she never liked in the past.”

It would be several months before she and Mark – who lives in Auckland with Hilary and their three-year-old son Hunter – heard the full catalogue of domestic violence Emily had suffered at the hands of her controlling and narcissistic ex-boyfriend Elliot Turner, 20.

When Emily tried to end the relationship, Turner – the privileged son of wealthy jewellers who was known among his friends as “All Talk Turner” – strangled her in his bedroom at his parents’ house in Bournemouth.

As the judge would say during the trial nearly a year to the day later, Turner had decided that if he couldn’t have Emily, then no-one could.

After hanging up the phone that fateful night nearly seven years ago, Mark can’t recall much more, but he knows he didn’t sleep. The next day he, Emily’s mother Caroline and their daughter Hannah, then 15, boarded a plane for the agonisingly long flight to London.

Emily and her boyfriend-turned-killer Elliot Turner.

“Even then, I thought there must be a mix-up,” says Mark.

“It took me two years to accept that Emily was dead. Even after I saw her body in the morgue, lying under a purple sheet, I waited for her to jump up, say boo and laugh.”

The Longley family moved to Aotearoa when Emily was 10, largely for her health.

“Emily was one of those kids who was constantly sick,” recalls Mark, the managing editor of Newshub digital. “She had a form of osteoporosis and a lot of allergies, so we thought we’d get out of London for somewhere clean and green.”

The family settled on Auckland’s North Shore and for a while, Emily blossomed.

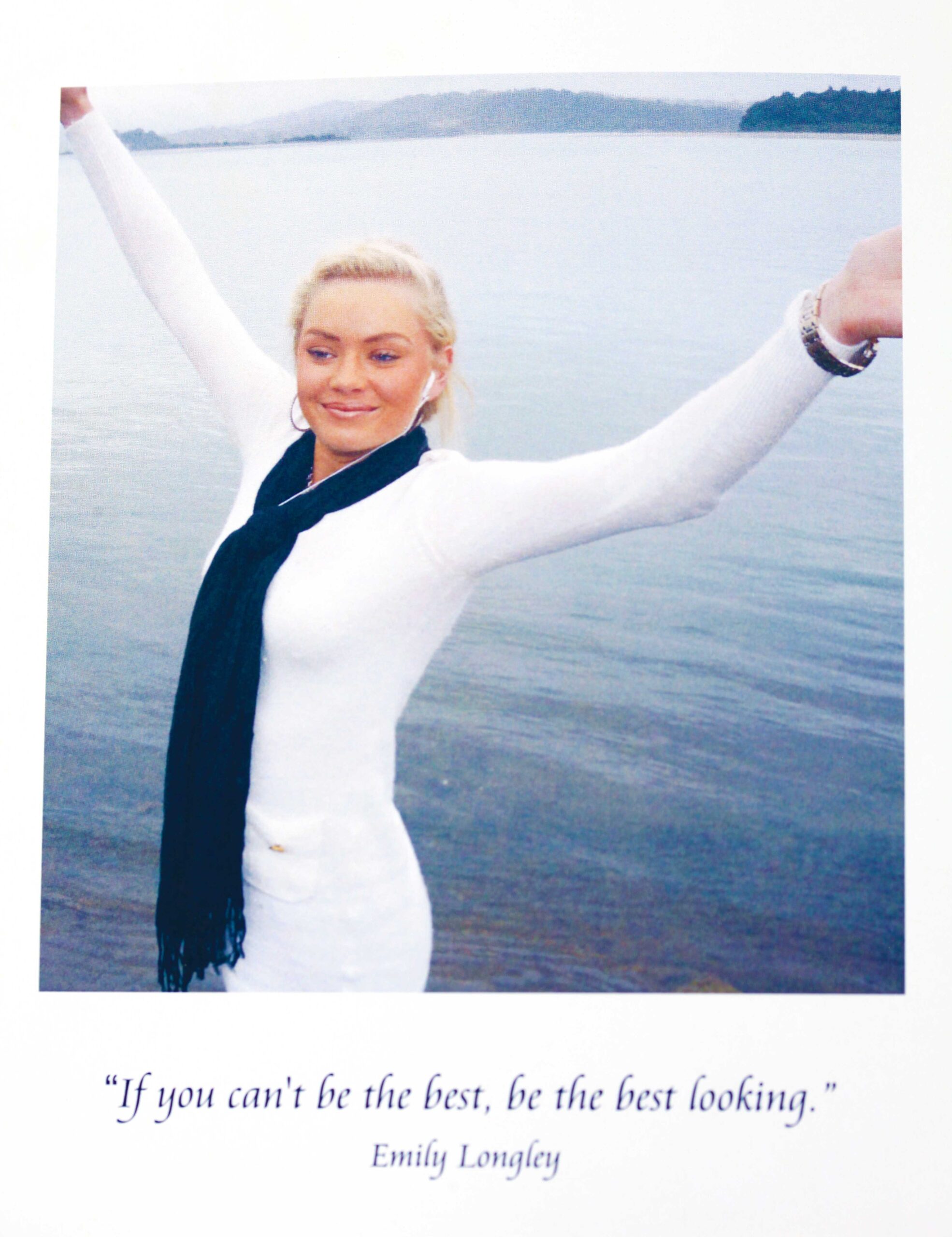

“People always focus on Emily’s beauty, but there was more to her – she was sweet and kind and loving,” tells Mark.

When Emily was 12, her parents separated and she spent her teenage years living between two homes while she attended Takapuna Grammar School. Mark and his daughter were close, but she could be a handful.

“Emily was determined – like a bull, she would charge full-on. It was hard to manage when she was young, but I thought it would stand her in good stead as an adult.”

Emily and her sister Hannah both had dual citizenship and in August 2010, when Emily was 16, she convinced her parents to allow her to return to the UK to live with her paternal grandparents and study business at Brockenhurst College in Hampshire.

Emily thrived – doing well at school and working part-time at Topshop. But the fun-loving teen loved to socialise and often wouldn’t make it home at night. “If she wasn’t allowed out, Emily would climb out the window – she could always sniff out a party a mile away,” recalls Mark.

Her dad has found out since that Emily met Turner through mutual friends a week before her 17th birthday. Although he chatted to his daughter morning and night via Skype or Facebook, she didn’t mention meeting someone new.

“Emily always had boys sniffing around, but she was a free spirit and never placed much importance on a relationship,” he tells.

Mark has now learnt that the litany of domestic abuse began almost as soon as they got together, yet throughout it all, Emily kept the shocking truth from those closest to her, including her family.

During the pair’s turbulent six-month relationship, Turner regularly called Emily a whore if she looked at another man and he hacked into her Facebook account to tell her male friends to clear off.

The court would later hear he threatened to kill her at least 15 times and once turned up to a nightclub with a hammer threatening to “smash her face in”.

A week before he finally choked the life out of her, Turner bashed her head against a table in a bar. Perhaps most disturbingly, though, he told his friends he was going to kill her and even practised his stranglehold on one of them.

Mark says, “They were a deadly combination – Emily was beautiful, but she was also feisty and wouldn’t tolerate things, and Turner just wanted a trophy girlfriend. The tragic thing is, if Emily hadn’t fought back, she may still be alive today.”

In April 2011, the month before she died, Emily returned to NZ for a three-week holiday. She’d been tearful on the phone a few times and Mark thought she was homesick.

“Of course, you over-analyse everything and, looking back, I wish I’d probed harder, but by the time Emily arrived, she was positive about her future, energised and loving.”

He remembers chatting briefly about Turner, but Emily seemed more interested in talking about her dream of one day working in fashion.

The last time Mark saw her alive, Emily was “energised and loving.”

After they both spent time in the Bay of Plenty with Hannah, Mark was sad to see Emily return to the UK, but he planned to meet up with her again later that year for the Rugby World Cup. To this day, he has kept a text message she sent after he dropped her at Auckland Airport: “It was so good to see you, love you.”

Mark says, “One thing that eats away at me is that Emily’s visit to New Zealand was so positive and yet it took Turner’s aggressive behaviour to a whole new level. I don’t think even Emily knew how much danger she was in.”

Fuelled by a slow-burning jealous rage, her on-off boyfriend had become convinced she was sleeping around in NZ.

“Turner got it in his head she was having an orgy on an island with an ex-boyfriend,” says Mark.

Emily’s family now know that while she was here, she was fielding threatening messages, where he vowed to “teach her a lesson” and “drown her in the bath”.

During that time, Turner also befriended Mark and Caroline on Facebook, telling them how much he loved their daughter. Mark tells, “I remember thinking, ‘This guy is trying too hard.'”

Elliot Turner’s parents Leigh and Anita tried to cover up their son’s crimes.

A year after her death, Emily’s family returned to the UK for the four-week trial. The day before, police told them of the full extent of the horror she’d lived through with Turner. “I walked out of our meeting and punched the wall,” recalls Mark.

A jury found Turner guilty of murdering Emily and he was sentenced to life imprisonment. His parents, Leigh and Anita Turner, were convicted of perverting the course of justice by trying to help their son cover his tracks.

It’s been incredibly difficult, but over the years, Mark has learnt how to not let Emily’s untimely death consume him. “I haven’t forgiven Turner, but I’m not angry any more,” he explains. “I can’t be. I have people who need me.”

Mark has found joy again with Hilary and their son Hunter. Meanwhile, Hannah, now 22, has a masters’ degree in psychology and works in suicide prevention.

She tells us, “Emily and I were normal sisters. We’d be fighting all the time, but at the end of the day, we always had each other’s backs. I try to be as positive as I can now that time has passed and the grieving process has had time to occur, and I’m always open and honest with people who ask questions or need advice in regards to Emily’s situation.”

On February 22 – what would have been Emily’s 24th birthday – Hannah posted on social media, “It’s been seven years since we’ve got to celebrate a birthday with her and this day never gets easier. She’s been on my mind a lot recently in light of the #MeToo and Times Up movements. We must use our voices to fight for those who were wrongfully silenced.”

Similarly, Mark is trying to save lives through his work as an ambassador with White Ribbon and a campaigner against domestic violence.

A few months after Emily’s death, he had a tattoo etched on his arm: “Let death not boast its conquering power, she’ll rise a star that fell a flower.” The words are borrowed, but the sentiment is his.

“I think of Emily as how she was and not what Turner did to her. To me, she will always be my beautiful, free-spirited and loving daughter.”