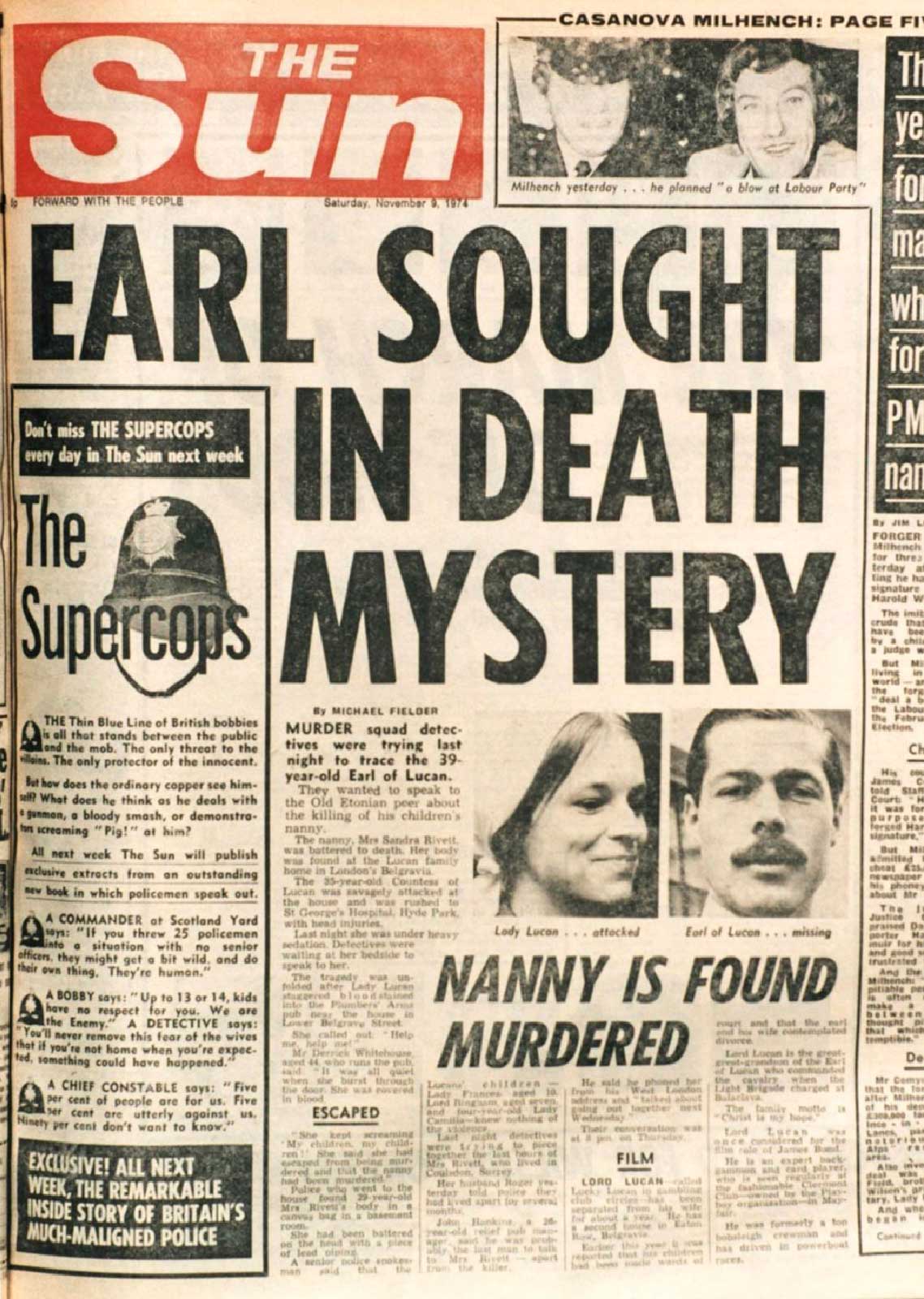

This week Lady Lucan died peacefully at home aged 80 – the same home her husband mysteriously disappeared from more than 40 years ago. Veronica, the Dowager Countess of Lucan, was one of the last people to see Lord Lucan alive before he vanished in 1974, at around the same time the family’s nanny Sandra Rivett was found murdered.

The mystery of who killed the 29-year-old nanny to Lord and Lady Lucan’s three children, and the subsequent disappearance of Lord Lucan has endured for more than four decades. In an interview earlier this year, Lady Lucan revealed all:

The Countess of Lucan lived alone in a pretty London mews house, with Buckingham Palace nearby on one side and a nondescript pub called The Plumbers Arms on the other. Both places have some significance in a story of aristocratic ruin that still fascinates, and may soon be definitively told.

On the night of November 7, 1974, a handful of drinkers were sitting in the pub when a distraught, blood-soaked woman burst through the door screaming: “Help me! He’s in the house! He’s murdered the nanny!”

Someone recognised her as Veronica Lucan, society beauty and wife of the 7th Earl of Lucan, but before she could say anything more the 34-year-old Countess fell unconscious to the floor. She remembers nothing else before waking up in hospital.

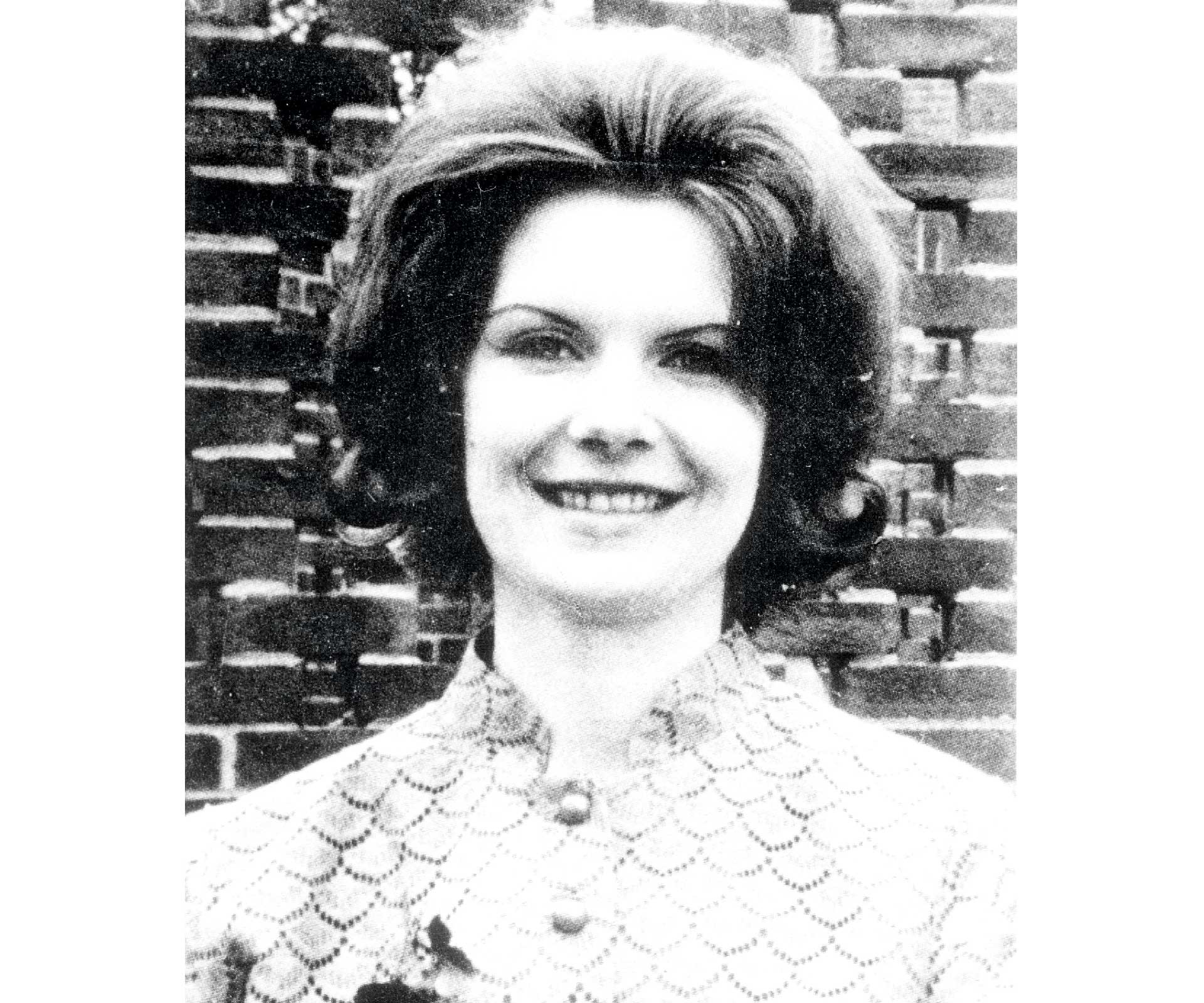

The nanny – Sandra Rivett

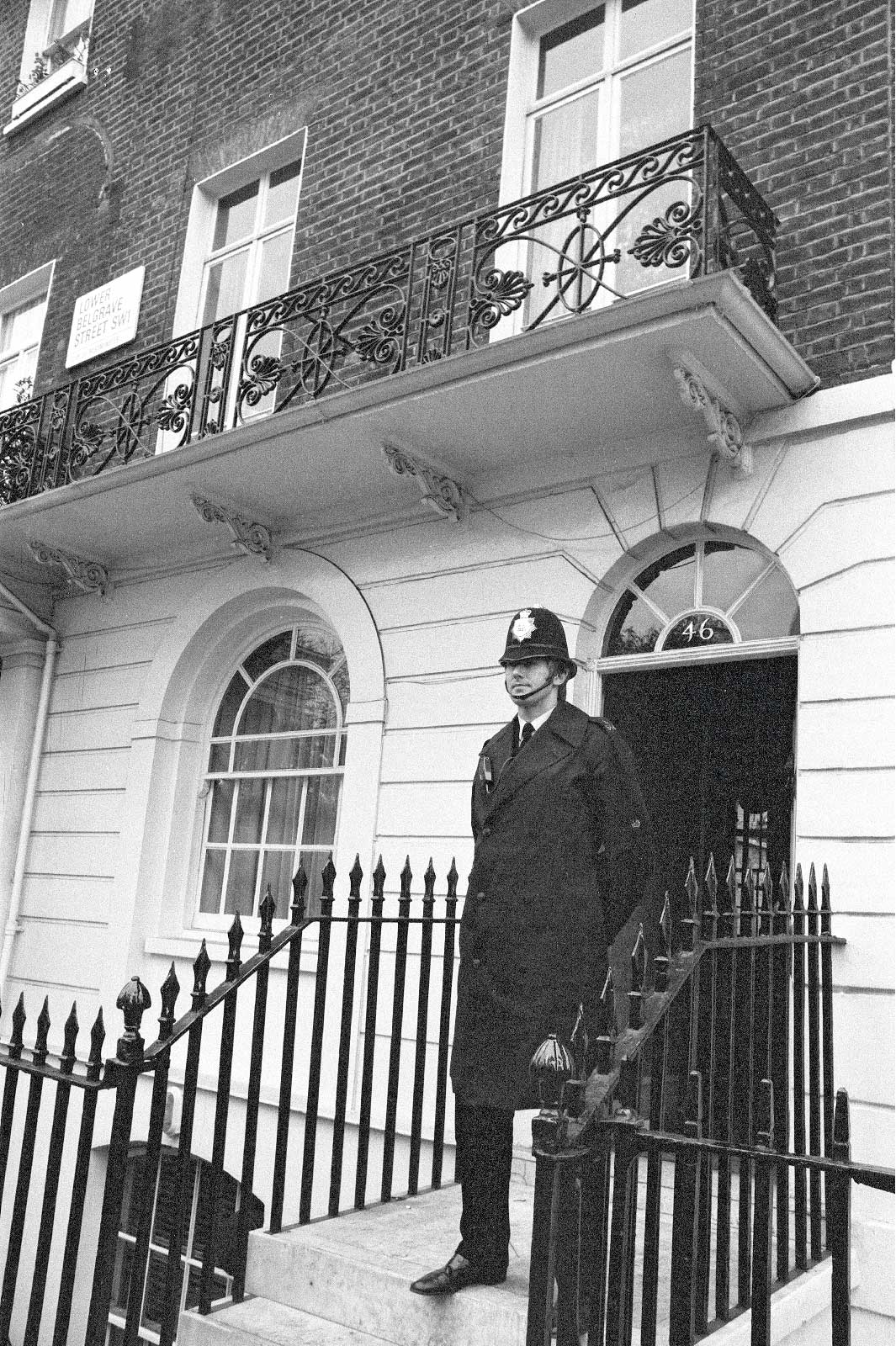

When the police arrived at the Lucans’ grand, four-storey house nearby in the heart of Belgravia, a grisly scene awaited.

The basement windows were splattered with blood, and by the dim light from the scullery they could see more blood on the walls and floor. Behind the door was a large linen mail sack, which was found to contain the bludgeoned body of the Lucans’ 29-year-old nanny, Sandra Rivett. A half-metre length of lead pipe, wrapped in bloodied tape was lying on the ground.

The Lucans’ three young children, Frances, 10, George, seven, and Camilla, four, were all in their beds, unharmed.

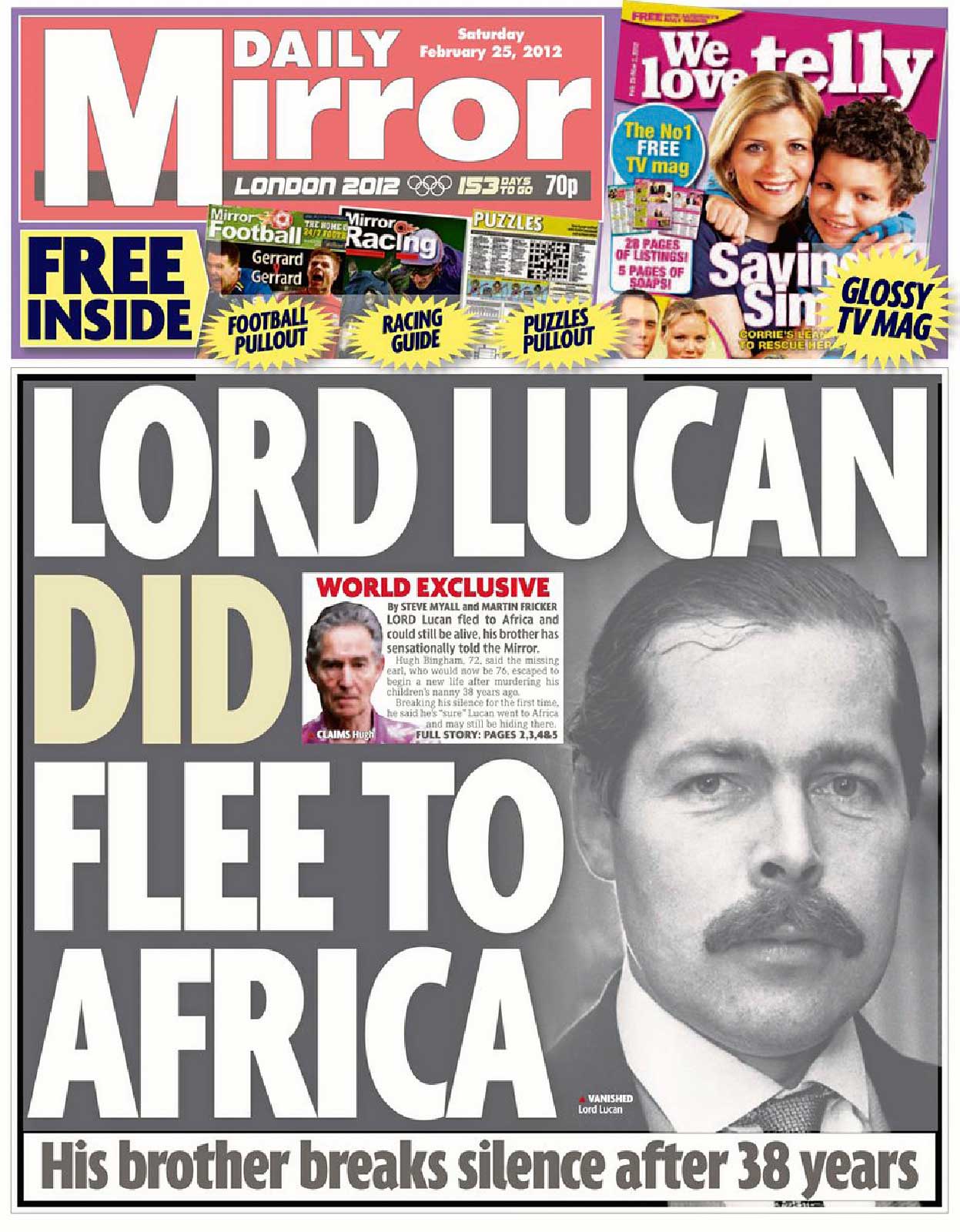

Lord Lucan was nowhere to be found – a situation that hasn’t changed in the 43 years since. His disappearance and the unsettling events that preceded it have become one of the great high society mysteries of modern times – the subject of countless investigations, theories and arguments.

The Lucan affair has sparked dynastic rifts, shattered friendships, and turned some of the most prominent figures in British society against each other. Now – after rejecting all previous entreaties – Veronica, 79, has agreed to write her own version of the story.

The scene of the crime

An enduring mystery

“From the beginning, I never really wanted to talk about it,” she tells me during her regular morning stroll around nearby St James’s Park, “but other people wouldn’t leave it alone, and they got so many things wrong. I tried correcting them, but it just went on, and in some ways it has got worse over the years, so it may be better if I have my say.”

White-haired, slender and elegantly dressed, Veronica still bears on her forehead the faint, filigree scars from that November night.

“I suppose they help remind me that you can’t just lock those memories in an old trunk,” she says. “So it’s probably better to do this while I’m still here.”

She adds, with a thin smile: “After all, isn’t the wife supposed to have the last word?”

Veronica in London in 2014.

While Veronica declines to give details, it is understood that she is working on a book and accompanying television documentary, scheduled to appear next year.

Last year a British court declared the Earl – who would now be 82 – to be officially dead. Yet he remains very much alive and kicking in the minds of those who believe this enduring upper-class whodunit has never been properly solved.

Barely a year goes by without a supposed sighting of the vanished nobleman somewhere in the world – living among tribesmen in South America, on a farm with a pet possum in New Zealand, or selling beach trinklets in Goa – or the emergence of a new theory arguing for either his innocence or guilt.

Journalist William Coles, the author of one of several books on the case, says: “Finding Lucan would be the Moby Dick of world exclusives. What keeps the story alive in the public eye is not so much the murder as what happened afterwards. The evidence is so sparse, so scant, pretty much any scenario is feasible.”

Known as “Lucky” Lucan, the Earl was a gambler, shown here playing cards in a London club. He was in debt and being hounded by creditors when he vanished.

Who was Lord Lucan?

Although Lord Lucan cut a refined and raffish figure in London’s clubland, where he spent much of his time playing roulette and blackjack, the murder inquiry quickly uncovered a troubled side to his life. He was heavily in debt, under siege from creditors and, having recently separated from Veronica, was locked in a costly legal battle over custody of their children.

John Bingham had been born into one of Britain’s most illustrious families, attending Eton and serving as a Lieutenant in the Coldstream Guards, whose regular duties at Buckingham Palace brought him into social contact with royalty. He later used these connections to ease his way into the louche world of high society gambling.

Yet for all his blue-blooded pedigree, John had inherited relatively little money upon the death of his father, George Bingham, in 1964. The Lucans’ ancestral landholdings had been largely sold off, and while there was enough for John to keep up the pretence of wealth and ease, his compulsive gambling gnawed away at what was left.

Veronica Duncan, raised in South Africa, was the daughter of a distinguished British army officer. Expensively educated, pretty, and popular on the debutante circuit, she had met John at a country house party in Buckinghamshire in the early 1960s, and after a romantic holiday at a friend’s villa on the French Riviera, he proposed.

“When we became engaged,” Lady Lucan told me, “he said he could not change, and I accepted that and did not try to influence him. But his life did change. It became worse, although the changes did not seem evident to him.”

The police quickly deduced that on the night of the murder, Lord Lucan had gone to the family home intending to kill Veronica, but in the darkness and confusion had mistakenly murdered the nanny instead. Having realised his error, he lay in wait until Veronica came downstairs to investigate the noise, then sprang from the gloom and attacked her, too.

Lord Lucan, powerfully built and towering over his wife, swung the lead pipe with all the strength he could muster.

In a previous interview, Veronica told me how she believes she survived:

“The thing was that John had hit Sandra so hard that the pipe bent. And this actually saved my life because when he attacked me he couldn’t land it with the same force. It was wrapping around my head rather than bashing through it. Also he hit me at the front where the bone is stronger. I don’t recall, for a moment, that it hurt, although I do remember what a strange feeling it was to be watching your own husband trying to kill you.”

Suddenly the pummelling stopped, and in a surreal reversion to gentleman-mode, Lucan helped his wife to her feet, and suggested: “Perhaps we’d better go upstairs and have a chat.”

They went to the marital bedroom, where Veronica lay groaning, while John, white-faced, paced the floor saying nothing. Eventually, she asked him for a wet flannel to wipe the blood from her face, and as soon as she heard the tap running in the bathroom, fled downstairs and into the street.

Lucan left the scene soon afterwards, and it is at this point that the real mystery of the “Murder in Belgravia” begins.

Alleged sightings of the runaway lord continued all over the world for decades.

An astonishing story

At around 11pm, John arrived at the Sussex home of his close friends Ian and Susan Maxwell-Scott.

In a state of high agitation, he told them an astonishing story of how he had been walking past the family home when he had seen an intruder attacking his wife. He rushed inside to help, but slipped on a puddle of blood, allowing the assailant to escape. Veronica had then become hysterical, accused him of trying to murder her, and fled.

What was he to do? The Maxwell-Scotts urged him to call the police immediately, but he said it would be better if he returned to London, and disappeared into the night. There have been no confirmed sightings of him since.

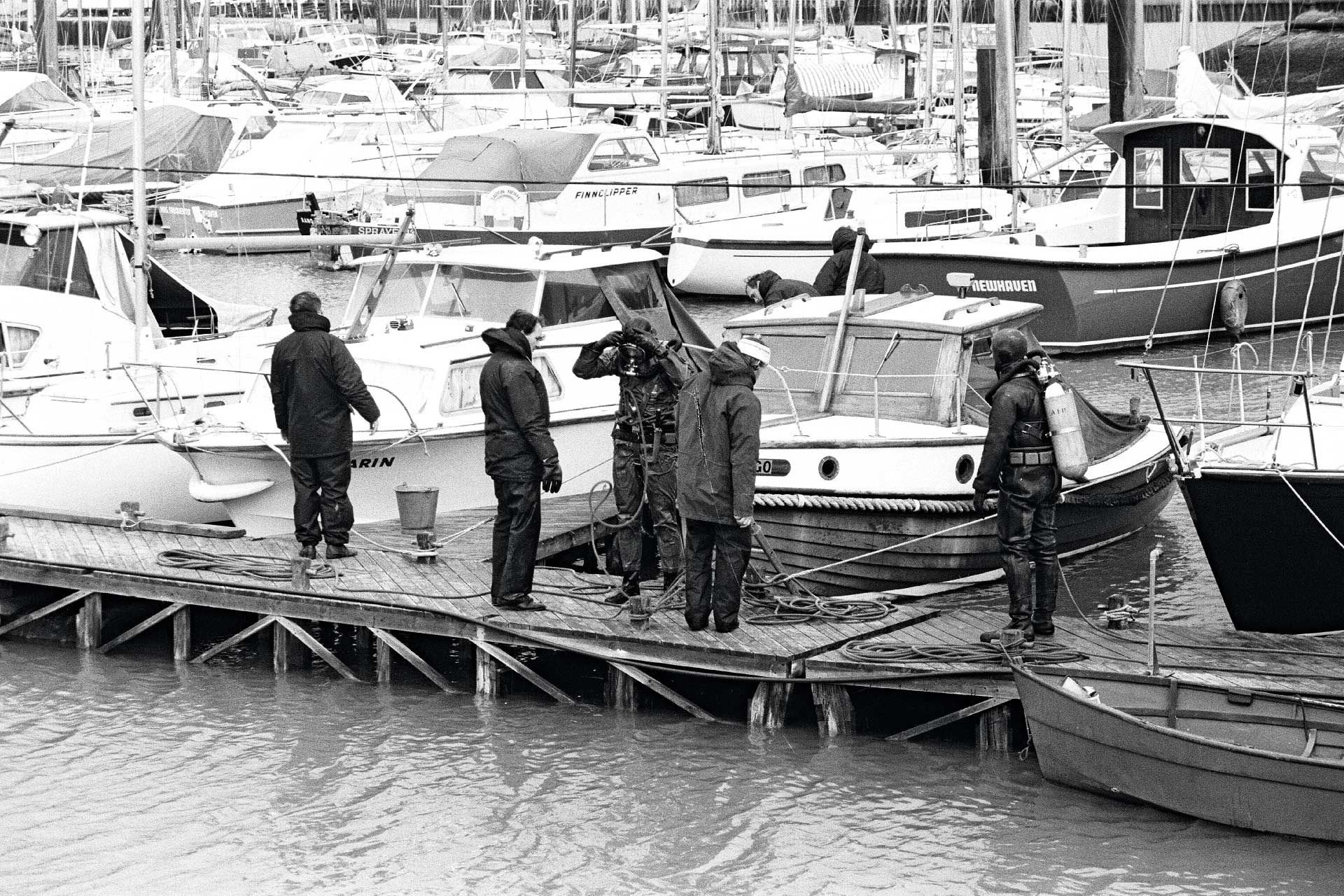

Veronica has no doubt that he committed suicide shortly afterwards, most probably by taking a France-bound ferry from the nearby port of Newhaven, where his car was later found, and jumping overboard.

Lady Lucan with Camilla, Frances and George. Eight years after the murder, the children went to live with relatives.

Others are less convinced. One popular theory is that after laying a false trail and lying low for a few days, the Earl was spirited out of Britain aboard a private jet arranged by his wealthy friends, who included tycoon Sir James Goldsmith and landowner John Aspinall.

“It wouldn’t have been very difficult to arrange,” says William Coles, “and Lucan’s pals were more than capable of doing it.”

Whatever happened to him, Lucan has left a tragic family legacy. Over the years, Veronica has fallen out with all three of her children, and no longer sees or speaks to them.

“I couldn’t give a hoot about them, frankly,” she once told me. “They are dreadful little people, nasty sneaks, the lot of them. People say, ‘Oh, but you’re their mother’, as though that’s the only thing that matters. Well, I won’t put up with them. They are my genetic spawn, if you want to put it that way, but I don’t even like to think about them as my children.”

Even so, the Lucans’ offspring have prospered under the shadow of their father’s infamy. Frances and Camilla are both successful barristers, while George, now the 8th Earl, a former merchant banker, married a wealthy Danish heiress, Anne-Sofie Foghsgaard.

They have rarely spoken of the night that changed their privileged young lives, although in public the Lucans maintain the united front that as their father was never brought to trial he should not be deemed guilty.

Last February, after winning a long legal battle to have his father declared officially dead, George said: “I am very relieved. It is a sensible verdict after all this time. It doesn’t mean anyone has escaped prosecution for the murder of Sandra Rivett, but a person must remain innocent until found guilty in a court of law.”

A poignant twist to the tale came with the revelation that Sandra Rivett also had a child – a son, Neil Berriman, whom she had given up for adoption at birth.

George Bingham, now the 8th earl of Lucan, lost a father.

Neil Berriman lost his birth mother.

Now 49 – the same age as George – he only discovered his true identity from old papers left after the death of his adoptive mother. While Neil agrees that Lord Lucan is probably dead, he originally opposed George’s application, complaining that Sandra, “the forgotten victim of this whole story”, was being denied justice.

He withdrew his objection after meeting with George, and the two men agreed the case should remain open.

“I lost a father and Neil lost a mother,” said the new Lord Lucan. “A beautiful young lady died, and we still do not know how it happened.”

Police searches where Lucan’s abandoned car was discovered weeks after the murder turned up nothing.

For Lady Lucan, working on her manuscript behind the drawn lace curtains of her home, nothing is forgotten.

There are reports of her being short of money, and selling off mementos of her life with the Earl. Not all of them, though. Above the mantelpiece hangs a slightly faded oil painting of her vanished husband, dressed in his ceremonial ermine robes, his lush moustache bristling, his aristocratic jawline firm.

Why keep such a prominent reminder of a man who tried to kill her?

“Well, it’s only decoration,” shrugs Veronica. “And it’s a rather good likeness. If I took it down, I’d have to find something to replace it with.”

Words: William Langley