As New Zealand Woman’s Weekly prepares to mark its 85th birthday, we are taking a look back through our rich history, opening the archives to revisit some of the extraordinary, historic or downright unusual stories that have featured in the pages of this magazine.

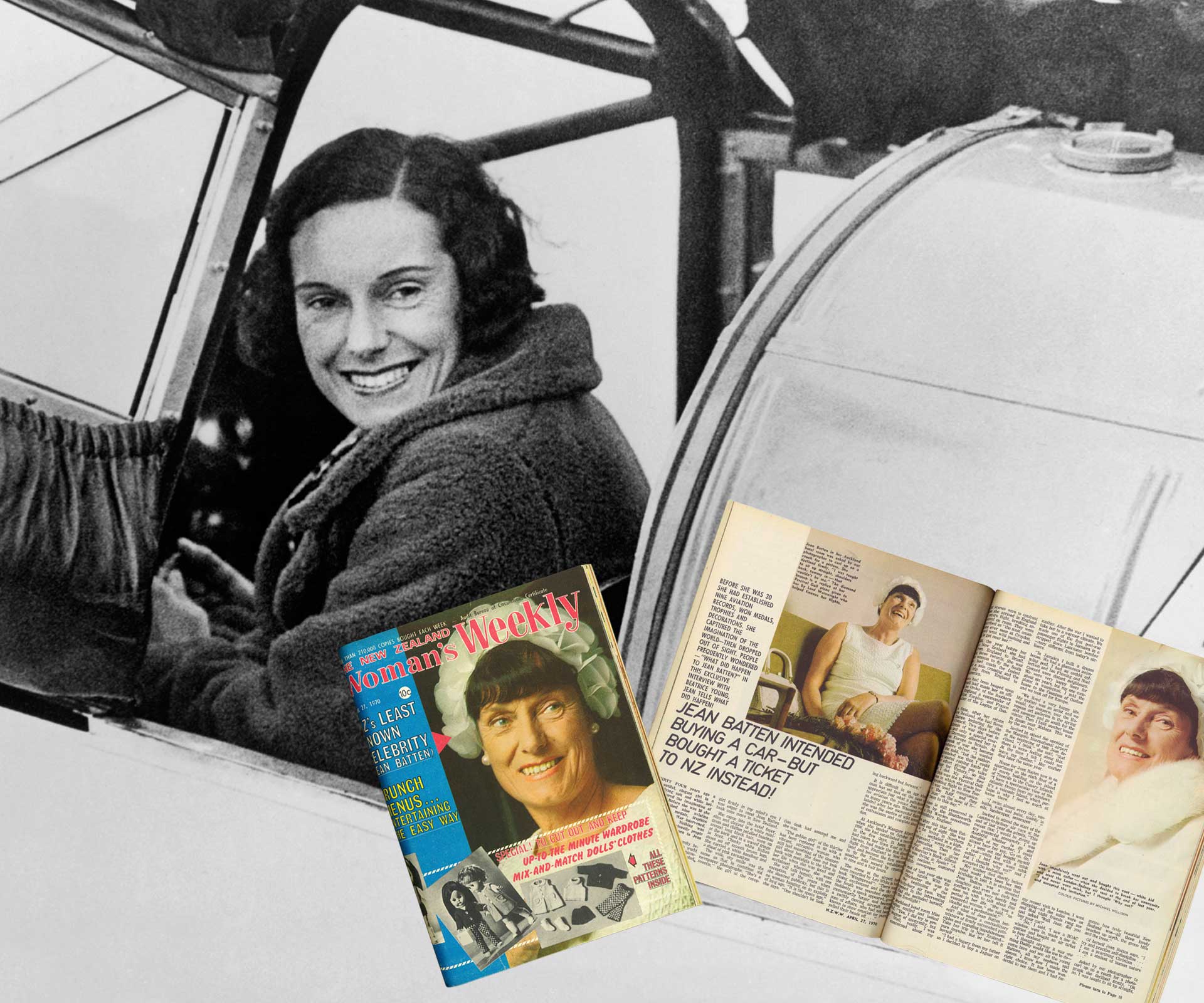

Each week, we’ll bring you one of these incredible tales – starting with this interview with New Zealand’s heroine of the skies, Jean Batten, which was published on April 27, 1970.

At the time of publication, a 60-year-old Jean spoke exclusively to Weekly reporter Beatrice Young during a visit to Auckland from her new home in Tenerife. She was a vibrant woman, who very much cherished her newfound anonymity abroad, but we questioned whether the call of home would ever bring her back home. It wasn’t to be – Jean died 12 years later, in Palma, Majorca. She was 71.

Thirty-four years ago, a beautiful, elegant girl in a bulky flying suit and white helmet captured the imagination of the world. Before she was 30, she had established nine aviation records, won medals, trophies and decorations.

War intervened, years went by. Nothing was heard of her. Occasionally people asked, What did happen to Jean Batten?

Thirty years of anonymity before one flashes back into world news is something of an achievement and I was eager to meet Jean Batten, back once more in New Zealand.

She came into the hotel foyer, slim and elegant in a white mini-dress and chiffon petalled bandeau around long black hair, worn up at the back and in a waved fringe in front.

The pioneering airwoman had disappeared from the headlines for 30 years, but the Weekly tracked her down when she returned home for a holiday.

Chunky white Italian shoes set off smooth brown legs. She carried a white handbag and a sheaf of pink carnations. The wide, shy smile was the same as that in countless old newspaper photographs.

“She’s a sweetie,” the girl at the reception desk had assured me, and she was.

The golden girl of the 30s has been replaced at 60 with a vibrant, attractive woman who still had something of the demure girl about her. She does not look back with nostalgia to the time in her life when she was feted and acclaimed wherever she went.

She will talk happily, with one exception, of the years when she shunned publicity, but this is no woman hanging on to exploits of long ago.

“It is the space age,” she says. “One shouldn’t be looking backward but forward.”

It is difficult in an age when man has set foot on the moon to appreciate just what a path-finder for aviation the young Jean was. Wherever she landed after her successful flight, she was the centre of wild scenes of enthusiasm and complete abandon.

At Auckland’s Mangere Airport when she landed on October 16, 1936, she had set a record in the five days, 21 hours it had taken her from Kent to Port Darwin, had made the first direct flight from England to New Zealand and become the first woman to fly the Tasman, establishing another solo record by crossing in nine and a half hours.

In 1935, the year before her flight to New Zealand, she had flown from England to Brazil, breaking three records. She was the first woman to fly the South Atlantic, had made the fastest time for a solo crossing and the fastest trip from England to South America.

Honours had been heaped on her. Brazil had made her an Officer of the Order of the Southern Cross; England a Commander of the Southern Cross, and France the Chevalier of the Legion of Honour.

From the New Zealand Woman’s Weekly archives.

For a time, after her return from New Zealand, she had flown around Europe lecturing for the British Council. Two days before the outbreak of war, she was in Sweden and only a special courtesy by Germany allowed her to fly across Europe to Britain.

At the outbreak of war, she became an ambulance driver.

“I wanted to fly,” she said, “but the authorities persuaded me that I could be more useful raising funds for the war effort giving pep talks for ‘Wings for Victory’, so this is what I did.

“My plane flew though [this was the Percival monoplane in which she made her record-breaking flight to New Zealand]. It was used in communications by the RAF and they anointed ‘Jean’ on the nose of it and it is still there to this day.”

After this, Jean Batten dropped out of sight. She was known to be living in Northern Jamaica, “…secluded in a high-walled compound,” wrote one Australian journalist.

Then her “who’s who” address was given as care of Barclays Bank, Gibraltar. She was living in Spain? “A recalcitrant recluse,” muttered one English newspaper.

At the end of last year, she was in the news again. With Sir Francis Chichester, she was to attend the beginning of the London to Sydney air race. What had happened in the intervening years? Had she secluded herself, shunned the limelight?

In her Auckland hotel room, Miss Jean Batten smiled and looked thoughtful.

“Yes, I did try to preserve a degree of anonymity, but recluse?

“Well, really, I was mainly concerned about my mother. I wanted to take her to a warmer climate. We made one of the first post-war passenger flights to Jamaica in a stripped-down Lancaster bomber – very different from today’s airliners.

“In Jamaica, I built a dream house. We had a glamorous swimming pool. I had an orchid collection, and Ian Fleming and Noel Coward were distant neighbours.

“We were very happy there for about six years, but my one complaint is wanderlust. I sold the house to the Countess of Onslow and we took off for Europe.

“We lived a very happy life. My mother was an artist and we would, for instance, tour the European art galleries in the spring and summe, and go south for the winter. Then I built another house by the sea in Spain, near Malaga.”

Jean Batten received an enthusiastic welcome at Croydon Airport after her record-breaking flight from Australia.

Jean was invited to attend the opening of the Mangere International Airport at the beginning of 1966 but she declined.

“I think that there is some feeling about this. At the time, I felt I could not leave my mother.” Her mother died later the same year.

Home for Jean Batten now is an apartment on the sixth floor of a 10-storey building on the island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands.

“I have a spectacular view of the Atlantic Ocean from my windows.

“It’s a volcanic island, which perhaps is why I feel so much at home there. I swim almost every day, sunbathe, walk and paint, mainly in oils, landscapes, seascapes…”

Invited to attend the start of the London-to-Sydney air race at the end of last year, she admits, ”This meant that I would be giving up my wonderful anonymity. I was doubtful whether to go and thought of my mother. I could almost hear her say, ‘Go on. Go.’ So I bought myself a coat – white with a mink collar. I had never worn mink but I thought ‘why not?’ and I accepted the invitation.”

Her mother died in 1966, shortly before what would have been her 90th birthday. It is obvious that Jean was a devoted daughter, and even now feels her mother’s death keenly and does not wish to talk about this period in her life.

“She was a wonderful woman, an idealist and a perfectionist.”

And what of Jean Batten?

From the New Zealand Woman’s Weekly archives.

She seems a contradictory mixture of firmly entrenched principles and engaging impulsiveness. Take her trip to New Zealand – pure impulse. But let her tell it herself…

“I had a legacy from my father, so I decided to buy a Jaguar on my recent visit to London. I went shopping – all the sales were on and that night, friends rang me and asked ‘Well, Jean, did you buy your car?’

“’No,’ I said, ‘I saw a BOAC window, went in, made a few inquiries and bought an air ticket to New Zealand.’

“I thought it was one thing Daddy would like me to do – come here and see all the young Battens, all my nephews and nieces.

“I know now I made the right choice. It has been wonderful to see them and I had forgotten how truly beautiful New Zealand was – all those lovely beaches up north, the green hills and the trees.”

Of herself, Jean Batten says, “I try and practise self-discipline. I am a practising Christian. I am a student of human nature…”

Asked by our photographer to curl up on a couch for a photograph, she declined firmly, “Oh, no. I was taught to sit up straight, shoulders back, tummy in. That wouldn’t be me.”

She does not smoke. “When I couldn’t get Turkish cigarettes, I stopped.” Drinks sparingly – “I like good wine with my dinner, though,” and is looking forward to sampling “some of those wonderful Bluff oysters”.

She admits to being vain.

“I will never fly solo again because I am too vain to wear spectacles.”

She is genuinely fond of children and was obviously moved by the reception given to her by children at a Mangere school named after her. Together, with the official bouquet, was one of some four or five flowers, carefully wrapped in waxed bread paper and tied with what had probably once been a hair ribbon.

“It’s sweet,” she said.

She has never married but agrees she was engaged five times, and smilingly explains the broken engagements as “Oh, a matter of choice.”

Report has it that she broke off an engagement to a London stockbroker by radio when she was in the air midway between London and Australia.

She feels her visions about aviation 30 years ago have been realised.

“I felt that we who were making flights then would be followed in time by the airlines, that these would become common-place passenger flights. When I flew to London late last year, it was in a VC10 jet. I was invited to look at the controls. I felt as if I might as well have been in a space ship. It was all so immensely more complicated.”

She believes that in the future, airlines will use the Pacific more and that Auckland could well become a great Pacific junction.

Jean Batten flew the Percival Gull monoplane from England to Australia in five days, 21 hours.

Comparing her latest flight to New Zealand with her 1936 one, Jean Batten laughed and said, ”Oh, the difference! Then I had black coffee to keep me awake. This time, for the first time in my life, I closed both eyes in the air and went to sleep.”

During her visit to New Zealand this time, Jean has fulfilled “a wish and a promise” – a visit to Waitangi for the Waitangi Day celebrations.

“When I was last in New Zealand, Lord Bledisloe was presenting the land at Waitangi to the nation. He said to me then, ‘Jean, if you ever get the opportunity, go to see Waitangi at least once.’ I was tremendously impressed. It is a beautiful setting and a memorable celebration.”

“Tremendously impressed” by New Zealand’s internal airway, Jean flew as their guest to Milford Sound, and dropped small New Zealand and Union Jack flags and a horseshoe all attached to a tiny parachute on a peak named after her in Fiordland’s Ailsa Range. The flags were “in memory” of Colonel Peter Mackenzie of Walter Peak station who named the peak.

What of the future? Is it possible she might live in New Zealand, perhaps build another dream house? She laughed.

“Everywhere we went, my relatives would say, ‘Ah, there’s the site for Jean’s house,’ or, ‘Here’s Jean’s beach.’ Perhaps, if the airlines handed me free season tickets, I might. Anyway,” she said with quite a smile, “Life begins at 60. You thought it was 40, didn’t you?”

Later this year, she is to be the guest of British Airways when the Concorde has its trials and after that “who knows?”

Whatever the future for Jean Batten, if life is beginning at 60 for her, it is obvious she is looking forward to it and will tackle whatever it holds for her with enthusiasm.

Words: Beatrice Young